It may seem like a strange way to begin a discussion of Kanye West’s latest album, “Jesus Is King,” but here it goes: We might be talking too much about West’s latest album.

In the history of what Casey Kasem used to call the “pop-rock era,” a handful of conversions to one kind of Christianity or another have had what might be called headline-making ramifications: Cliff Richard’s (the mid-’60s), Al Green’s (the mid-’70s), Little Richard’s (in fits and starts from the late ’50s through the late ’70s), Bob Dylan’s (the late-’70s), Dion DiMucci’s (ditto), Alice Cooper’s (the mid-’80s), and Nina Hagen’s (the 2000s).

But even the concentric circles resulting from those big splashes, with the possible exception of Richard’s (whose faith-inspired philanthropy has made him a, if not the, face of Corporal Works of Mercy in the U.K.) and Dylan’s (whose Gospel-era “Trouble No More” box recently stirred up renewed interest), have to a large extent rippled out.

Curiously, of everyone on that list, it’s those whose pilgrimages, for whatever reasons, have been written and talked about the least — Little Richard’s, DiMucci’s, Cooper’s, and Hagen’s — whose publicly trackable behavior continuously places them on the faith-practicing radar.

Could it be that the more coverage a new Christian’s Christianity gets, the less likely it is that a new Christian will mature into an older one? Between how much a new believer ends up feeling rewarded by all the attention and how much the inevitable ebbing of that attention tempts him to think less of his Lord and Savior and more about how to get his next publicity fix?

If so, West is facing a steep uphill climb.

True, “over 1,000” people reportedly “rais[ed] their hands to accept Jesus as their Lord and Savior” in response to an “altar call” at West’s Nov. 3 Sunday service in Baton Rouge, and one wishes them well.

But even this good news should be understood in context: De-sacramentalized mass conversions are common in Evangelical Protestant circles.

And the bigger the numbers, the less the follow-up, meaning that there’s sometimes not much effort expended in finding out what percentage of people who “convert” in the middle of such emotionally charged atmospheres see their commitment through to the point of actually picking up their crosses and denying themselves daily (it’s notable that West’s most public declaration of his change in direction to date, for example, has taken place in a megachurch alongside Joel Osteen).

The Lord, as 1 Kings 19 makes clear, is not always in strong winds, earthquakes, or raging fires.

Frankly, the potency of what West’s doing now relies a lot on whether he’ll continue not only to talk his Jesus talk but also (and more importantly) to walk his Jesus walk.

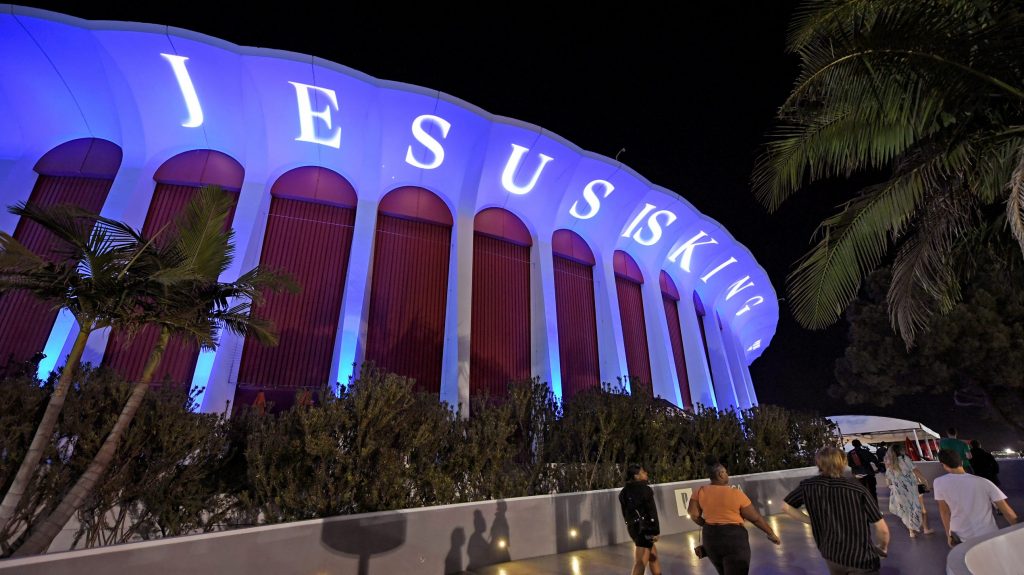

About that talk: At just over 27 minutes, “Jesus Is King” the album feels, strictly in terms of quantity, as anti-climactic as West’s 38-minute “Jesus Is King” IMAX film. Given the hype preceding both, one expected something, well, bigger. But, make no mistake, whether as music or as testimony, the album’s quality is no problem.

