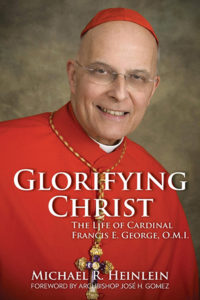

At one point in Michael Heinlein’s well-researched biography of Cardinal Francis George, “Glorifying Christ: The Life of Cardinal Francis E. George, O.M.I.” (Our Sunday Visitor Press, $29.95) the author writes, “Without question, suffering defined much of George’s life.”

There was a great deal of physical suffering in the prelate’s life, starting when he contracted polio at 13 years old. Polio left him lame for the rest of his life and subject to many surgical interventions. On top of the pain and inconvenience consequent to the disease, George had two different bouts with cancer. The first, in 2006, required radical surgery and the construction of an artificial bladder. The second bout hit him in 2012. He fought it off for two years before he died.

Heinlein notes that the cardinal hardly complained about his health. In the forward to the book, Archbishop José H. Gomez notes, “I had forgotten how bravely [Cardinal George] had carried out his public ministry.” Archbishop Gomez emphasized that the spiritual suffering George endured while serving the Archdiocese of Chicago illustrated the power of sacrifice and prayer: “His honesty in confronting his challenges reminded me of something St. Paul said: ‘There is the daily pressure upon me of my anxiety for all the churches’ ” (2 Corinthians 4:15).

That sort of suffering began when he joined the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, after being told he could never be accepted as a seminarian of the Archdiocese of Chicago due to his illness. A tremendously gifted student, he had been advanced to an academic career, then was elected a very young provincial and later served as vicar general of the Oblates in Rome for 12 years. While in that post, he visited Oblate missions in many different countries, which refined his aptitude and appreciation for other cultures.

But he was also affected by the confusion his congregation suffered after the Second Vatican Council, when 304 priests requested laicization and 450 brothers under temporary vows left between 1969 and 1974. In that year, the general of the Oblates resigned without completing his term to marry an ex-religious. Provinces had to be closed, and the declining numbers and the spiritual malaise of the congregation affected George a great deal.

Rome, according to his former liberal colleagues, had caused him to make a “right turn.” His superior said his newfound “prudence” or “conservatism” was the product of his idealism meeting “reality.” Later, George concluded that “Liberal Catholicism is an exhausted project.”

After his time in Rome, George worked for a brief time with a think-tank focused on faith and culture that Cardinal Bernard Law was promoting in Boston. He was developing a program of Oblate spirituality for laypeople when he was named bishop of Yakima, Washington. From there, he became the archbishop of Portland, Oregon. Just 11 months later, he was named archbishop of his home city.

In his installation message at Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral, he emphasized to the archdiocesan community that he was a “neighbor,” a native. Nevertheless, Chicago was a tough assignment. Years before, his predecessor Cardinal Joseph Bernardin had told George that his see was “sometimes ungovernable.” The hometown boy met a great deal of resistance, including from priests and his own bureaucrats in the chancery.

He had had many challenging jobs before, but George confessed that “I came with the expectation it would take me a while, but eventually we’ll get the hang of it. And I have a very hard time working into it.”

Made a cardinal a year after arriving in Chicago, George was much consulted by St. Pope John Paul II and eventually elected president of the country’s bishops.

He had to deal with the sexual abuse crisis, both in his diocese and on national and international levels. There were also all sorts of issues in the diocese, particularly with schools and parishes closing. At one point, he suggested he might sell the bishop’s residence to raise money for schools, but experienced pushback from those who could not accept losing a historic landmark.

A brilliant man, he was also impatient at times. George Weigel relays the reaction of an auxiliary bishop to the news of George’s appointment to Chicago. “Oh no,” said the prelate, “he’s the one who gets up at meetings and uses all those words the bishops can’t understand.” A double doctorate (philosophy and theology) and a gift for concise analysis and expression were sometimes barriers for his brother priests.

Paul Simon once sang about a man who “wore his passion like a thorny crown.” I think George wore the mitre of Archbishop of Chicago the same way. There was a moment when he concluded that “Chicago is locked into patterns of self-destruction that I am powerless to change.”

The same year he was elected president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2009, he was diagnosed with cancer. A year later, he was chosen to work at a Roman synod, and two years after that, to a commission of cardinals examining the reform of the Vatican curia. Duty-driven, he said that “I’ve always done what I was told to do, basically. My life isn’t self-constructed.” This was true until the end.

His was a life of self-sacrifice. Anyone who reads this biography will be impressed by the prophetic integrity of the man. His books are a legacy, as are some of his famous perceptions, such as this: “I expect to die in my bed. My successor will die in prison, and his successor will die a martyr. [The martyr’s] successor will pick up the shards of a ruined society and slowly help rebuild civilization, as the Church has done so often in human history.”

This was not a literal prediction but an example of prophetic eloquence, something of which his writings are a rich treasury. A mind of great culture and deep thought joined to a heart completely given to Christ and in love with the Church, Cardinal Francis George had and still has a lot to give to us. Heinlein’s biography is well worth careful reading.