Mike Aquilina’s new book gives us an object lesson in why Christianity matters

My maiden Aunt Norma wore Emeraude. A lifetime later, I can conjure up, at will, that obsolete scent — and instantly Norma is with me, and I am 9 again, doing some craft with her at her kitchen table.

In my dining room hangs a small cotton romper, matted on velvet, framed and glassed. My husband wore it as an infant. Several years ago his mother found it folded away and gave it to me. It’s my concrete link to abstract baby Jim, whom I love as much as I love the grown man. That’s why I protect and display it.

The memory of perfume, the piece of fabric: these things are holy to me. Spiritual. They fold time and space, enlarging the here and now. They matter.

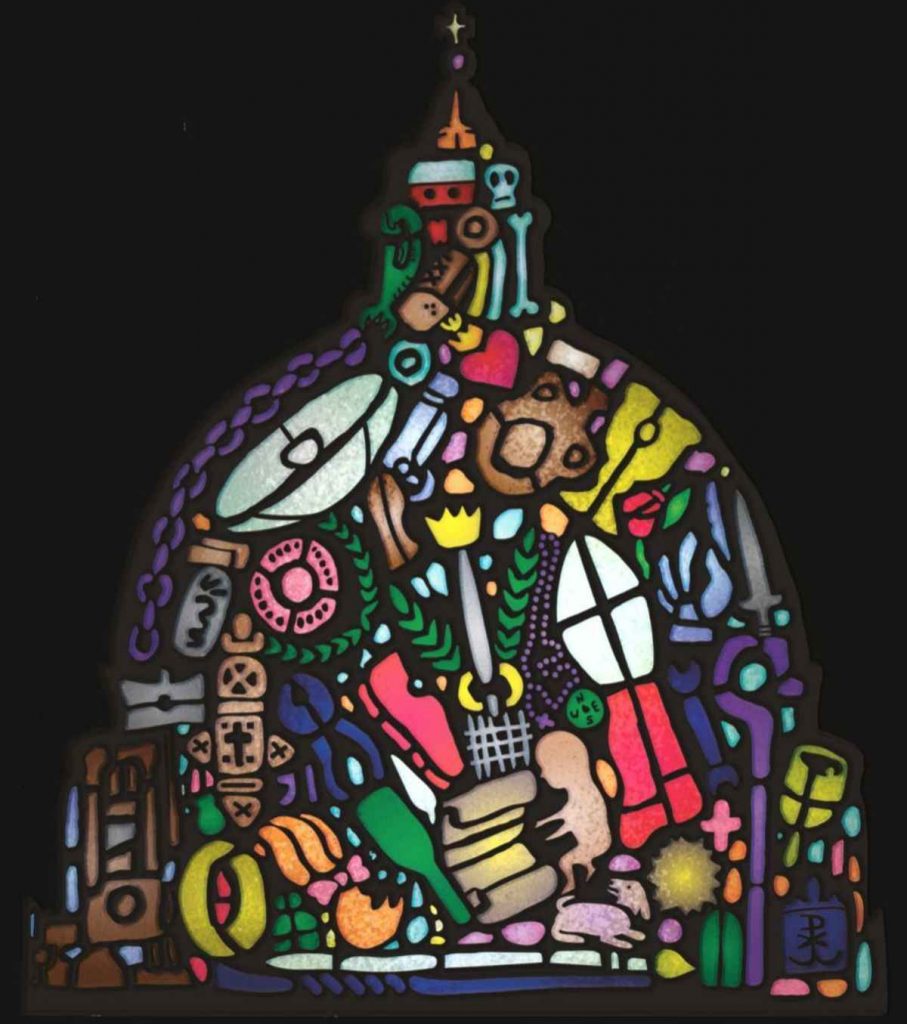

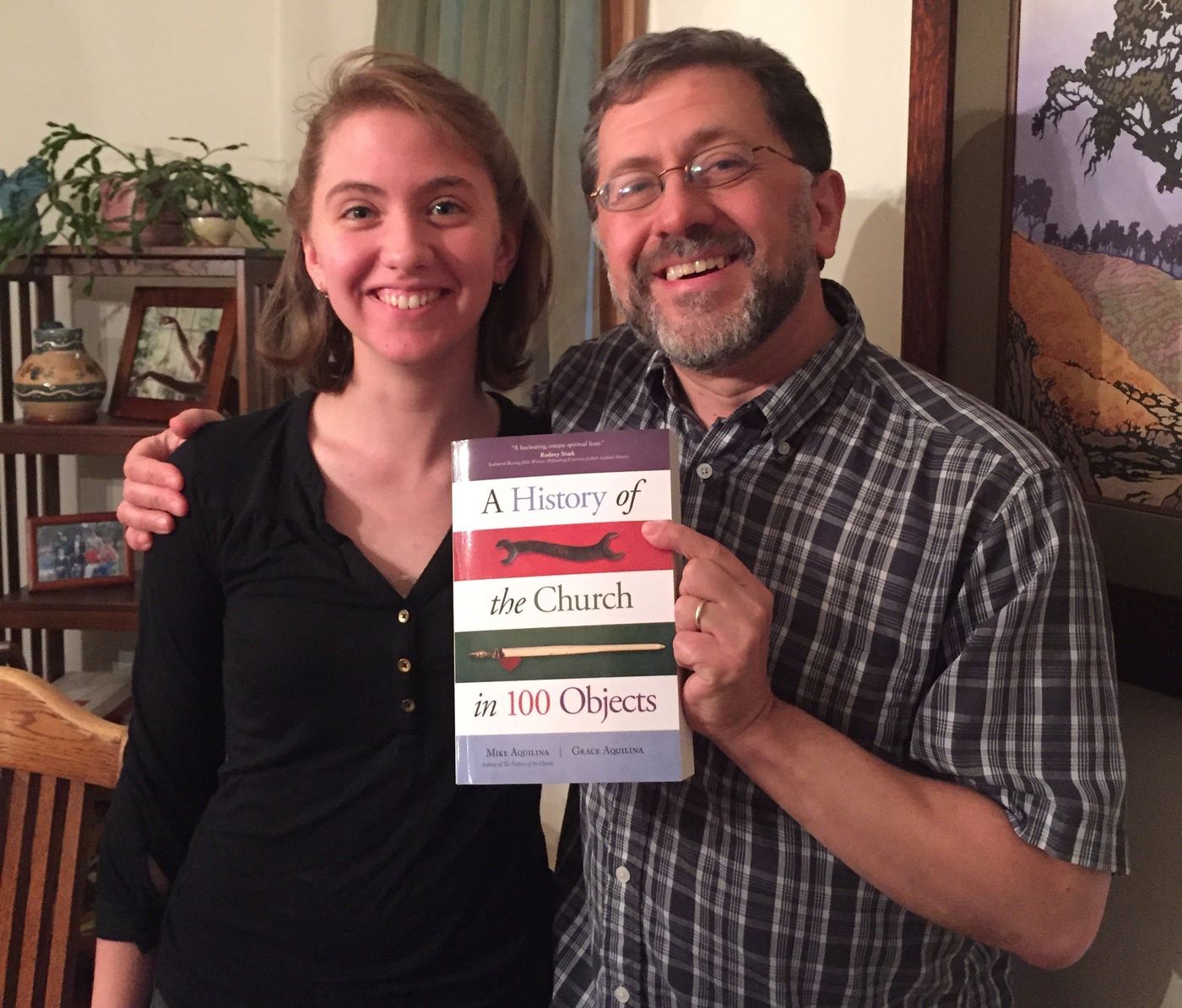

The belief that “matter matters” is what “A History of the Church in 100 Objects” (Ave Maria, $19) is about. Mike Aquilina and his daughter, Grace Aquilina, chose to take a close look at 100 existing objects whose stories help us stay attached to the past, present and future of the Church.

