What does the Catholic Church have to say about this? Or that?

For the last 2,000 years, the answers have often come from figures like popes and cardinals, but also more ordinary men and women now recognized as saints.

Lately, the subjects of those questions are often more complicated — and their answers more controversial. In an age marked by reawakened racial tensions, artificial intelligence, movements of mass immigration, shifting views on identity, gender, and sex, the proliferation of piecemeal wars, and the specter of a post-pandemic global “Great Reset,” what are ordinary Catholics supposed to think? For Bishop Robert Barron, the answers are out there, but it helps to know where to look.

On April 21, Barron participated in a wide-ranging Reddit “Ask Me Anything” session that drew skepticism and praise on social media for his thoughts on modern trends like Critical race theory and “wokeism.” The controversy comes amid the release of the latest volume in the Word on Fire Classics series, the “Catholic Social Teaching Collection” (Word on Fire, $29.95), that asks readers to consider wisdom from popes and saints past and present.

Angelus spoke to Bishop Barron, who oversees the Archdiocese of Los Angeles’ Santa Barbara Pastoral Region as an auxiliary bishop, about what the collection’s excerpts have to say to the troubles roiling our society.

Bishop, what gave you the idea to compile this book, and why release it now?

I have long been passionate about Catholic Social Teaching (CST). For many years, I offered a course at Mundelein Seminary on this subject, and I paid special attention to the social doctrine articulated by the popes of the past 120 years. I feel that the Church’s social doctrine, like the documents of Vatican II, is still largely unknown to huge numbers of Catholics. I wanted this text to serve as a useful introduction to this tradition.

In the introduction to the book, you write that “the idea that the Church shouldn’t have a social teaching is simply repugnant to the Catholic view of God.” Where do you see that view being expressed right now?

I would like to first explain what I mean by this. For classical Catholic theology, God is not one being among many, but rather the sheer act of “to-be itself,” “ipsum esse” in the language of St. Thomas Aquinas. This means that God is intimately present to all of creation and to every aspect of life, very much including the social and political order.

We ought, therefore, never to think of economics and politics as secular, if by that term we mean divorced from God and God’s purposes. I think there is, within some quarters of the Catholic world, a tendency to bifurcate the secular and the spiritual too radically.

One inclusion that surprised me was that of “Sublimis Deus,” Pope Paul III’s encyclical condemning the enslavement of American natives centuries before the major world powers — and later the U.S. — ended slavery. It doesn’t sound like it would have been the most popular thing for the pope to say at the time. Do you see any parallels with the Church’s teachings on any of today’s “hot-button” social issues?

I love that text, and I have enormous admiration for Bartolomé de las Casas, the Dominican friar and advocate of the native peoples, who played a key role in its development.

You’re right. Long before the European powers moved to end slavery, the Church condemned the practice, and in so doing contributed mightily to what would eventually emerge as a movement on behalf of universal human rights. To be sure, there were many violations of this teaching within the Church in the centuries following this declaration, but it certainly represented a crucial turning point.

When the Church speaks out today on behalf of migrants, the poor, those who are discriminated against because of their race, etc., it is continuing in the tradition of Las Casas and his colleagues.

You’ve talked and written a bit lately about the problems with “wokeism,” to the chagrin of some Catholics sympathetic to the aims of today’s social justice movement. Do you see the text on CST compiled in your book as an antidote to the legacy of Marx, Nietzsche, and Foucault in Western culture today?

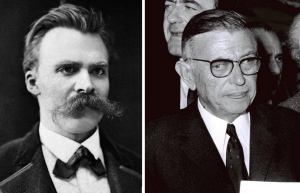

Yes! The advocates of the so-called “woke” ideology today have not been shy about articulating the philosophical underpinnings of their perspective. They do indeed find inspiration in Marx, Nietzsche, Sartre, Derrida, and Foucault, among others.

From these modern and postmodern thinkers, they derive a number of principles.

First, they advocate a deeply antagonistic social theory, whereby the world is divided sharply into the two classes of oppressors and oppressed.

Second, they relativize moral value and see classical morality as an attempt by the ruling class to maintain itself in power.

Third, they focus, not so much on the individual, as on racial and ethnic categories and hence they endorse the idea of collective guilt and recommend a sort of reverse discrimination to address the injustices of the past.

Fourth, they tend to demonize the market economy and the institutions of democracy as part of a superstructure defending the privileged.

Fifth, they push toward equity of outcome throughout the society, rather than equality of opportunity.

And finally, “wokeism” employs divisive and aggressive strategies of accusation that are contrary to the Gospel demand to love our enemies.

Suffice it to say that Catholic Social Teaching stands athwart all of this. It wants social justice, of course, but not on “woke” terms. Its heroes are not Marx, Nietzsche, and Foucault, but rather Isaiah, Amos, Jeremiah, Jesus the Lord, Ambrose, Aquinas, and Teresa of Calcutta.

I fear that a lot of Catholics, legitimately concerned about societal injustice and eager to do something about it, will turn, not to our biblically based and deeply wise social teaching tradition, but rather to the philosophy that’s currently in the air. That’s a main reason I wanted to bring this collection out.

Couldn’t the argument be made that Catholics included in the second half of the book — figures like Dorothy Day and saints like Teresa of Calcutta and Oscar Romero — were “woke” in their own right?

No! I mean, if you want to define “woke” as simply being alert to social injustice and passionate about addressing it, then sure, they were “woke.”

But the term, as I clarified above, has a much more definite meaning, and those great figures would not be the least bit sympathetic with contemporary “wokeism,” it seems to me. For one thing, all three of them believed deeply in God and in the objectivity of moral values, and all three of them advocated a cooperative social theory. And none of them believed in programs of collective guilt.

In an April 15 address to the Minnesota Catholic Conference, Archbishop José H. Gomez said that “in the Catholic vision, social justice is not about personal identity, or group power, or getting more material goods.” Is there a “contributor” to this book that you find elaborates on that view particularly well?

In saying that, Archbishop Gomez is echoing the voices of Leo XIII, Pius XI, John XXIII, Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis, the present Bishop of Rome — all of whom are represented in our book.

In the excerpt from “Evangelium Vitae” included in the collection, John Paul II acknowledges the difficulty in mounting “an effective legal defense of life in pluralistic democracies, because of the presence of strong cultural currents with differing outlooks." Today it seems the Church is praised in mainstream culture when she speaks out on issues like the death penalty and racism, but less on the fundamental right to human life. What is the best way to do that in 2021?

When it comes to matters of intrinsic evil that seriously compromise the common good, the Church must speak strongly and clearly.

As Pope John Paul II often reminded us, the Church never imposes, only proposes. So, even as we acknowledge the difficulty of persuading people of our point of view, we are obliged to make cogent public arguments about all of the great life issues: abortion, capital punishment, euthanasia, racism, etc.

Depending on the question, of course, we will be more popular with the left or the right within our American context. So be it. Our job is not to please any political party. It is to speak for Gospel values in the public square.

Your apostolate, Word on Fire, has tried to reach people where they seem to spend a lot of time nowadays — online. So what’s the idea behind releasing this Word on Fire Classics series in print?

I certainly believe in the importance of using the new media in evangelization, but I have always been, deep down, a book person. And Word on Fire, from the beginning, has been a publishing enterprise.

Last year, we brought out the first volume of our Word on Fire Bible, which we envision to be a seven-volume project, and just a few weeks ago we published a book containing the four constitutions of the Second Vatican Council, accompanied by commentary by the post-conciliar popes. So I’m delighted when people watch my videos, but I also want them to read!