In “Birds of a Feather,” a wife and mother feels trapped by a secret. An abortion doctor’s mother would never have considered the option he offers. An Alzheimer’s sufferer feels judged and drives to his childhood home.

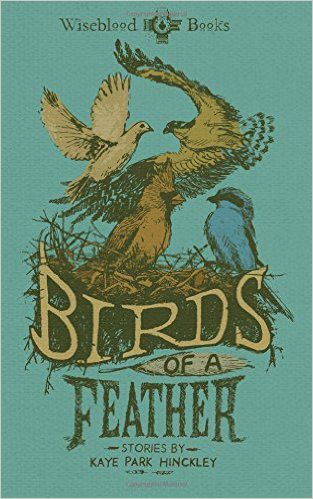

The birds in Kaye Park Hinckley’s short story collection, “Birds of a Feather,” all find themselves from flocks of Catholics. Their family members, or at least a shining few, believe in forgiveness, hope and redemption.

But it’s the sinners with whom we most sympathize. How can we not? Hinckley’s expert literary craftsmanship is matched by the drama of Judeo-Christian values confronting American relativism and egoism.

It’s Easter Sunday when the wife’s grandmother, on her deathbed, whispers, “We know the truth.”

The abortion doctor sees a newborn grasping for life then kills her.

The Alzheimer’s patient is frightened by the unforgiving eyes of that blonde woman, his wife. This fear leads his mind to relive his experience as a soldier crawling on his belly through enemy fire. In present day, he screams out loud — a military command to his fellow soldiers — scaring his daughter to tears.

Unlike his caretakers, the reader can see the interweaving of his past and present experiences. If you have ever stood at the bedside of a loved one with Alzheimer’s, Hinckley’s depiction helps to make sense of a beloved’s puzzling, and at times hurtful, outbursts.

For individuals struggling toward redemption, despite themselves, there are moments where the light, or, as the saying goes, the truth, hurts. “A patch of blue sky births an unblemished sun so holy in appearance I turn away.” Pain often accompanies being awoken to truth. “A ruthless streak of sunlight wakes me.”

Hinckley’s fallen humans are driving home. Many of them literally. All of them figuratively. Though some at the close of the story take “a procedural deviation from integrity,” we find ourselves hoping, alongside the practicing Catholic in the family, that they make it home.

Hinckley’s characters are alive. Their flaws and struggles create dramatic tension and lead us to reckon with the sinner and saint within. Throughout there is an uncanny presence of the Communion of Saints.

This is most explicit in “The Pleasure of Company: A Ghost Story.” The loving souls of two deceased grandparents tell us that their granddaughter, Julia, “is not alone …We are here … Ghosts from the past. Grandparents who love her.”

Each struggling character evokes a feeling of care within us. I will buy this book for all in my life on this side of the veil. It will be loved especially by the fiction aficionados and all the birds who have flown askew, losing the flock. “As one might lift a tiny, injured bird falling from a tree…”

As rare as the saints among us, a good short story is hard to find. But Hinckley’s collection, “Birds of a Feather,” remains with us with the power of an epic novel.