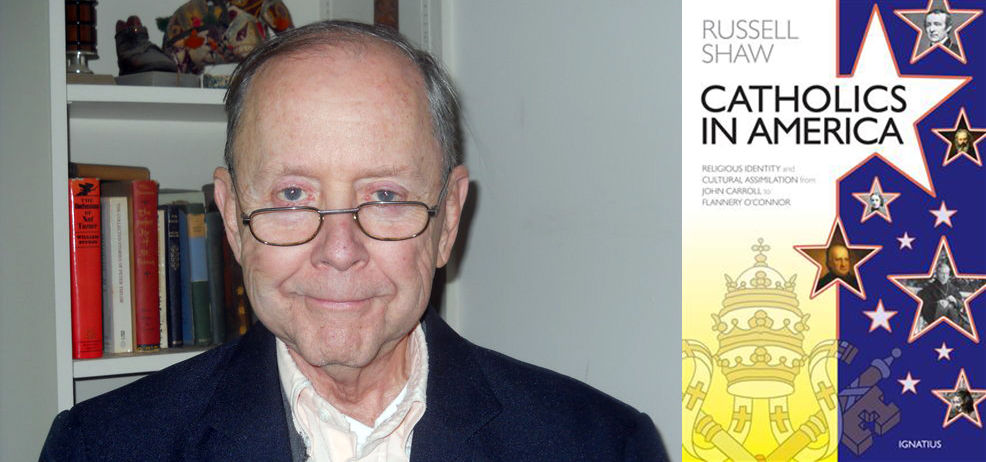

We are not of this world, and yet, while we’re here we have some serious obligations, including as citizens. Politics can be a challenging matter of conscience, as we’ve had close encounters with of late, and will continue to. Russell Shaw is a veteran writing about the Church and the public square, the author, most recently, of a book on Catholics in America: Religious Identity and Cultural Assimilation from John Carroll to Flannery O'Connor. In an interview, Shaw talks about the present, past, and future of Catholics in America.

Kathryn Jean Lopez: This past Election Day was Dorothy Day’s birthday. What’s the bipartisan challenge she offers?

Russell Shaw: Day was a radical Christian—radical on moral issues, radical on economics and human rights. And when I say “radical,” I mean radical in the sense of going to the roots of Christianity and embracing what she found there. Neither of our two big parties looks anything like that, and you could say that makes Day a bipartisan challenge to both. But I hardly expect either party to reshape its platform around radical Christianity. The parties are and will remain loose coalitions of interest groups. Of course there’s been some talk lately about trying to launch a new “consistent ethic of life” party, and that might be something like what Dorothy Day personified. I’d like to see it happen, but I don’t expect it will.

Lopez: In the wake of the Trump win do you expect more assimilation or is there a possibility for some bold, authentic leadership? Could there be a roll back in secular hostility to real religious faith and conscience rights, outside Sabbath worship?

Shaw: The late Cardinal George of Chicago saw the problem with cultural assimilation very clearly and spoke out against it. Archbishop Chaput of Philadelphia is doing that now. And there are others. But most pastoral leadership is pretty bland, focused on internal matters and propping up the declining infrastructure of the Church. In fairness, too, I’m not sure what anybody could do or say to reverse the assimilation process—which, after all, is simply one aspect of the much more powerful global process of secularization. As for secular hostility to religious faith and conscience rights, there isn’t much chance of a rollback. This is hostility with its source in ideology, and the people pressing it are ideologues whose minds are made up.

Lopez: There’s a lot of controversy over the Al Smith dinner every four years and what kind of message it sends about the Church to the culture, so to speak. Should it stay or should it go? Or should it be changed? It’s not a light question as it brings a lot of money in for charity!

Shaw: I think the purpose of the dinner—over and above fundraising for a good cause, I mean—needs to be more sharply defined. It was clear enough when this was a way of asserting the Catholic presence in American political and social life. But now? Maybe making it a public celebration of religious liberty would help. And then making it clear to the speakers that this was what they were expected to talk about.

Lopez: What is it about Al Smith that people should know?

Shaw: Confronting an upsurge of vicious anti-Catholicism during his presidential campaign in 1928, Smith didn’t back away from his commitment to the Church. That’s changed a lot since Smith’s day, and in my book I link the change to John Kennedy’s famous speech to the Protestant ministers in 1960 when he promised that as president he wouldn’t let his faith influence him. Since then many other Catholic politicians have rushed to do the same on issues like abortion and same-sex marriage. Just consider Tim Kaine during the recent campaign. Back to Smith, I say.

