Amazon Prime’s new documentary on the late actor John Candy is subtitled “I Like Me,” a line taken from his famous monologue in “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles,” where he defends himself against the slings and arrows of a yuppie played by Steve Martin. What does it matter if the world hates him when his friends like him, and he likes himself?

The irony is that the entire world saw Candy as their friend. It was this inherent likability that elevated his good projects, floated his bad ones, and robs his own documentary of any sort of dramatic momentum. Everyone interviewed is unable or unwilling to say an ill word toward him (which as you get older, you realize means the same thing).

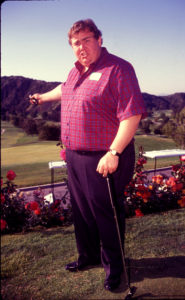

Candy was a member of that endangered species known as “The Everyman.” He was made in Toronto, made his name in Chicago, made his money in Los Angeles, and made his final days in Mexico. Each place mourned him as one of their own. I myself felt a proprietary claim to him, as in the film “Volunteers” he was proudly Tom Tuttle from Tacoma, Washington — my hometown.

Candy was one of God’s great characters, and as such his life sometimes read like unsubtle literature. He was born on Halloween and exactly five years to the date later, his father died of a heart attack at just 35, an event that convinced him he was already running on borrowed time. That made him not waste the years he had, but also not worry about the years he could have. There was something of a Greek tragedy to his passing from a heart attack at the tender age of 43. Perhaps hearing the prophecy made him fatalistically incapable of preventing it.

One of the risks of dying young is that those left behind will make you a saint at the expense of your humanity. The prevailing narrative of Candy conflates him far too much with his teddy bear “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles” character. But contrary to the archival footage, Candy wasn’t lit by beatific light. The man was from Canada, so he usually lived under no light at all. Part of being an Everyman is also just being a man, though this is no great sin: save for Guinefort, most of our saints were men too.

One of the more illuminating lines in the documentary comes from his widow, chuckling at the memory of how he was a “rebellious Catholic” when in reality, John was simply Catholic.

He partied, he drank, and, in his own words, “lived in sin” with his wife before marriage. But they were married at a Catholic church which, in a wonderful touch by the unsubtle author, was in the middle of construction. His faith may have been a work in progress, but it wasn’t a remodel. He tried, he failed, he didn’t make excuses, he tried again. He held grudges, especially about money owed to him, though it seems his fury was that getting stiffed limited his chances at generosity. One of his last acts on earth was a private donation to the Durango City Hospital, a city he had first stepped into just days before.

To those who knew from the screen, Candy symbolized the unfussed benevolence we all think we innately possess, if only reality and our personalities didn’t get in the way. But to those who knew him personally, his virtue was simple and manageable in the way most of us find impossible.

For example, the film shows how uniquely kind Candy was to crew members. His wasn’t the performative charity where the magnanimity feels insulting, letting you know just how far they’ve stooped to rub shoulders. Candy was a working man who never forgot it, seeing them as human beings and knowing that human beings liked pizza. His parties invited everyone, not just fellow actors in a similar tax bracket.

There was also charity in Candy’s restraint. One of the hardest parts of “I Like Me” is watching interviews where reporters, mistaking affability for familiarity, poke fun at his weight. Candy would laugh it off like a professional, but there is always a glimpse before the mask went on, where his mouth and his eyes weren’t sharing the joke. As the title says, Candy did like himself, but it's lonely when you feel like your only advocate.

The great tragedy of John Candy is that he saw changing his habits as a concession, that any concern for his health was just another dig. If he didn’t have self-esteem, he would at least cling to the self, preferring to go down with the ship than risk the cold, empty ocean.

My dad, a Candy fan, was man enough to tell me his eyes misted up as he watched this. I generously allowed him his sentiment, saving my teasing for a later day. Yet when it was my turn to watch, I stumbled at those same moments.

One of them was when Candy’s kids described themselves as detectives trying to learn about the father taken before they got to know him. Their remarks perfectly captured my own experience with my own late mother, who died during my childhood. There was the moment the 405 Freeway was shut down for his funeral procession (which began at St. Martin of Tours in Brentwood), a measure usually saved for visiting presidents or popes. Or near the very end, where they found Candy’s body on his hotel bed and his Gideon’s Bible fallen to the ground. They believe he was reading it.

No, I didn’t cry. But I did switch over to “Uncle Buck” before I risked doing so.