Art restoration is a tricky business.

Taking a brush, sponge, or scalpel to a masterpiece requires remarkably steady nerves, not to mention technical expertise. As restorers repair the ravages of neglect or damage, they are dogged by the concern for fidelity to the original, responsibility toward posterity, and the nagging fear of complaints from the peanut gallery that the work has been “irreparably damaged” by incompetence.

A spate of disastrous restorations in Spain has increased the stakes for the beleaguered professional restorer, as amateurs have created an art form that appears to be taking on a life of its own.

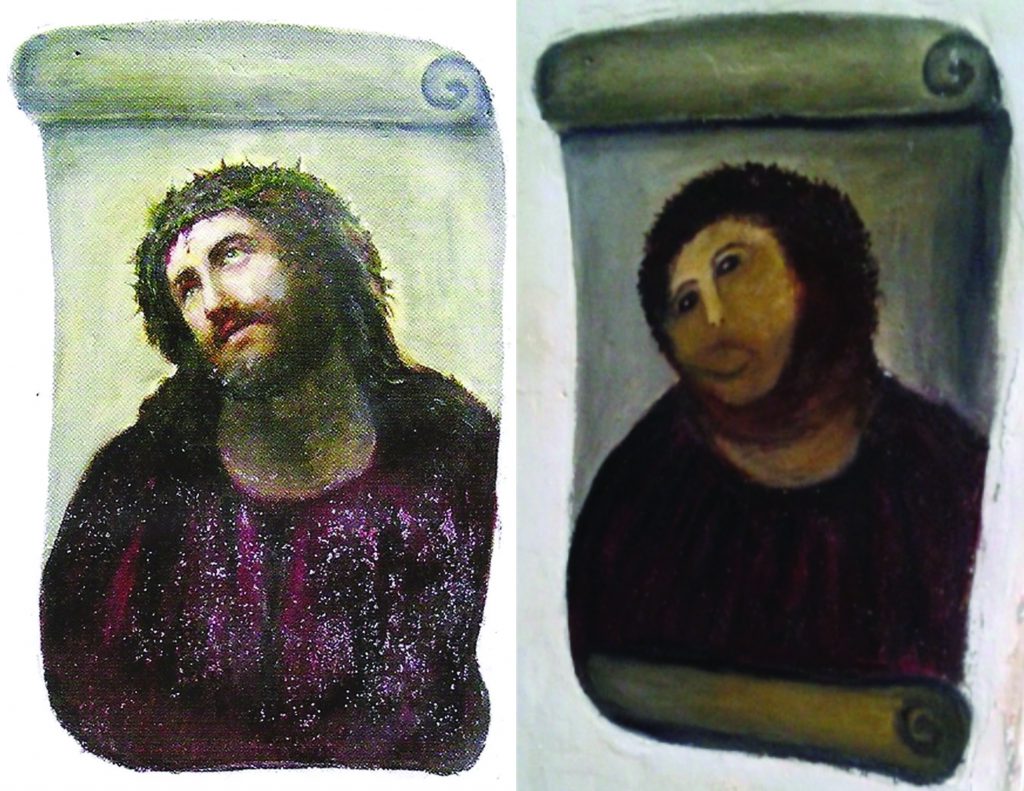

Known as the “Chapucismo” movement, meaning a sloppy cob job, it was started in 2012 by the restoration of an “Ecce Homo” (“Behold the Man”) in Borja, Spain, when an elderly parishioner, worried that a 1910 fresco by Elías García Martínez was falling into ruin, attempted to restore the work herself.

The result, unrecognizable from the original, was dubbed “Ecce Mono” (“Behold the Monkey”), launching a tourist sensation with more reproductions of the “restored” version sold than the original.

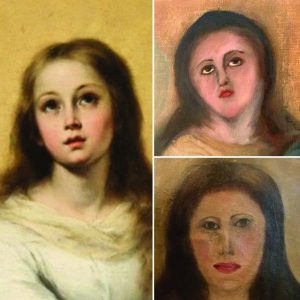

Other notable examples of the trend include the 2018 repainting of a 16th-century “St. George and the Dragon” wooden statue, now known as “Tintin” for his resemblance to the famous Belgian cartoon sleuth. Or the 2020 restoration that turned a copy of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s “The Immaculate Conception” into what now looks like a Modigliani painting on hallucinogens.

The most recent work to join this rogue’s gallery of ruined art was a decorative stucco of a young woman on a bank building in the Spanish city of Palencia, now deformed into what pundits are calling “Mr. Potato Head.”

The term “Chapucismo movement” was coined by Spanish comedian Dani Mateo. Tongue in cheek, he extolled its characteristics of “color without criteria and nonexistent perspective … yet filled with emotion, sentiment and Botox — because of all the retouching.” He interprets the “Chapucismo” manifesto as “Who needs a restorer? I can fix this in five minutes.”

While expertise in the Chapucistas’ body of work has become a popular form of internet entertainment, especially during the coronavirus pandemic, there are many who are not laughing.

ACRE, the association of professional restorers in Spain, has been active on Twitter pointing out the irresponsibility of allowing amateurs to work on priceless pieces of Spanish heritage. Having spent five years in training, learning theory as well as practice, they are appalled to see the good name of Spanish restorers ruined by a few dilettantes.

The solution, according to ACRE, would be increased regulation to ensure that restoration projects only fall to trained professionals.

As great art requires a great patron, however, bad restorations are often made possible by negligent owners. Each one of these notorious restorations was undertaken with the acquiescence of the people responsible for the work.

In the case of Cecilia Giménez’s efforts on the “Ecce Homo,” the octogenarian claimed that she acted on her own initiative, but in full view of the clergy in charge of the church.

The private owner of “The Immaculate Conception” was apparently trying to save money when he hired a local furniture restorer — instead of a trained restorer — to fix the painting for an alleged 1,200 euro.

The priest in the Spanish town of Estella who hired a “crafts group” to repair the St. George statue may have been trying to support locals as well as conserve funds, but the “unrestoration” proved quite costly at 34,000 euro.

The author of “Mr. Potato Head” remains at large, with investigations pending to discover how the restoration was commissioned. One could argue that the real proponents of “Chapucismo” are the owners, not the executors.

Art is often deemed “priceless,” underscoring the happy convergence of genius, skill, and material to produce a unique work. Yet sadly, the stewards who are entrusted with the care of these objects sometimes look for conservation bargains to the detriment of their precious charges.

Great art costs money, as the builders of Chartres or the sponsors of timeless paintings would readily acknowledge. And when it comes to great art, the price tag can be remarkably high.

St. Pope John Paul II was stymied at how to raise the $10 million needed to clean the Sistine Chapel in 1980, and was only able to get the ball rolling by selling the photographic rights to Nippon Television Company for $4.2 million.

The attention drawn by the project brought about the creation of the Patrons of the Arts of the Vatican Museums, an association of benefactors who donate exclusively to the task of restoring the art in the papal collections.

As a result, the Vatican Museums leads the world in art restoration for its extensive diagnostic testing, innovative approaches, ecological concern, and conservation integrity.

So far, the 21st century has shown itself to be unkind to art. There’s been rampant vandalism of churches and historic monuments, toppling of statues, and a rejection of the magnificent parade of masterpieces of western art under the auspices of political correctness.

Perhaps the “Ecce Mono” best sums up our present era, where people take more delight in laughing at a damaged image of Christ than in him. Indeed, “Chapucismo” may be the perfect movement to represent our age — sloppy in stewardship as well as faith.

If so, the remedy may also be the same. A recovery of appreciation for the treasures of the Christian faith may well lead to a reevaluation of the rich history and legacy of Christian art.