Lopez: Are there people alive today who you see as prospective profiles for another book, a few decades from now? You mention figures like Thomas Merton and Theodore Hesburgh and Walker Percy perhaps eventually getting a place in such a volume by historians down the line but is there anyone among the living who might eventually fit such a bill? I ask not to prematurely write history or canonize or anything like that, but to encourage.

Shaw: They aren’t among the living, but I would certainly add Cardinal Bernardin of Chicago and Mother Angelica of EWTN fame to my list of great American Catholics in a new edition of the book. As for those living now, it’s hard to say. I have tremendous admiration for Archbishop Chaput, whom I’ve already mentioned, and I would very much like to see a Hispanic leader like Archbishop Gomez of Los Angeles emerge on the national scene. We’ll see.

Lopez: What should every Catholic in America know about Archbishop John Carroll? Especially if they’ve found religious freedom of increasing importance and worthy of gratitude and protection?

Shaw: Archbishop Carroll was the right man in the right place at the right time. He became the leader of the Catholic community in America when it was very small, very weak, and in a precarious state. He recognized the Church’s problems, faced up to them, and worked out and applied effective strategies for dealing with them. The assimilation project got its start with him. The problems of American Catholicism are very different today, and cultural assimilation now is part of many of them. But just as in Carroll’s day, so now we need intelligent and creative leadership to bolster our religious identity.

Lopez: What do you think Pope Francis is up to with some of his recent American appointments? Including giving Newark a cardinal?

Shaw: There’s no mystery about it. He’s reshaping the hierarchy to carry out his program for American Catholicism and, among the cardinals, to provide the votes needed to elect as his successor someone who will continue his program at the level of the universal Church.

Lopez: Was there a lasting impact to his visit last year? Should there be?

Shaw: People have asked that question for years about the visits by St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict. Now we ask it about Pope Francis. I wish I could say, “Yes, the visit had a big impact, and here’s the evidence.” But I don’t see it like that. If there was a lasting impact—and perhaps there was—it happened in the hearts of individuals, and that is something you can’t see and measure. I hope there was.

Lopez: How can the immigrant experience through the lives of Cardinal Hughes and Mother Cabrini influence some of our current debate? And in ways practical to a Trump White House reality?

Shaw: One big lesson of American Catholic immigration is that immigration is a traumatic experience both for the immigrants and for the Church. It seems to me the Church in the United States has learned from its previous experience and made a serious effort to respond positively to the influx of Hispanic immigrants in recent decades. Now we’re apparently going to have a fight over immigration with the Trump administration. Too bad, but if there’s got to be a fight, let’s get on with it.

Lopez: You’ve written previously about the “American Church” and its “uncertain future.” What does the election of a first Hispanic as vice president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic bishops— Los Angeles Archbishop Gomez of Los Angeles — mean for the future of the Church in America?

Shaw: Symbolically, the election of Archbishop Gomez is very important since it points to the emergence of Hispanics as a major presence in U.S. Catholicism. So does the very substantial amount of time and attention the American bishops devoted to Hispanic issues during their general assembly in November. But welcome as this is, it comes pretty late. As Cardinal O’Malley pointed out during the bishops’ meeting, the Church in America has been losing young Hispanics in large numbers for years. Serious efforts to remedy that are urgently needed, and the sooner the better.

Lopez: What about the Americas? There have been a few conferences in recent years, put on by the Vatican commission on Latin America and the Knights of Columbus bringing together Catholic leaders — including many bishops -- from all of the Americas, which recent popes have looked to as one continent. Is that realistic? How could that help matters like religious freedom and other thorny political issues?

Shaw: A sense of solidarity with Latin American Catholicism would be extremely helpful to the Church in the United States as it tries to rise to the challenge of the Hispanic presence we’ve been talking about. People in this country have been shockingly ignorant of the political and cultural realities to the south for a long time. That has to stop, and Catholics would be doing themselves and everybody else a favor if they led the way.

Lopez: Is there a reckoning that needs to be had as far as Catholics and their relationship to political parties and how that shapes parties?

Shaw: Too many Catholics vote Democratic because they’ve always voted Democratic, or Republican because they always vote that way. That encourages the parties to take them for granted at the same time that it robs them of any distinctive religious identity as far as their political participation is concerned. And it’s a disastrous instance of the split between faith and life that the Second Vatican Council condemned in no uncertain terms. We pay for it in many ways, including a diminished influence on politics and public policy—a diminished role for the Church in American life.