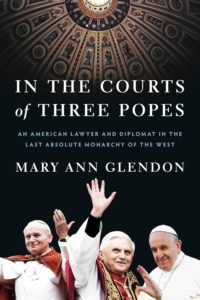

Mary Ann Glendon’s memoir, “In the Courts of Three Popes: An American Lawyer and Diplomat in the Last Absolute Monarchy of the West” (Image, $27), is actually much more than a memoir.

On one level, the book is a chronicle of her work for three popes. She represented the Holy See in Beijing in the critical U.N. Conference on Women under St. Pope John Paul II; was tapped to lead the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences by Pope Benedict XVI; and served on a working team to reform the structure of Vatican finances created by Pope Francis. Besides that, of course, she was the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See under President George W. Bush.

But on a deeper level, the book affords us something unique and unusual: the perspective of Glendon, a distinguished Harvard Law School professor, on some of the inner workings of the intricate Vatican bureaucracy.

In his blurb for the book’s back cover, Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York writes that Glendon’s book makes us all “insiders.” With all respect to the cardinal, that’s probably an exaggeration. But the fact remains: This book allows us “inside” one very observant and prudent person’s thoughtful reflection on her involvement with the ministry of St. Peter under three very different men, all called to what must be the most difficult and complicated job in the world.

It would be a mistake to see her memoir solely in terms of her analysis of some ecclesial and global issues, her intellectual grasp of theological and social doctrine, and her keen eye for the dynamics of committee work — all of which shine here. This rather short book is also a personal witness to her Catholic faith and her love for the Church.

I especially appreciated her analysis of how some Catholic public “faces” alternate between a turtle’s hunkering down into his shell and a chameleon’s changing with its environment to juggle the demands of faith in the context of a secular society. She was never a turtle nor a chameleon, especially in her valiant pro-life stance throughout a very public career.

I met Glendon briefly in Rome when I and a few priests had a chance to speak to her after a lecture at a Roman university. At the time, I was struck by her easygoing and totally unpretentious style. Here was a Harvard Law professor who remembered “Barry” (President Obama) as a nice young man she had in class. She was a friend of popes and pooh-bahs from around the world, but she seemed glad to share a few words with priests on a retread sabbatical course.

Glendon’s narrative connects several movingly told personal experiences: her experiences as a Catholic girl growing up among Protestant relatives; hints about her struggles as a single mother; her struggles as a woman in a field dominated by men; later in life, her grief for the love of her life, her Jewish husband Edward Lev, who died unexpectedly as she was enmeshed in an extremely complicated Vatican banking consultancy; and especially her loyal friendship with John Paul, as well as with Benedict. Reading them reminded me of Auden’s famous verses:

“Private faces in public places

Are wiser and nicer

Than public faces in private places.”

The book is an encounter with a private face in very public places. There are many enjoyable anecdotes mixed in, often involving figures we know only from the news. A few include Henry Kissinger, who opted to stay with other guests at the Casa Santa Marta (the guest house where Francis now lives) when visiting the Vatican to give a presentation, but was surprised its simple little apartments did not have room service; her friendship with Eunice Kennedy Shriver, whose birthday party was the occasion Glendon took to tell late Sen. Ted Kennedy that then-Sen. Joe Biden was giving her trouble about her nomination to the ambassadorship; Condoleezza Rice, “who did most of the talking” when they met; Sen. John McCain, who sat next to her at a White House dinner and did not know how to “talk Catholic;” President George W. Bush, who told Benedict he was grateful to meet him because “you are the greatest spiritual leader in the whole world;” and former Czech President Vaclav Havel, whose writings had inspired her and who had invited Glendon to speak at the prestigious Prague Forum 2000 about the future of Europe and the world.

My favorite excerpt from the book comes from the time she met with John Paul for the last time in 2004 — a miniature portrait of two incredible people:

“It was hard to keep back tears as I delivered my presidential address to him and then took my place at his side to introduce each participant. He leaned over, took my hands and said something to me, but his words were so blurred that I had to ask him to say it again. Very slowly, he repeated, “How’s the family?”

For anyone who wants to begin to understand what the Catholic Church is living through during the first part of the 21st century, “In the Courts of Three Popes” should be required reading. It made me wonder why, as seminarians, we never studied the various structures of ministry in the Vatican as we had learned about the different branches of the U.S. government in grade school.

Glendon’s expertise in comparative systems of law can serve as a short introduction to the actual government of the Church; all priests, especially seminarians, can profit from her sketch of the special challenges of administration faced by the Successor of Peter. And her short summary of some of the treasures of social doctrine would be instructive for any educated Catholic.

“In the Court of Three Popes” is a book like a message in a bottle to future historians of the Church in our time. We are lucky to read it before the waves of time take it away.