A few years ago, Karen Kiefer walked into the children’s section of a Barnes and Nobles to buy a gift. Unable to find a single Christian title, she approached an employee to ask where she might find one.

“There might be one or two in ‘religion,’ ” the staff member guessed. “We don’t have any in the children’s section. That [decision] comes from corporate.”

Not long after, Kiefer overheard two young children talking in the grocery store.

“You shouldn’t talk about God in school, because it makes people feel uncomfortable,” one instructed the other.

As a mother of four girls in their teens and 20s, Kiefer was no stranger to the secularizing culture’s influence on children and adolescents — she just hadn’t thought God was officially off-limits.

Within days, Kiefer, who serves as the director of the Church in the 21st Century Center at Boston College, found herself writing the children’s book “Drawing God” (Paraclete Press, $18.99).

Grounded in St. Ignatius of Loyola’s maxim that we can “find God in all things,” the book tells the story of an aspiring artist named Emma, whose depictions of God as bread, love, and light at first confound but then inspire her peers to share how they, too, experience God.

Five years after its publication, more than 1 million children have shared their artistic depictions of God in a virtual museum.

Kiefer is part of a wave of Catholics whose academic and professional work now includes creating children’s literature.

Some are motivated to counter the ideological capture of children’s minds, which Pope Francis has cautioned against. Others want to match the quality of biblical narrative they find in Protestant children’s books. And more than a few want books about faith or virtue to grab and sustain children’s attention in the way best-selling secular books do.

No matter the difference in motivation, it’s easy to spot a unifying thread — it’s Catholic parents driving this movement. Not having found the books they want for their own children, they’ve decided to create them themselves.

“There’s definitely a renaissance happening with children’s literature,” said Haley Stewart, author of “The Grace of Enough: Living with Less in a Throwaway Culture” (Ave Maria Press, $16.95), “Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life: On Love, Friendship, and Becoming the Person God Created You to Be” (Ave Maria Press, $16.91), and “The Sister Seraphina Mysteries” (Pauline Press).

“One piece of it has to do with the growth of the classical education and homeschooling movements,” she said, noting how COVID-19 exposed not only what children were reading, but that they were reading at record low levels.

Stewart is the editor of Word on Fire Votive, the children’s imprint of Bishop Robert Barron’s apostolate.

When asked why Word on Fire, known for its academic and theological publications, ventured into this space, Stewart said they “didn’t want to miss the window of evangelizing within the domestic church.”

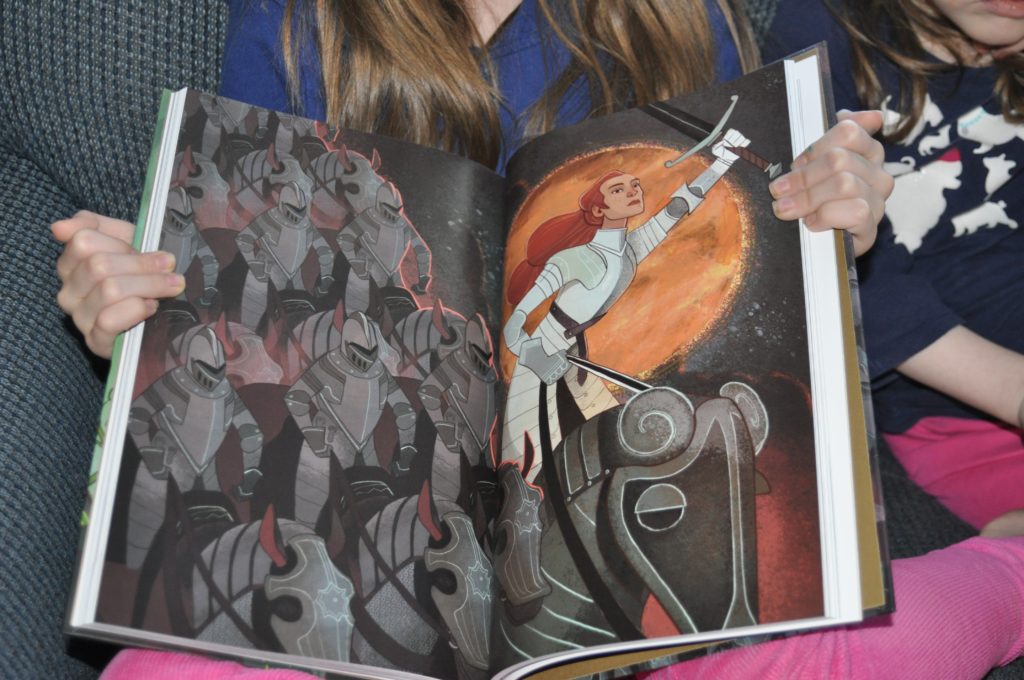

“Kids need stories that help them believe that they can transcend and conquer things that are hard and dark,” she insisted. “The narratives of materialism and scientism don’t offer that.”

“Our kids are despairing because the stories they are bombarded with, especially on social media, lead them to think that the world has no real purpose.”