Mike Aquilina is a widely popular and respected host on Catholic television and author of many books on Catholic history, doctrine and devotion. He’s an enthusiastic explainer, never a show-off. His daughter, Grace Aquilina, is a freelance editor.

Together, they’ve created a book that’s approachable, informal, fun and beautifully clear.

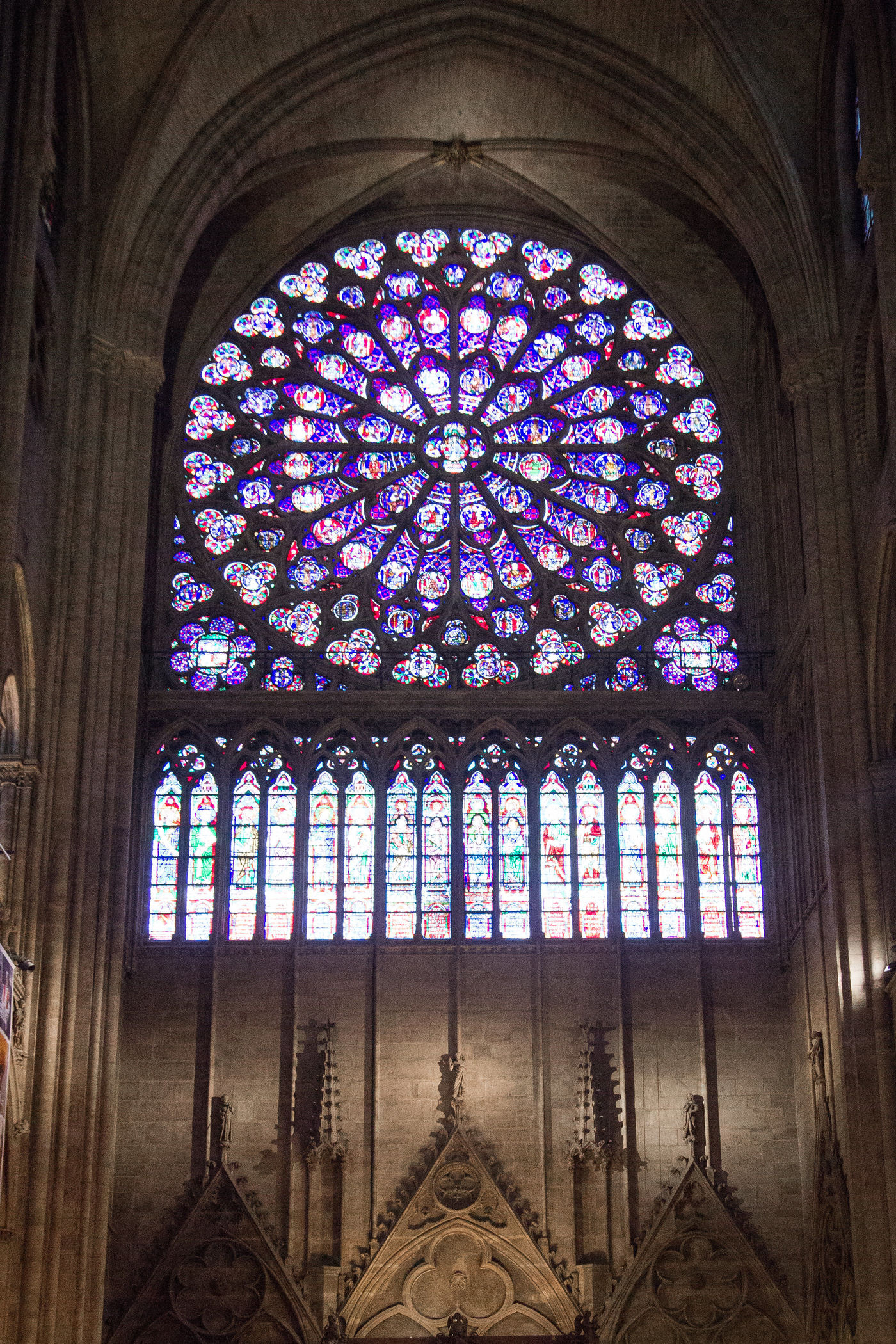

Each chapter begins with a color photograph of the object. Chapters are just two to three pages long, but are loaded with information and perspective. The authors seamlessly connect objects, eras and events. The flow of Church history, dense and mysterious as it is, makes perfect sense. Seminarians and sixth-graders alike can learn important things from this book.

The authors see objects as what they really are: wormholes. Shortcuts through time and space. The material objects transport us to wider, deeper understanding, if we’re interested in taking that ride.

The first chapter (they’re arranged chronologically) discusses the silver star in the Grotto of the Nativity in Bethlehem, marking the spot believed to be Jesus’ birthplace. How did early Christians know exactly where it was? How did the shrine change over the centuries, and why?

The hundredth chapter discusses modern pilgrim offerings at today’s shrines — and who the pilgrims are these days, and why the Church is a pilgrim Church.

In between, a Mexican martyr’s auto repair tools, a Byzantine wedding ring, a blunderbuss from Armenia and a pack of birth control pills link us directly, sensually, concretely, with the stories of the Church’s first 2,000 years.

How did dirt from the Holy Land come to Rome in the fourth century and wind up enshrined in a basilica? What is the purpose of the small hole in the wall of a Pittsburgh church? Why is Jesus completely naked in a Ravenna mosaic? Folding time and space, the objects reveal answers, enlarging our here and now.

The hundred objects were chosen subjectively. They could easily have been one hundred other objects. They could include your grandmother’s rosary. Your neighborhood mosque. An iPad. Because there’s either a solid or a dotted line between almost any object you could name and the Catholic Church. That’s how wide our influence has been.

