How to respond to a world racked by war, in an age of lies, intrigues, and fading faith? The answer may lie in the art of a man named Caspar David Friedrich, born 250 years ago this month.

This German painter, who captured the sublime beauty of God through nature, might have a lesson or two for today’s turbulent world. Son of a soap boiler and candlemaker, Friedrich was born into a world facing a critical juncture: Earth-shattering revolutions were brewing in the fledgling United States and in France, while his hometown of Greifswald on the Baltic coast would pass from Sweden to France to Denmark and finally Prussia during his lifetime.

Death took its toll both far and near: While still a child, he lost his mother, two sisters, and brothers, and as a young man several of his friends were killed resisting Napoleon’s invasions. France’s Reign of Terror violently excised religion, and the lame Jacobin substitute, the Cult of Reason, could not fill the void left by the eradicated faith.

Friedrich was no warrior, accustomed to wielding a pencil rather than a sword. At age 16, he went to study with Johann Gottfried Quistorp, learning to draw from models, but was much more interested in the outdoors. At this time, he met theologian Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten, who taught that nature was a form of divine revelation, which would deeply affect the art of the young painter.

Friedrich was raised Lutheran in an era when religion was falling out of style. Suffering, however, was omnipresent. The Napoleonic wars cost 3-6 million lives between civilians and soldiers, and the accompanying poverty and disease claimed even more. But in 1808, as Denmark declared war on his homeland Sweden and Napoleon invaded the papal states, Friedrich produced a work for King Gustav IV Adolph of Sweden, which, in its quiet grandeur, would revolutionize art and offer hope in the darkest hour.

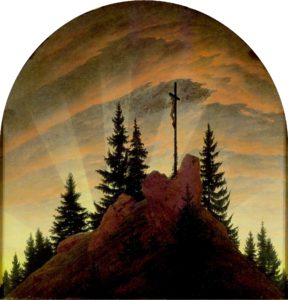

“Cross in the Mountains,” the first work to bring the 34-year-old Friedrich renown, was painted to encourage the deepening faith of the Swedish monarch. Both painter and prince were influenced by the Moravian Brethren, a spirituality of interior devotion — a “theology of the heart.” Gustav, however, abdicated a year later and the work went to Tetschen castle, home of the Catholic Count Thun-Hohenstein, where it served as an altarpiece.

The work features a gipfelkreuz, or summit cross, a type of landmark erected in the 13th century along mountain passes of the Alps. The cross appears as a slender reed among the more densely clad fir trees below. The corpus turns away from the viewer, unthinkable in medieval art, rare in Renaissance art, but increasingly employed during the Baroque era. The viewer gazes from behind as if standing by the lone tree on the dark rocky slope.

Below the rugged cliffside one would expect to find pastures and villages, which, approaching the plain, become cities that then grow into nations. Those nations, in 1808, were relentlessly, brutally, at war.

From the turbulent darkness, the eye is drawn to Christ, who repels the shadows. Jesus’ radiance not only commands attention but instills a longing to be in the line of his gaze and within the embrace of his outstretched arms. He mediates between this dark and light, a meeting between the search for clarity and the mystery that is man’s final destiny. He is the invisible made visible. Serene skies hint at a hope for peace while the mountain, at first an obstacle, slowly becomes the anchor of the work, the embodiment of steadfast faith.

Later, Friedrich would write of this work, “Jesus Christ, nailed to the tree, is turned here towards the setting sun, the image of the eternal life-giving Father … The cross stands high on a rock, firm and unshakable like our faith in Christ.”

Friedrich’s innovative approach to landscape dwarfed his figures with the overwhelming power of nature, upending traditional imagery where man had always dominated nature. The move garnered scorn from many of his contemporaries, yet his depiction of the sublime, awe-inspiring yet frightening, seems to resonate with anyone who feels overwhelmed by events beyond our control.

Friedrich followed “Cross in the Mountains” with “Monk by the Sea,” sweeping the viewer from a mountaintop to a deserted beach where fog and wave and shore all seem to become one. A lone figure dressed in a cassock and identified as a monk (perhaps a portrait of the artist) stands on a narrow strip of sand. The rules of perspective seem to have been washed away like so much flotsam by the wall of mist rising above the figure. The inky sea rises to a charcoal haze, through which menacing masses seem to loom.

The slight figure of the monk contemplates the vastness of nature before him, his erect posture conveying no fear. A few pearlescent gulls lead the eye from the impending storm toward the luminous sky above. Friedrich’s scene suggests that prayerful solitude before the terrifying abyss of existence allows one to perceive the light of hope through despair. Friedrich reprised this idea in what would become his most popular work, “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” (1818), where the man gazing into the abyss becomes everyman (or woman for that matter) facing the great unknown.

Friedrich intended “Monk by the Sea” to be paired with his “Abbey in the Oakwood,” painted a year later. Here, the artist leads the viewer into a snowy valley amid a tangle of dead trees, their knotty branches evoking either menacing claws or gesticulating mourners. Through the mist, a splendid stone arch holds court among the trees. The high lancet window with its traces of fine carving recalls the beauty created by man when directed to God, instead of the destruction caused when man follows his basest nature.

The attentive observer will note a group of monks carrying a coffin through the ancient graveyard. A seemingly random cross on the right leans toward an open grave yawning between the viewer and the doorway, a rustic memento mori. Life begins, flourishes, and ends, such is the cycle of existence. Though the mood is melancholy, the light on the horizon recalls Pandora’s box, after all the evils have been released to devastate the world, and only one thing remains, hope. Light in the art of Friedrich evokes hope not only in troubled times, but also in lonely souls.

Though he evoked faith through images of crucifixes, monks, and dilapidated abbeys, Friedrich remained Lutheran throughout his life. While several of his fellow German Romantic painters, Philipp Veit, Johann Friedrich Overbeck, and Wilhelm von Schadow converted to Catholicism and founded the Nazarene movement of religious history painting, Friedrich’s artistic voice remained unique, and, in a certain sense more ecumenical, as it used the majesty and mystery of nature to reveal the divine.

Friedrich endured criticism for allowing landscape painting “to sneak” into sacred spaces, a criticism that allowed these masterpieces to fade into obscurity. Once rediscovered, Adolf Hitler championed their depiction of Germany’s distinct topography, earning them guilt by association and relegating them to another historical oubliette. These misguided attempts to categorize his work stalled his success, dimming how Friedrich, during an age of animosity toward religion, successfully returned faith to the public square through nature.

Eighteenth-century industry relied on timber and forests to be felled in the name of progress; Germans pioneered forest management, coining the term Nachhaltigkeit, or “sustainability.” Seen in this light, the poignant trees and desolate seascapes of Friedrich’s oeuvre appear as a Romantic version of Laudato Si (“Praise Be to You”). That Hitler, dealer of death extraordinaire, collected his works, reveals the Führer’s deep ignorance of this artist who endeavored to be an instrument of peace.

Whether mountain tops, sea mists, or snowscapes, Friedrich drew natural barriers intended to block out the noise of media and machinations, and to evoke the silence of prayer. At last, Feb. 8 to May 11, 2025, Americans too will be able to enjoy the brilliance of this underappreciated master when the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York will host an exhibit entitled “Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature.”

Friedrich’s anniversary offers a wonderful opportunity to rediscover this beautiful art: a beacon of peace and hope rendered through the universal language of God’s creation.