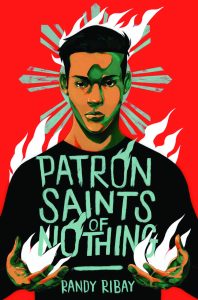

A sleepless night watching C-Span’s National Book Awards program led me to Randy Ribay’s “Patron Saints of Nothing” (Kokila, $13.74), a story about a Filipino-American high-schooler in Michigan who goes to the Philippines to investigate the death of his cousin.

Ribay didn’t win, but I ended up reading his book, which intrigued me from its dedication “to the hyphenated” to its unsatisfactory ending.

The novel is a kind of Huckleberry Finn story told by Tom Sawyer who is a kind of Filipino American modern-day Holden Caulfield (a Caulfield with a more extensive and R-rated vocabulary). Cousin “Jun” (for Junior) is the Huck Finn type and is three days younger than Jason “Jay” Reguero, his first cousin.

Jay’s mother is an American doctor, his father a nurse. When Jay visited the Philippines as a child, the two bonded quickly. They began a pen-pal correspondence hampered by Jun’s father’s refusal to allow the use of the internet. After a while, Jay was distracted and the cousins lost contact.

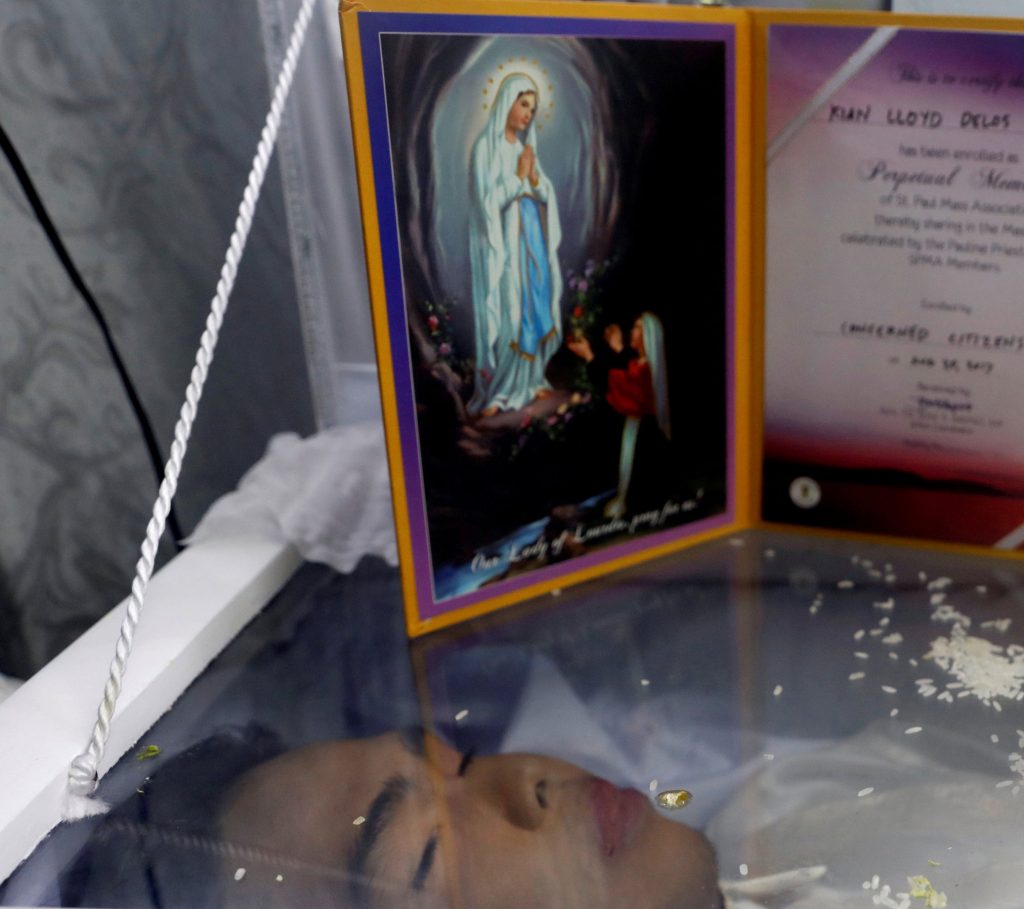

Then Jun is killed by vigilantes, encouraged by President Duterte, allegedly because he is a drug dealer. Grief brings about a crisis in Jay’s thoughts about himself, his family, and his identity as a Filipino-American (a “hyphenated” like those to whom the novel is dedicated).

The situation of the Philippines fills him with horror. What he learns about Duterte’s bloody repression of drug traffic shocks him: “It’s crazy and sad and shameful that all of this had been going on for the past three years, and I basically knew nothing about it.”

