When a Harvard professor needed fast cash to test the date of a controversial document that made a startling claim about Jesus, she knew where to go: “Funding for the carbon-14 testing was generously provided by a gift from Tricia Nichols,” noted Karen King of Harvard Divinity School in her 2014 article for Harvard Theological Review.

But who was Tricia Nichols? The journalist Ariel Sabar wanted to find out. He’d been covering King even before she had announced in 2012 the discovery of a piece of papyrus that quoted Jesus as referring to “my wife.”

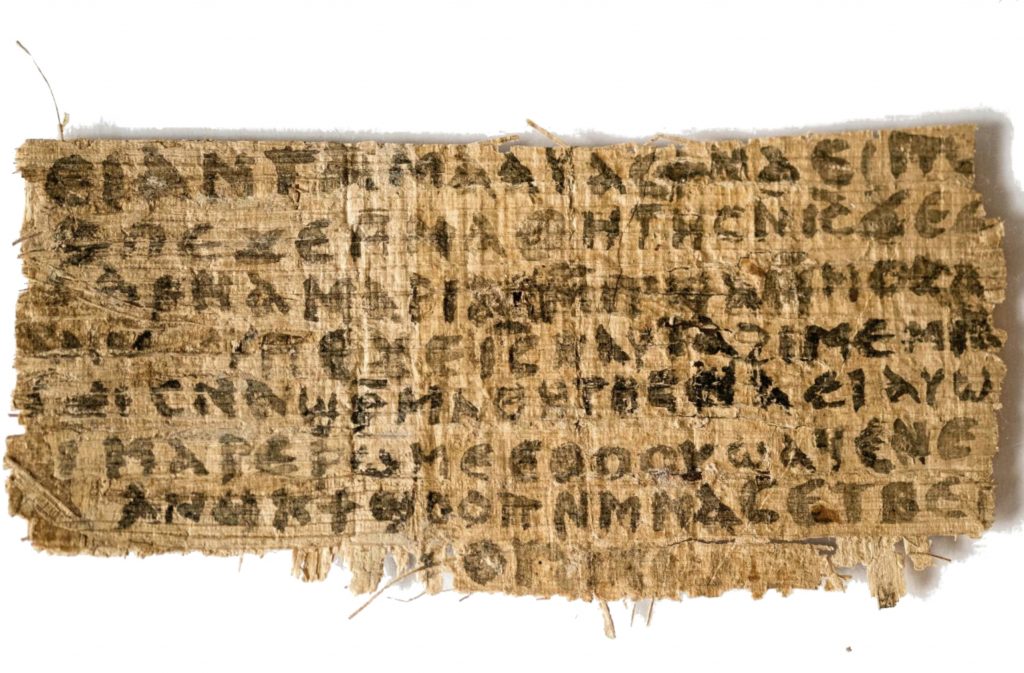

Written in Coptic, an ancient Egyptian language that uses Greek letters, the fragment is smaller than a business card and contains eight lines of broken text. It was supposedly part of a much larger manuscript, now lost. King gave the scrap a provocative title: “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.” If nothing else, the name was a brilliant bit of branding: She made front-page news around the world.

Yet it was also a fragment of her imagination. The once-celebrated document is a forgery, as many scholars suspected from the start and as Sabar shows conclusively in his outstanding book of investigative journalism, “Veritas: A Harvard Professor, a Con Man, and the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” (Penguin Random House, $29.95).

Sabar has written a true-crime tale that reads like a reverse “Da Vinci Code”: Whereas Dan Brown’s notorious novel described the fictional exploits of a Harvard professor who battles Catholic reactionaries and learns that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were husband and wife, Sabar’s work of nonfiction tells how a Harvard scholar was duped into believing the false claims of a phony document because they appealed to her professional ambitions and ideological fantasies. (I podcasted with Sabar here.)

Tricia Nichols played a minor but revealing role in the drama. She donated $5,000 to Harvard Divinity School to pay for the radiocarbon test of King’s so-called gospel. Although King cited Nichols in her academic article, the Harvard scholar refused to answer any of Sabar’s questions about her patron. A determined Sabar searched for Nichols on his own: “It was a common enough name, but after some false starts I found her.”

So who is the person who underwrote a key study of a bogus text that makes explosive claims about Jesus? “The widow of a medical testing magnate, Nichols is a Southern California philanthropist and abortion-rights activist with no record of having ever before donated to Harvard Divinity School.”

Moreover, notes Sabar, the gift to Harvard via Nichols’ Cirila Fund “coincided with Nichols’ public criticism of a hospital that banned elective abortions after affiliating with a Catholic health system.” Sabar found a letter to the editor written by Nichols and published in the Daily Pilot, an Orange County newspaper: “The Catholic Church’s historical position, based on the likes of St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, is that women were created to live under the subjugation of men,” wrote Nichols in 2013.

“This assumption is surpassed only by the sanctimony of the Covenant Health Network. Central to its doctrine is that women are to be denied self-determination in their healthcare decisions, and male administrators are granted the audacious right to select which legal reproductive procedures they’ll make available.”

After quoting these passages, Sabar observes dryly: “That the generous funder of a key test had a contemporaneous political stake in a specific test result — one that challenged ‘the Catholic Church’s historical position’ — was never publicly disclosed.”

The dating test, by the way, showed that the papyrus that enamored King is indeed old. The forged text it bears, however, is the product of modern chicanery. Although King and other scholars fell for it, several experts in Coptic regarded the script as sloppy and spotted grammatical problems.

Some of them were distinguished professors, but in an interesting and even inspiring detail, a couple of influential skeptics were self-trained scholars who worked from their homes and lacked institutional support.

By following the money, Sabar uncovers a small episode in what is a much bigger story about a fraud that involves everything from the priest-abuse scandal and online pornography to academic self-dealing and the perils of postmodern relativism.

At its heart, though, Sabar’s excellent book is about the quest for truth. That’s why he called it “Veritas,” which also happens to be the Latin word that appears on the seal of Harvard University.