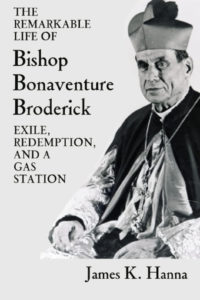

Perhaps the greatest tribute you can give to biographers is to finish their work and ask to read more. Such was my reaction after reading Catholic historian James K. Hanna’s “The Remarkable Life of Bishop Bonaventure Broderick” (Serif Press, $15.99).

The son of Irish American parents in Hartford, Connecticut, Broderick’s life is a story of extraordinary successes and failures. When he decided to pursue the priesthood at the age of 20, he had already, in his own words, “achieved phenomenal success” in the world of business. Once in the seminary, his gifts as a student led his bishop to send him to study in Rome to earn a doctorate in sacred theology.

His personality and intelligence seem to have been a two-edged sword. He attracted the support of influential people, but also intense antipathy. Once back in Hartford, he grew close to his bishop and eventually convinced him to lend money to a munitions factory belonging to his brother. The business venture failed and the bishop, after losing $10,000 of diocesan money, tried to exile Broderick to the ecclesiastical hinterland. Broderick refused, insisting it was not his fault, despite the affair making national news headlines. Broderick never seemed to lack self-confidence.

He was rescued from the failure at Hartford when the Vatican appointed him secretary to the new bishop of Havana, Cuba, who had been his teacher in Rome. This was in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, and the Catholic Church in Cuba, which had depended on the government of Spain for sustenance, was in disarray. Broderick, ordained a priest in 1896, was made a monsignor by Pope Leo XIII in 1901.

His time in Cuba was the most brilliant part of his career. His close relationships to the Americans in government in Cuba, and other powerful people, including U.S. Secretary of State Elihu Root and Sen. Mark Hanna of Ohio, made it possible for him to influence some important settlements, including negotiating a return of church properties that had been commandeered by the Spanish government.

Thanks to a series of ecclesiastical maneuvers, Broderick, whose usefulness with the Americans was exceptional, remained in Cuba and was made auxiliary bishop of Havana, ordained in 1903 at the tender age of 34.

Trouble came again. It seems strange to me, but the bishop was a partner in a huge project building infrastructure in Cuba — a sewer project in Santiago — and hired one of his brothers, David. The business deals went awry, and years later Broderick would eventually be involved in a series of lawsuits involving various persons, including the governor of New York and his brother.

Perhaps the business issue is why the Vatican ambassador to Cuba who had consecrated the young Broderick as a bishop, Archbishop Placide Chapelle, turned from promoter to “persecutor” according to Hanna, who does not speculate on reasons. After only a short time as auxiliary bishop, Broderick faced opposition in Havana. Chapelle went to Rome to complain about him, and Broderick followed him there to defend himself, taking with him his mother and her caregiver, a former nun with whom he had worked in Cuba.

The new pope at the time, St. Pius X arranged a pension from the Church in Cuba and named Broderick, a gifted fundraiser, to oversee the Peter’s Pence Collection in the U.S. He also made plans to assign him as auxiliary bishop of Baltimore, with residence in Washington, D.C., without bothering to consult the local bishop. Cardinal Gibbons, archbishop of Baltimore, was adamantly opposed to both aspects of the plan. Pretty soon the young bishop ended up without a diocese and without a job.

He tried to find work, and even got President Teddy Roosevelt to support his idea for a system that would draw Italian immigrants away from crowded cities and into villages in Virginia where they could continue their agricultural work. The plan failed miserably, and Broderick took up residence in New York.

Broderick had some personal income but ended up spending a great deal of time in court while waiting for an assignment from Rome that never came. He wrote a letter to St. Pius X arguing that his situation would give scandal, which the pope took as a threat. And the rest was silence, for a long time.

He said Mass privately for his mother and her caregiver, was involved with the community in which he lived independently, but had no connection with Church life. He tried his hand at farming, was popular with his mostly wealthy neighbors, who knew him as “Doctor” Broderick, and wrote for a small weekly newspaper from 1937 to 1939. Hanna has edited a collection of the bishop’s columns titled “The Wit and Wisdom of Bishop Bonaventure Broderick.” The writings reveal a very cultured man, an America First-er, and a critic of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (whose family home was not far from Millbrook, where the bishop lived).

Because of the Great Depression, perhaps, the bishop found himself in financial difficulty. He invested in a gas station and auto parts store in the 1930s. He lived in quiet exile. Then in 1939, after 34 years in the ecclesiastical cold, came something of a miracle: the archbishop of New York knocked on his door.

Archbishop (later Cardinal) Francis Spellman got a lot of bad press from critics over the years. But his compassion with Broderick is a story of grace, assigning the 70-year-old prelate to a nursing home as a chaplain to a congregation of sisters, and making him an auxiliary bishop of New York. Broderick sold his home and business and went to live with the sisters, who loved him and who told stories about how the bishop would talk of Cuba with tears in his eyes. Three years after the return to ministry, Broderick died in the arms of Holy Mother Church. It is an extraordinary story, puzzling and with many missing pieces, but also heartwarming.

Like the mythological character Icarus, the ambitious and brilliant young cleric flew a bit too close to the sun. James Hanna and Serif Press have done a service to the Church in America publishing these two books on a man Hanna describes as a “curious footnote” in the recorded history of the Church in America. There must be more to all this than Hanna shows, but the human dynamic in the Church, the sweep of ecclesiastical history, and God’s everlastingly ironic Providence make Broderick’s story well worth reading and reflecting upon.