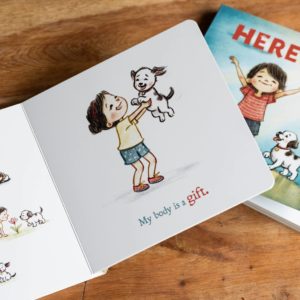

The imprint recently published the board book “Here I Am” ($19.95) by University of Notre Dame professor Abigail Favale, whose scholarship is focused on sexual difference and embodiment.

Favale told Stewart on the Votive podcast that the text for the children’s book came to her while she was reading to her 2-year-old. She wanted kids to have a better narrative of gender than a “simplistic one [that says] what activities you like determine if you are a boy or a girl.”

“When you root gender in the body, there’s actually more freedom for the unique personality of each child to unfold,” she said. She hopes the book builds a child’s imagination so they view the body “as a gift and something that reveals their personhood.”

Stewart wants to help parents and children build a library of high-quality, beautiful books so that storytelling more easily becomes part of family culture. “We want children to develop a taste for beauty and goodness as well as the Gospel,” she said.

The benefits of shared reading have been well-documented by Wall Street Street Journal children’s book critic Meghan Cox Gurdon. In “The Enchanted Hour: The Miraculous Power of Reading Aloud in the Age of Distraction” (Harper Paperbacks, $18.99), Gurdon explores the neurological, emotional, and psychological benefits experienced by children whose parents read to them, including increased brain activation, better attention span, and strong family bonds.

When asked how parents should approach new children’s literature, Gurdon cautioned, “Anyone can write a children’s book, but not everyone can write a great children’s book.”

The greats, in her estimation, draw children out of themselves and into worlds riddled with struggle, trial, and conflict.

“Today’s parents are so alarmed when they see things that might be upsetting,” she lamented.

“I didn’t want my own children being afraid of ‘going into the woods’ where things were scary. I wanted them exposed to ideas like cowardice, courage, fear, and beauty.”

While Gurdon does find new publications to recommend along with the classics, she is often frustrated that most children’s books sold to libraries and schools today are filled with tropes and contrived plots. “They are way too didactic,” she cautioned.

That’s something motivating Claire Swinarski, a Midwestern mother of three and author of middle-grade fiction.

“I’ve always had a heart for middle-schoolers trying to figure out who they are and what they believe,” she said. “Books were such a companion to me during some hard years.”

Not long after Googling “How to get a literary agent,” Swinarski published her first novel, “What Happens Next” ($17.98) in 2021 with Harper Collins. Since then she has been nominated for an Edgar award and published four more novels, including one for adults.

Swinarski is glad to see more books about kids from diverse backgrounds and life experiences, but laments that publishers often want books to be “big and loud” with a “commercial hook.”

“My favorite books were about normal kids having normal problems or average conflicts,” she said. “Kids don’t need to read about other kids starting massive movements or saving the world in order to have their hearts shaped.”

A few years ago, Catholic biblical scholar Scott Hahn was approached by parents and grandparents about making his books accessible for children. The result is a project for Hahn’s St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology headed by Catholic writer Emily Stimpson Chapman, who has written memoirs and co-authored several theological books with Hahn.

To date, they have published “Mary, Mother of All” ($17.95) and “The Supper of the Lamb” ($17.95). Six more titles are in the works.

While it was important for Chapman that they went “toe to toe” with mainstream children’s literature in terms of look and feel, it was equally important to get the rhyme, meter, and emphasis correct.

“My kids can recite my books just like they can recite ‘Little Blue Truck’ and “Goodnight, Goodnight Construction Site,’ ” she said. “You want the truths of our faith to easily stick in their minds.”

Chapman was also commissioned to write a children’s Bible for Word on Fire.

“I wrote each narrative with the aim of drawing the reader into the excitement and drama of the salvation story,” she said, citing how she presents the crucifixion as Christ battling for us on Calvary. The Bible is set to be released in 2025.

Not surprisingly, sometimes the inspiration for children’s books comes from children themselves.

“My kids are my test market and live-in models,” joked Meg Whalen, a Florida-based illustrator, who studied theology at the Augustine Institute while taking art classes at Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design in Denver, Colorado.

After graduating and starting her family, Meg was on the playroom floor with her Augustine Institute classmate, Katie Warner, when their conversation turned to books they wished they had to introduce their children to Scripture, the liturgy, vocations, and saints.

Using her background in public relations, Warner pitched TAN books on starting a children’s line, and they have collaborated with the publishing house ever since.

Whalen and Warner’s joint titles include “The Tiny Seed: A Parable” ($16.95), “Father Ben Gets Ready for Mass” ($16.95), and “Oremus: Latin Prayers for Young Catholics” ($18.95), which features illustrations based on some of the masters.

One of Warner’s books, “Listening for God: Silence Practice for Little Ones” ($16.95), was inspired by her desire to help her own children begin to lay the foundation for silent prayer.

Time will tell how these books will bear fruit in the lives of the children who read them.

“A book can’t change the world, but a child who reads one can,” said Kiefer, whose books are now available on Barnes and Nobles’ website.

“The truths these books contain are for everyone,” added Chapman. “Children’s literature is never just for kids, since there’s a child at the heart of every one of us.”