The stories of the Church’s first 2,000 years are also the stories of the entire world’s past 2,000 years. The Church is a global village if ever there was such a thing.

“Ours is the church of ashes and incense, icons and statues, bread and wine, water and oil, incorrupt bodies, and bones encased in glass,” write the authors. “None of this is incidental to faith.”

God made matter, and saw that it was good. He made us out of matter. He became matter so that we could fall in love with him. The material world — including these hundred objects — is a love letter and a signpost for the human spirit.

“Salvation history is the story of God entering our world, sometimes with flash and dazzle, but most often through ordinary stuff amid the mess of centuries,” the authors write.

“And salvation history did not end with the close of the biblical narrative. It’s not even over yet. The end of the Bible opens out onto the beginning of our age.

“God makes himself known and accessible through material things, always accommodating himself to our condition. It is, after all, the condition he created for us — spiritual and material — and the condition he assumed for our salvation.”

In the eighth century, defending the use of religious icons, St. John of Damascus wrote: “The invisible things of God have been made visible through images [i.e., matter] since the creation of the world.”

Humans live in a sea of matter, most of which we don’t notice. To us, it’s like the air we breathe (which is, of course, matter). Matter is the only way to see spirit, and we usually forget to use it for that purpose.

But each of us also has at least one cherished example of matter: a joyful memory, a worn family heirloom, a beautifully made object, a dried wedding rose, a ticket stub. (A remembered perfume scent. A husband’s baby romper.)

We value these things because they connect us to our spirit. They ultimately refer back to God.

We journey to spirit through matter.

Our senses, our mind, our memory, and all the material things surrounding us: they’re what we have, and they’re not a wall, they’re a window. “A History of the Church in 100 Objects” reminds us of that.

Related reading: Talking about things visible and invisible

Jane Greer edited and published “Plains Poetry Journal” and is author of “Bathsheba on the Third Day.”