He’s the most popular figure of the Italian Renaissance, and the author of arguably the most famous — and mysterious — painting in the world, not to mention a brilliant inventor who was thinking about humanoid robots and helicopters years before basic amenities like electricity were discovered.

So now that helicopters and humanoid robots are a reality, can the mind of Leonardo da Vinci finally be rendered obsolete?

Worldwide tributes from Paris to New York and even Los Angeles all seem to be making the case that it can’t be. But one of them, the British Library in London’s “Leonardo: A Mind in Motion,” calls attention to two particular areas of Leonardo’s genius, and invites them to look in two places.

The first has to do with Leonardo’s ability to connect two fields that don’t talk to each other often, namely natural science and art. The second pertains to the relationship between spiritual “powers” and rational experience; in other words, Leonardo’s conception of the porous boundaries between material and spiritual realities.

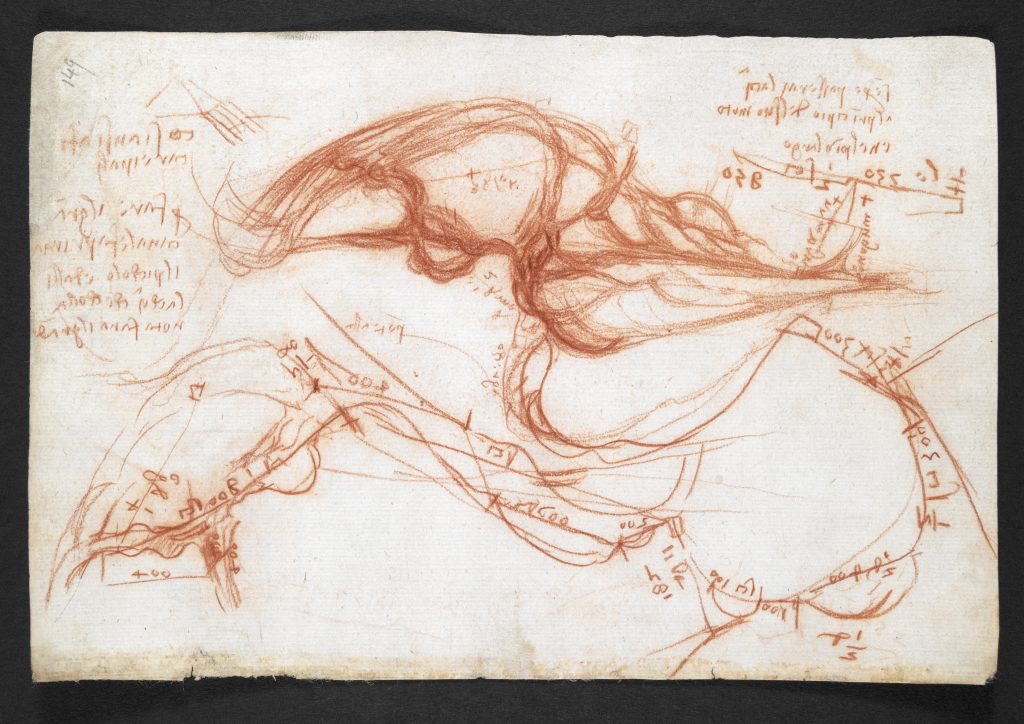

The exhibit brings together for the first time two of Leonardo’s private notebooks.

The first, the British Library’s Codex Arundel, is a major witness to the exceptional breadth of Leonardo’s interests: its contents range from mechanics, astronomy, optics, and geometry to engineering, architecture, and painting.

The other, the Codex Leicester, dates from Leonardo’s years as a hydraulic engineer in Milan. Now part of Bill Gates’ private collection, it is mainly devoted to the study of water and its movements, but also investigates questions relating to the structure and history of the earth and its transformations over time.

These notebooks have gotten far less press than Leonardo’s paintings. But together, they showcase Leonardo’s extraordinary ability as a draughtsman as well as giving us a glimpse of the inside of Leonardo’s mind.

Never published during the author’s life, they were meant for Leonardo’s eyes only. This is why, for example, they are written in Leonardo’s characteristic, nearly impossible to read “mirror writing,” written in the right-to-left script typical of lefthanders.

Though different in content and style, the two manuscripts are unified by Leonardo’s interest in the topic of motion. Leonardo saw motion everywhere, to the extent that he proclaimed that “motion was the cause of any life.”

