In 2019, on his return flight home from a papal trip to Thailand and Japan, Pope Francis was asked a question by Father Makoto Yamamoto, a parish priest in Fukuoka, Japan: “Does society and the Church in the West have something to learn from society and Church in the East?”

“It is very helpful for Western society — always too rushed — to learn some contemplation, to stop. To look at things, even poetically,” Francis responded. “I think that the West lacks a bit of poetry.”

Although Francis went on to explain that a poetic approach to life included “gratuitousness, seeking one’s own perfection in fasting, in penance,” his answer begged further development. Was he using poetically as a mere adjective, to describe a more contemplative life?

Now, five years later, Francis provides us with an answer.

On Aug. 4, the pope released a letter titled “On the Role of Literature in Formation.” His timing is apt. Reading, Francis argues, can be a healthy escape from “our present unremitting exposure to social media, mobile phones and other devices.” Literature removes us from dangerous digital attention and instead promotes reflection and conversation.

The letter’s style is gently meandering, and his tone is open and optimistic. But his conclusions are clear: “Literature can greatly stimulate the free and humble exercise of our use of reason, a fruitful recognition of the variety of human languages, a broadening of our human sensibilities, and finally, a great spiritual openness to hearing the Voice that speaks through many voices.”

Francis originally intended the letter to focus on the role of literature in priestly formation. Shadows of that original intention remain in the final letter, and make it feel like three narratives in one: an appreciation for the positive effects of reading literature, the benefits of literary study for seminarians, and how priests can be like poets and artists.

“In our reading, we are enriched by what we receive from the author and this allows us in turn to grow inwardly, so that each new work we read will renew and expand our worldview,” he writes. Close, sustained reading is a form of attention. Not merely “entertainment,” literature “engages our concrete existence, with its innate tensions, desires and meaningful experiences.”

Francis quotes Gaudium et Spes (“Joy and Hope”) in affirming that “literature and art … seek to penetrate our nature” and “throw light on our suffering and joy, our needs and potentialities.” Literature cultivates our emotional imagination; we “become more sensitive to the experiences of others,” and can “sympathize with the struggles and desires” of those like and unlike us: “the fruit seller, the prostitute, the orphaned child, the bricklayer’s wife.”

Arguments in favor of reading are nothing new, of course. But the successor of Peter inviting Catholics in a Vatican document to pick up a book for their own good certainly is. According to Francis’ incarnational approach to reading and art, God is in all things — including poems and stories that might not be written for a spiritual purpose.

Francis shares an anecdote from his days as a teacher that will ring familiar for most educators. He was tasked with teaching his students “El Cid,” a sprawling poem that celebrated Castilian knight Rodrigo Díaz de Viva. His teenage students complained; they wanted to read the poet Federico García Lorca instead. A shrewd teacher, Francis compromised: if they read “El Cid” at home, they would read contemporary poetry in class. The contemporary work hooked the students, and made them want to read more — and read more broadly.

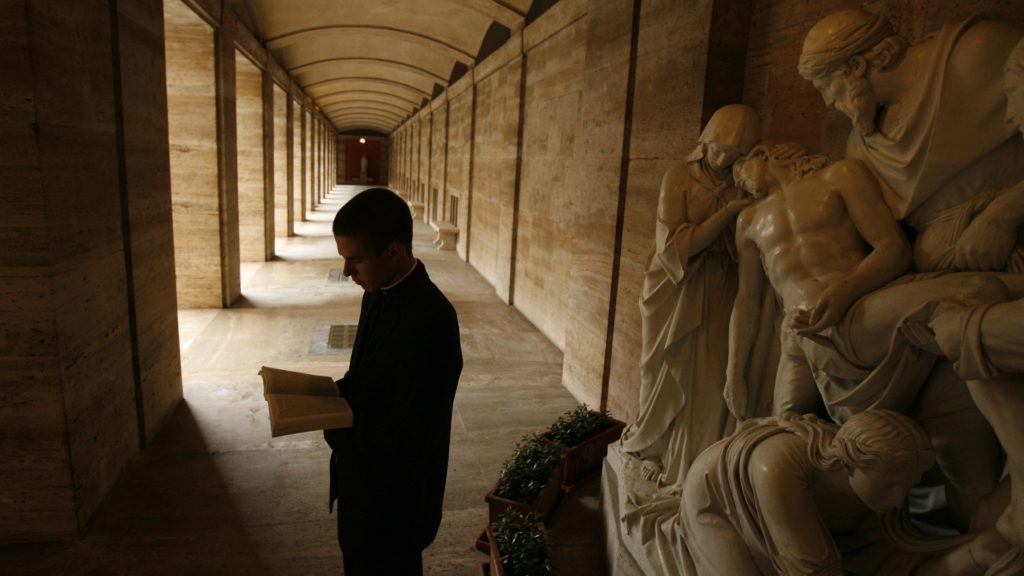

At the time, Francis was teaching at Immaculate Conception College in Santa Fé, Argentina, as a Jesuit seminarian. As a teacher myself, I can affirm that it takes having to teach literature in order to truly understand it. As a 28-year-old seminarian, Jorge Mario Bergoglio was being formed by — perhaps discerned through — literature.

In his letter, Francis sees three particular benefits of literature for priestly formation. First, literature “sets language in motion, liberates and purifies it.” Political and ideological discourse stunts language, replacing the complexity of life with empty slogans. Literature, in contrast, “opens our human words to welcome the Word that is already present in human speech.” Literary study can help priests sharpen their writing and speech, and in doing so, polish the Church’s message and expression.

Second, study of literature can help seminarians in their life as missionaries of Christ. Reading poetry and fiction helps us see other cultures in action; the more we read, the less we see ourselves, and instead Christ, as the center. Francis affirms that engagement “with different literary and grammatical styles will always allow us to explore more deeply the polyphony of divine revelation without impoverishing it or reducing it to our own needs or ways of thinking.”

Last, literary study will model powerful, concrete storytelling for seminarians. It is notable that Francis does not focus on monastic, scholarly study here; he sees storytelling as helping priests dramatize the “flesh” of Christ: “that flesh made of passions, emotions and feelings, words that challenge and console, hands that touch and heal, looks that liberate and encourage, flesh made of hospitality, forgiveness, indignation, courage, fearlessness; in a word, love.”

The final theme of Francis’ letter is the idea of the priest as poet and artist. Here he draws from the work of 20th-century Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner, who felt that “the poetic word calls upon the word of God.” Francis sees a literary component to the task of “naming” the world, an action “assigned by God to Adam,” and inherited by priests. In doing so, priests “[bestow] meaning” and “[become] instruments of communion between creation and the Word made flesh and his power to shed light on every dimension of our human condition.” In this sense, priests are poets because of their spiritual imaginations — and Francis suggests they can offer the faithful an enlivened language for belief.

Francis’ vision echoes that of the Catholic media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who in 1959 spoke with seminarians at St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto. McLuhan also likened priests to artists, extolling them to recognize the similarity between emptying their needs and wants and becoming a vessel for Christ, and how artists create. Like priests, the “artist’s role is not to stress himself or his own point of view but to let things sing and talk, to release the forms within them.”

For those who are called to bring Christ to the world — priests and the laity alike — such a vision is pure poetry.