On the most basic level, it’s a reminder that rap can be good, clean, even effervescent, fun (something that listeners with fond memories of Grandmaster Flash, Run DMC, and DJ Jazzy Jeff and The Fresh Prince need not be told).

There’s a buoyancy to the “Jesus is King” flow of West and his featured guest rappers that seems to stem from the joy of discovering that there’s more to life than inventing new ways to deploy George Carlin’s “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” in celebration of the Seven Deadly Sins.

The flat-out jokes have the same effect. Not counting the mellow love song to Chick-fil-A restaurants (“Closed on Sunday”), which is hilarious on its face (even if West has some serious Sabbath-keeping on his mind) or “Follow God” (in which West’s father repeatedly shuts down arguments with his son by accusing him of not being “Christ-like”), “Jesus Is King” contains only two one-liners: “When I thought the Book of Job was a job, / the Devil had my soul” (“On God”), and “What if Eve made apple juice? / You gon’ do what Adam do / or say, ‘Baby, let’s put this back on the tree’?” (“Everything We Need”).

But they are funny, and, to quote G.K. Chesterton, “unless a man is in part a humorist, he is only in part a man.”

About that walk: One West fan has referred to “Jesus Is King” as “Jesus Walks” parts two through 12. “Jesus Walks,” for those not up on their hip-hop, was a double-platinum single from West’s 2004 debut, “The College Dropout.” In the song’s refrain, West raps, “God, show me the way ’cause the Devil’s tryin’ to break me down. / The only thing that I pray is that my feet don’t fail me now.”

West’s pastor, the Reverend Adam Tyson, has counseled, wisely, against cynically assuming that West’s feet will fail. Rather, Reverend Tyson insists (again wisely) believers should support and encourage their new brother.

But it’s not necessarily cynicism that makes observers wary of getting too pumped up about a celebrity convert. It was Jesus who, in the Parable of the Sower, cautioned his followers not to assume that every flowering of a seed would thrive.

The soil in some cases simply might be too rocky or too shallow to allow the word of God to thrive in it. In other cases, the sprouts get choked by thorns.

Of course, that parable isn’t meant to provide us with a schema by which we may assess the faith of others, but one by which we must assess our own. It’s a point that, judging from these lines from the “Jesus Is King” track “Hands On,” West understands: “I have a request, you see. / Don’t throw me up. Lay your hands on me. / Please, pray for me.”

Implicit in such a request is the hope that his soul’s soil will prove not rocky and shallow but rich and fertile and that the thorns, which (especially where celebrities are concerned) can be nettlesome in the extreme, will not prevail against whatever takes root and grows there.

So far, it must be said that West’s body of work since the mid 2000s shows an artist longing for true Christianity to overcome the shallow offerings of rap-star fame, even as he has since then battled addiction, dated a stripper, and, more recently, together with his wife, sadly employed the services of a surrogate mother to have two of their four children.

Still, in the case of West, there’s hope. Perhaps the track of “Jesus is King” that will enjoy the most long-term notoriety is his collaboration with Kenny G and rapper Pusha T, “Use This Gospel,” whose chorus goes:

“Use this gospel for protection / It’s a hard road to Heaven / We call on Your blessings / In the Father, we put our faith / King of the kingdom / Our demons are tremblin’ / Holy angels defendin’ / In the Father, we put our faith.”

Ultimately, it’s where West’s feet take him (and not his mouth, or the mouths of his supporters or detractors) that will determine whether his faith, in fact, has legs.

Let’s hope that this time, he’ll use the Gospel to help him get there.