The exhibit’s selection of sheets can be divided into five groups.

A first group of sheets concentrate on Leonardo as a student of nature, examining the course of river and erosion, and investigating the destructive powers of water.

A second and third group of items revolve around Leonardo’s interest in the greater world. Here we see Leonardo investigating such questions as the gravity and physical appearance of the moon, as well as contesting the traditional belief that fossils of marine animals found on the mountains can be used to prove the story of the Great Flood. Against this view, Leonardo held the correct (but then still unproven) position that mountainous areas had once lay on the bottom of the seas.

A fourth section looks more specifically at water and its movements. This section highlights Leonardo’s work as a hydraulic engineer and the practical aspects of his inquiry, but it also shows us Leonardo at his most creative. For example, in the sheet in which he lays out the design for an underwater breathing apparatus.

A final group of sheets looks at Leonardo’s study of mechanical and human movement. Here we see Leonardo comparing different machines for perpetual motion, a device that, once set in motion, can do work indefinitely without an energy source. Leonardo concluded correctly that such a machine is impossible, and compares its pursuers to the alchemists who seek to turn metals into gold.

Leonardo’s fascination with motion is also expressed in his Treatise on Painting (a copy of which is displayed in the exhibit), and elucidated in a number of studies of human subjects in motion. Leonardo was not just obsessed by motion in nature, but he brought motion to the center of his art.

He distinguished between two types of motion, which he called “motions of the body” and “motions of the soul.” In Leonardo’s view, the artist should strive to reveal the motions of the soul through his depiction of bodily posture and expression. As Leonardo himself remarked: “That figure is not praiseworthy if it does not express in gesture the passion of the spirit.”

In portraits, he broke with his contemporaries’ conventions of showing the sitter inert and in profile. His “Lady with an Ermine,” for instance, portrays a young woman caught in a dynamic expression, whose posture expresses the disposition of her soul.

The same correlation between psychological motions and physical motion is found in his sacred art. In his famous “The Last Supper,” Leonardo embarked on the greatest representation of human emotion ever to be attempted, in which every character displays, through a different bodily expression, the different movements of his soul.

And in the “Madonna of the Yarnwinder” he abandons the Florentine tradition of showing the child immobile and inert in the Virgin’s lap. To put it in the words of one of Leonardo’s contemporaries, Fra Pietro da Novellara, in this remarkable painting, “The child has placed his foot in the basket of yarns, and has grasped the yarnwinder, and stares attentively at the four spokes, which are in the form of a Cross, and as if he were longing for this Cross he smiles and grips it tightly, not wishing to yield to his mother, who appears to want to take it away from him.”

The expressions and movements of the figures uncover the thoughts of the painting’s protagonists, unfolding a theological discourse: The Child already longs to suffer for humanity, while the maternal heart of Mary moves instinctively to protect him.

The centrality of Leonardo’s theory of motion to his art is also crucial to the mysterious “Salvator Mundi” (sold in 2017 for $450 million). The painting portrays the half-length immobile figure of Christ with a crystal sphere in his hand, a detail meant to present him as a savior of the cosmos. Christ is motionless, but his gaze acts like a magnet, endowing him with a powerful force of attraction. This force of attraction, which Leonardo called a spiritual power and compares to a magnet, is capable of moving objects without being moved.

It’s that notion of spiritual power that allows us to appreciate an aspect of Leonardo’s mind that is most useful today. Not only is Leonardo no materialist — he does think that spiritual movements and powers exists, and that these are governed by similar laws as psychological and physical movements — but he does not posit, unlike most contemporary thinkers, a sharp divide between the material and the spiritual realms.

For Leonardo, spiritual motions are as real as the movements of objects, and can be grasped by our rational experience of reality. Even the magnetic power of Christ’s look, capable of attracting the hearts of humans, falls under the phenomena that can be grasped by our senses, and be made the subject of art.

That’s an idea that generations of Christian believers — from 1519 to today — would argue is far from obsolete.

Stefano Rebeggiani is an assistant professor of Classics at the University of Southern California.

Start your day with Always Forward, our award-winning e-newsletter. Get this smart, handpicked selection of the day’s top news, analysis, and opinion, delivered to your inbox. Sign up absolutely free today!