With rapid advances in artificial intelligence causing both fear and enthusiasm as it pushes the envelope of potential new frontiers in technological progress, a new app aims to show how AI can be used positively and serve as a tool for those curious about the Catholic Church.

Speaking to Crux, Matthew Sanders, Founder and CEO of international tech company Longbeard and the creator of Magisterium AI, said “There is a great deal of fear around AI, but there are many who feel it could be a powerful tool to share truth.”

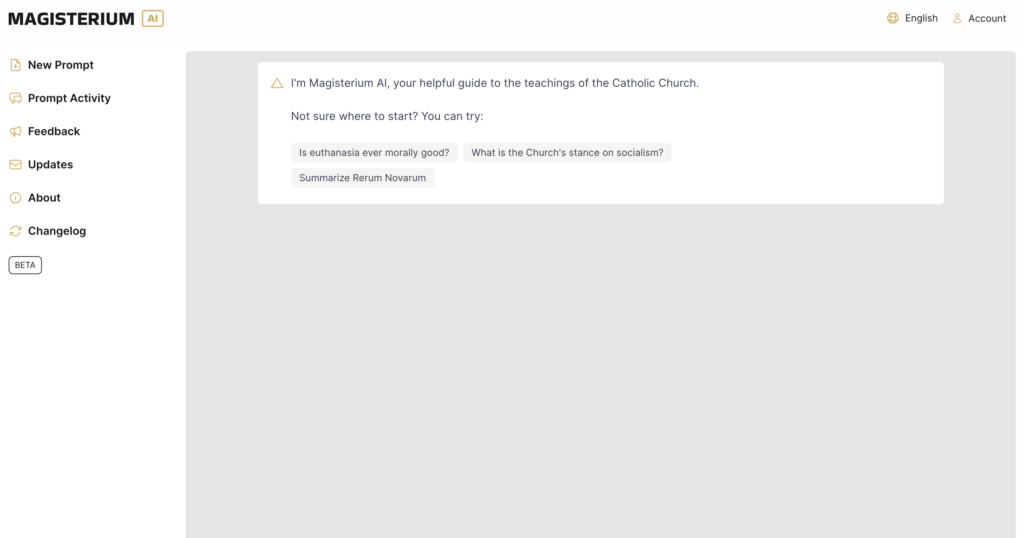

As an AI-based app currently in the beta phase, Magisterium AI “could be a game changer for the Church,” Sanders said.

The app is an AI that is trained by using a limited number of Church documents and which, similar to OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Bard, can be used to generate human-like text on specific content that could be used by anyone from Church scholars and academics, canon lawyers, students seeking well-sourced information to assist in studies, and anyone curious about Church teaching.

According to Sanders, the difference between Magisterium AI and ChatGPT is that “our AI is trained on a private database of only Church documents,” and therefore there is less chance the AI will “hallucinate,” which in this field means “make stuff up.”

“There are still kinks with the AI we’re working out, which is why we’re still in Beta,” he said, saying the AI will generate answers based on the magisterial documents it’s trained on and it also provides citations “so you know where its answers are generated from.”

“Its answers are not always perfect and it’s not a substitute for the authorities of the Church,” but it can be a very helpful tool, Sanders said.

The app, launched earlier this year, currently has around 2,580 magisterial documents in its knowledge database, and the list is growing.

Additionally, the app is able to generate responses in 10 languages: English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Dutch, Russian, Chinese, and Korean. It is being used in over 125 countries.

“Having worked in the Office of Spiritual Affairs at the Archdiocese of Toronto before founding Longbeard, I can tell you, a tool like this would have made my job a lot easier,” Sanders said, saying the app is “an enormous opportunity to make available the wisdom and knowledge contained in this unique to everyone.”

Jesuit Father David Nazar, rector of the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome, called the Orientale, serves as chair of Magisterium AI’s Scholarly Advisory committee, a growing network of universities and research institutes with unique Catholic sources that are not otherwise digitally available on the internet or in most parts of the world.

Speaking to Crux, Nazar praised the value that Magisterium AI could add to both the broader world of technology, and the church.

“The arrival of AI, with all its hype, is more similar than different from threshold discoveries that have come about every ten years or so for the century,” he said, noting that when television was gaining popularity in the 1950s and color TV quickly followed in the 1960s, there were warnings that “our minds would go soft, and our eyes would weaken from watching it too much.”

When the Beatles rose to fame, teachers said long hair would get in the eyes and cause blindness, and when DNA mapping gained prominence, it was thought that it would eliminate diseases and make everyone “smart and pretty,” just as the internet in its beginnings was touted as a source of infinite knowledge that would raise the standards of life even for the poor, Nazar said.

Yet the internet “also became an unlimited source of accessible pornography” and other nefarious activities, he said, saying, “AI suffers from the same kind of promise and doubt. It offers extraordinary opportunities for good and for mischief.”

