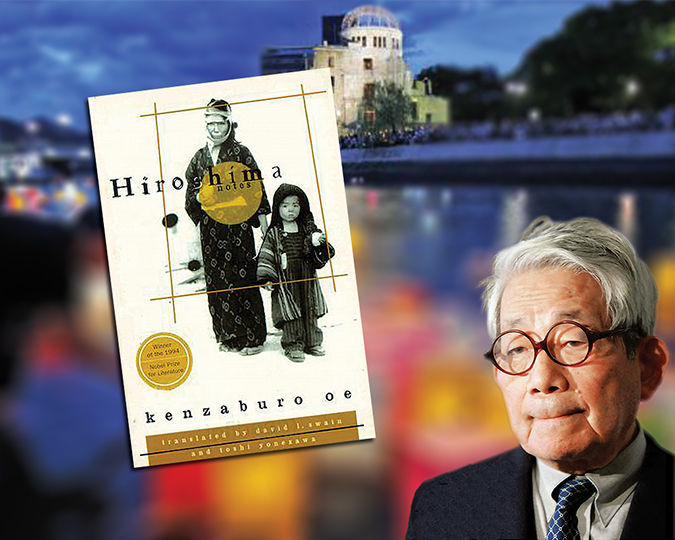

In 1994, the Japanese writer Kenzabur≈ç ≈åe was awarded the Nobel Laureate for creating an “an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today.”

Back in 1963, ≈åe’s wife, Yukari, was pregnant. Doctors advised the couple that the baby would be severely developmentally and physically disabled, and urged them to abort. They chose otherwise, and their son Hikari was born. He was visually impaired, epileptic and possibly autistic. He did not speak.

Hikari's awakening began when he heard a bird in the woods. From an interview with Ōe:

“Until my son was 4 or 5 years old, he didn’t do anything to communicate with us. We thought that he cannot have any sense of the family. So he looked very, very isolated — a pebble in the grass. But one day, he was interested in the voice of a bird from the radio. So I bought disks of the wild birds of Japan.… We continued to listen to that tape for three years….

“In the summer when he was 6 years old, I went to our mountain house, and while my wife was cleaning our small house, I was in the small forest with my son on my shoulders. Nearby there is a small lake. A bird sang, [one of a pair]. Suddenly a clear, flat voice said, ‘It is a water rail.’ Then I shook. Utter silence in the forest. We were silent for five minutes and I prayed for something, there on my head. I prayed, ‘Please, the next voice of that bird and please next the remarks of my son, if that was not my phantom or dream.’ Then after five minutes, the wife of that bird sang. Then my son said, ‘It’s a water rail.’ Then I returned to my house with my son and talked to my wife.”

The ≈åes went on to have two more children, and the most helpless, the least efficient, became the unlikely “star” around whom the family constellated. Kenzabur≈ç ≈åe went on to write novels, essays and memoirs around the central theme of his disabled son — this great fact, this “personal matter” — that has shaped his work, thought, and life.

Ōe has another abiding concern: the events of August, 1945.

“People say that I’ve been writing about the same things over and over again ever since — my son Hikari and Hiroshima…. I read a lot of literature, I think about a lot of things, but at the base of it all is Hikari and Hiroshima.”

For the follower of Christ, the connection is instant, and complete. Just as we de-humanize the “defective” or unwanted child, so we de-humanize the “enemy” toward whom we aim atomic bombs, drone strikes and shock and awe military campaigns. In both cases, we close our eyes. In both cases, we convince ourselves that the “surgical strike” is actually compassionate. In both cases, we are assured by secular culture that destroying another human being is reasonable, sane and empowering.

≈åe interviewed hundreds of atomic bomb survivors for his book “Hiroshima Notes.” In it, he reminds us that the view from the air and the ground are very different. He writes:

“In Hiroshima at dawn on A-bomb Memorial Day, I have often seen many women standing silently, with deep, dark, fearful eyes, at the Memorial Cenotaph and similar places. On such occasions, I recalled some lines by the Russian poet [Yevgeny] Yevtushenko (as translated here from the Japanese version by Sotokichi Kusaka):

“Her motionless eyes had no expression;

Yet there was something there, sorrow

or agony,

Inexpressible,

but something terrible.”

As Dostoevsky said, “Love in reality is a harsh and dreadful thing compared to love in dreams.” It so happens that Hikari ≈åe has an uncanny facility for music and is now a successful classical composer. But ≈åe never sentimentalizes Hikari. He has written of Hikari's abysmal oral hygeine, his immovable bulk, the years of laboriously accompanying him to the special school via bus and train and then making the same trip again in the afternoon to fetch him back: hours that could have been spent writing, producing. To sentimentalize children limits our compassion to those who are cute and controllable.

Only in acknowledging that a developmentally disabled child — any child — is difficult can we begin to extend our love to everyone. Only in acknowledging that loving our enemy is impossible, unaided, can we begin to see that God took on human flesh to help us. Only in contemplating a father’s love for his son can we begin to understand the magnitude of the sacrifice.

“If there is one area through which I encounter the transcendental, it is my life with Hikari during the past 44 years…. Every night, I wake Hikari to go to the bathroom. When he returns to bed for some reason he cannot put a blanket on himself so I put a blanket on him. Taking Hikari to the bathroom is a ritual and has for me a religious tone. Then I have a nightcap and go to bed.”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.