Rosemary Mahoney goes where others fear to tread.

Her first book, “A Likely Story: One Summer with Lillian Hellman,” chronicled her summer on Martha’s Vineyard as a live-in housekeeper for the prickly playwright. For “The Singular Pilgrim: Travels on Sacred Ground,” she braved the icy waters at Lourdes, watched corpses floating down the Ganges in Varanasi, and completed the hellish St. Patrick’s Purgatory in Ireland.

“Down the Nile: Alone in a Fisherman’s Skiff” is the tale of the season she flew to Luxor, acquired a 7-foot rowboat, and set out down the crocodile-infested river, musing on fellow Egyptologists Florence Nightingale and Gustave Flaubert.

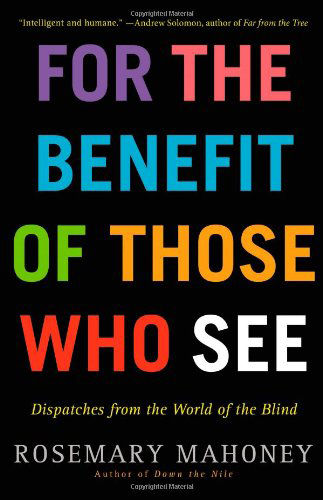

Mahoney’s newest book, “For the Benefit of Those Who See,”is part travel memoir, part history, part science: a personal account of going halfway across the world to learn about and teach the blind.

In Tibet, she meets Sabriye Tenberken, the determined, resourceful woman — herself blind — who founded the school Braille Without Borders. From there, she travels to Kerala, India and teaches at the school Tenberken has established there for blind adults.

Mahoney’s great gift is what might be called micro-observation: She takes an “ordinary” moment and considers, masticates and describes in thrilling detail, extracting every last bit of meat. She notices the way people’s jaws move, the rhythm and idiom of their speech, the sound of the air, the smell of trees.

Here’s her description of 12-year-old Kyumi:

“His one visible eye was glassed over with a film of unnatural glacial blue, and the other eye was rolled downward into its inner corner, which made him look as though he were trying to analyze the flare of his own nostril. Periodically Kyumi would flap his hands in the air in a rapid violent shaking fashion, as if trying to rid them of flames or caustic acid.”

For Mahoney’s own part, the physical world is almost “hypervivid to me.” Within minutes of meeting someone for the first time, she will have noticed whether he’s missing a button on a shirt cuff, the hair between his knuckles, the shape and length of his fingernails.

But the blind, she discovers, take observation, awareness and acute sensitivity of their surroundings to new heights. They also depend upon and trust each other in a way sighted people rarely “have” to:

“I had noticed that when the blind children were sitting idly together, they always sat huddled close and draped about one another — arms slung around necks, elbows linked, heads gently touching, hands entwined with hands…This constant connecting of hands was not just a gesture of affection but a form of communication, a way of conveying and receiving subtle emotions and even ideas, much the same way sighted people convey emotions or thought with glances and facial expressions. The children’s eyes reflected nothing of their moods or thoughts but rolled uselessly, like milky blue marbles. It was only their hands and their voices that revealed them.”

Mahoney scours the Bible, reads Greek and Roman mythology, and ponders why “across the ages, society’s attitude toward blindness has remained hostile.” The matter-of-fact resilience of the students is counter-balanced by their darknesses, wounds and silences. Many of them come from villages where they were shunned, tormented, locked in closets, or put to work as beggars.

One day Mahoney dons a blindfold and goes into town accompanied by two of her female students, Yangchen and Choden. She’s astonished at their sure-footed way they weave their way among buses, animals and hordes of jostling people. They know the entrance to the temple by feeling “the ground has changed” with their feet and their white canes. They know they are in front of the Buddha statue by the smell of the beer people leave as an offering. Plus, as Yangchen notes, “We can read in the dark.” Small wonder that the blind often consider themselves superior to the sighted.

They also “process” human interactions in a very different way than the rest of us.

“I once asked Jessie, blind since birth, how she imagined human faces,” Mahoney writes. “Her quick response was ‘I don’t.’ A person’s face was not, for her, the locus of an individual’s being.”

In fact, perhaps the most mysterious facet of blindness is that the restoration of sight is often a mixed blessing. The previously sighted have trouble connecting the sight of, say, a fork with an actual fork and can only identify an object by feeling it with their hands. Faces tend to confuse rather than console. Sidney Bradford, a British cobbler whose sight was restored at the age of 52, began to notice “the blemishes in things.” He died seven months later.

“Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” the disciples ask. Jesus replies, “Neither he nor his parents sinned; it is so that the works of God might be made visible through him” [John 9:2-3].

Or as Catholic novelist Flannery O’Connor said of the lupus that would kill her at the age of 39, “I can, with one eye squinted, take it all as a blessing.”

Heather King is the author of “Parched: A Memoir,” “Redeemed: Stumbling Toward God,” and “Shirt of Flame: A Year with St. Therese of Lisieux.” She lives in Los Angeles.