“Since there’s no controlling people’s intentions, it is important for the sources of good, like religions, to be involved with this technology from the outset,” he said.

Noting that many people are nervous about where advances in AI might lead, Nazar said “evil finds its home in people, not things.” For those who fear it could lead to an end-of-the-world scenario, “AI is a gateway to the apocalypse about as much as television is the gateway to going blind,” he said.

Magisterium AI is currently partnering with the Orientale, which contains the largest library on Eastern Christianity, to digitize the library’s contents and add the documents it contains to the app’s database so the AI can train on them and make them available to users across the world.

Sanders said Magisterium AI plans to partner with other pontifical universities “in the near future.”

Father Philip Larrey, Chair of Logic and Epistemology at the Pontifical Lateran University in Rome and an advisor for the Magisterium AI product, said the app is more dependable than other AI services such as ChatGPT in terms of hallucinations and determining truth versus falsity.

Even though statistically the answers AI gives to a question have a very high likelihood of being true, if it does not have the correct answer, “it will also invent things in order to give you an answer.”

“In the trade that’s called ‘hallucinations’. Hallucinations are when the AI gives you an answer which is not true, it makes it up,” Larrey said, saying, “It’s a good sign that we’re still better than the AI, but that’s not going to be true much longer.”

Magisterium AI is a step ahead in terms of better guaranteeing true answers, because at this point, Sanders “defines what the information is that the AI is using.”

Larrey said he sees the app as mostly being used by scholars and academics, but said it is also of use to those curious about the Catholic Church and its rituals and teachings.

“Because it is rather technical in nature, I have a feeling it is going to be used primarily by academics and scholars in the Catholic field,” however, Larrey said he believes “it can be used by Catholics and non-Catholics as well,” such as those who want to know about the priestly vow of celibacy, or how a pope is elected.

“People have all kinds of questions like that, and they could use AI to answer it,” he said.

Larrey said that where he sees concern with AI is its potential to fall into the wrong hands or to be used by a malicious actor to wreak havoc or cause harm.

“People are a little bit wary, and Hollywood tells us that machines are going to take over the world. I love science fiction movies as well, but I don’t think that’s going to happen,” he said, saying that Magisterium AI is “a wonderful example” of how the technology “can be put to really good use.”

However, what Larrey said scares him the most about AI currently is that “it could be used by the wrong hands. A malevolent agent could get ahold of the AI and make it do stuff that is not good.”

The AI technology, which can change its own programs and set new goals for itself, could also autonomously decide to shut down gas stations, or release a contaminant into water, or worse, he said, saying, “the more power we give to the AI’s, the more risk there is that it could be used wrongly.”

To this end, Larrey said there is need for further regulations on the use of AI, voicing support for a proposal by Sam Altman, co-founder of Open AI and the creator of ChatGPT, for large AI platforms to obtain a government license.

He also voiced support for the Pontifical Academy for Life’s proposal to establish a clear ethical framework for the use of AI, which is outlined in its pact, “The Rome Call to AI Ethics,” which has been signed by representatives of several tech giants, including Microsoft and IBM.

The Rome Call to AI Ethics also proposed the establishment of international bodies regulating the cross-border use of AI, which is something Larrey said “would be very helpful, but I don’t think it’s very realistic.”

The reason for this, he said, is that the AI is funded by large tech platforms, and thus “it’s going to be up to the platforms” to regulate it, so “we need to talk to the people in charge of the platforms.”

In terms of developing the proper regulations for AI, Nazar said he believes that there are some starting principles, but “unfortunately we will have to wait for signs of its misuse in order to make appropriate norms and laws.”

“This is what we are witnessing today with social media: massive criticism, lawsuits for gathering personal data, and regulations against IT giants profiting from the use of personal data,” he said.

It is essential, he said, “that humans, especially the weak, come first. When they begin to suffer, there is something wrong that needs correction. So, governments and regulating agencies will have to be vigilant with AI as it grows.”

Calling Magisterium AI “a boon” for the students at the Orientale, Nazar said the app “will not write your thesis for you but will provide you with a summary and an impressive array of resources from a variety of languages on the topic of your interest.”

“This becomes an important study tool for students and research tool for professors,” he said, saying that as a small university, concerns about plagiarism are “minimal.”

“If, all of a sudden, a student were to present a thesis comparing creation myths of ancient Syriac and Coptic manuscripts written in high quality Italian replicating Dante’s triplet rhyme scheme, we would be suspicious. In sum, we know our students and their capabilities,” he said.

Nazar said that Magisterium AI “challenges our pedagogy. Professors must understand the possibilities of the tool and use it for their research, and they should encourage its intelligent use by the students.”

Noting that one impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was that it “enhanced our pedagogy and gave us new capabilities,” Nazar said that rather than being fearful of AI and its use in the Church, “We should embrace this technology and show that it can be used for good purposes.”