He feels alienated from his pot-smoking, atheistic, video-game buddy whose reaction to the news is, “No wonder you’re getting existential all of a sudden.” The friend also says, “I forget you’re a Filipino.” This leads to Jay’s conclusion: “It’s a sad thing when you map the borders of a friendship and find it’s a narrower country than expected.”

The first part of the novel is a poignant treatment of coming of age and wrestling with identity. Then Jay convinces his parents to let him go to the Philippines during his spring break of senior year.

Although they should know he is motivated by guilt, they give permission when he promises not to ask his uncle about Jun’s death. The uncle, Tito Maning, is an important police official and so Jay plans his own private investigation, presuming that there has been some kind of cover-up.

This turns the novel into an adventure story reminiscent of Anthony Horowitz’ Alex Rider books.

The plot bounces along on a series of revelations, some of which inspire and others appall him: his tyrannical uncle had disowned Jun, a kind of holy innocent; he then had gone to live with Jay’s lesbian aunt; then with a former prostitute, from whom he hid the fact that he had an anti-government web page and that he had turned to crystal meth, eventually selling it on the streets and being murdered for being a drug pusher.

Jun was, besides, a great reader of cutting edge books in various languages, and all of this before he was 18 years of age.

Interspersed with this thread of investigation are observations of modern Manila, caught between Third World squalor and First World aspirations. Jay goes to an ice-skating rink in sweltering Manila and the power goes off. The air-conditioning of his uncle’s car and house is also a symbol of the contrasts of Philippine culture.

Hampered by his lack of Tagalog, Jay nevertheless discovers some interesting facts about history and culture, colonialism and nationalism, and the current politics of atheist strongman Duterte, his uncle’s hero, and the world’s indifference to the corruption and injustice. Duterte’s opposition to the Catholics is not mentioned, but the novel shows a thumbnail sketch of a foreign society in stress, which is more than can be said of most fiction for young people.

I found the novel informative in details. Like the Salvadorans I worked with for 20 years, Filipinos point to people and things with their lips; they also love chicharrón; there are more than 170 languages and dialects spoken on the islands; American involvement in their history is deeper than most of us would be aware, etc.

In the midst of Jay’s investigation, we are given a kind of Cook’s tour of Manila, with mention of monuments and museums, parks and malls.

The gay trope in a young adult novel is probably de rigueur these days, but there seems to be an embarras de richesses in this regard that betrays. Jay’s brother Chris, his cousin Grace, and his aunt are all in homosexual relationships. Jay fervently wishes his aunt could “marry” her partner.

His own hetero credentials are established, however, by his crush on a beautiful African American student at his lily-white suburban high school. The girl refused his prom invitation, but the sister of his cousin Grace’s “friend” sparks his interest as they investigate Jun’s death. The ideological component behind “The Patron Saint of Nothing” seems as creative as painting by numbers.

That title is what made me want to read the novel, but is only tangential to its plot. I was interested in what Ribay reflects of contemporary Filipino attitudes toward religion. I have no idea of how representative he is.

His hero Jay has lost his Catholic religion and various anti-clerical sentiments are mouthed by him and Jun’s sister Grace. A beautiful church was built “on the backs of the poor,” priests hide their corruption by their power, etc. Duterte is praised by the police chief for passing out contraceptive pills as if this is an unarguable point in his favor.

The reflex prejudice against the Church which is found in so many “creative” sectors of society makes me think of St. John Henry Newman’s comment about the Anglican church of his day: “The talent is against us.”

Jay has a certain ambivalence about religion, however, as does his creator. Jay’s family has lost their religion: his brother is a gay scientist and his sister a drug-using college student. His mother and father no longer go to church, although Jay admits to almost missing going to Mass.

Nevertheless, his Tito Danilo is a priest who is shown more or less favorably. He reveals the sordid ending of Jun’s life but also leads a cathartic prayer service for his nephew that reunites the family. His words at the service are what suggest the title of the novel.

The attitudes reflected in the novel made me wonder how hyphenated first- and second-generation Filipino Americans are keeping the faith.

The great Catholic American novelist Walker Percy said novelists are like the parakeets in the mines. The birds died if there was not enough oxygen, warning the miners of danger. Is Ribay such a parakeet in terms of Filipino American religiosity? Is his fiction an early warning sign?

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has many projects about issues in contemporary society, some of which might be said to produce more heat than light. Is anyone doing research on the religious practice and formation of the hyphenated ethnics besides the Hispanics?

What about the Asian Catholics from the Philippines, Vietnam, and Korea — are their young people hanging on? That is the concern about the Hispanics, reflected in the Quinto Encuentro, but is there any data on other groups? Immigration and assimilation take more of a toll on Catholic youth now that the Church’s education system has drastically changed shape.

Are the hyphenated Catholic Americans losing their religion? Shouldn’t someone be watching?