Thanks to a virus that has brought the world to a standstill, achieving focus and productivity feel like a Sisyphean task. Even as some sectors of the economy slowly reopen, there’s a palpable uneasiness caused by the sudden unpredictably of what’s going to happen next.

It’s an uneasiness that pop culture has tried to capture for years, often using dystopian themes that resonate more deeply today than we could have ever imagined.

Take “The Twilight Zone,” for example, which brought the post-World War II anxieties of the Atomic Age to the small screen. The episode “Time Enough at Last” is an eerily prescient story for a time when people are trying to navigate the blurry line between solitude and loneliness while holed up in their homes.

Burgess Meredith stars as bespectacled bank teller Henry Bemis who has a penchant for books. Despite protests from his boss and wife, he values nothing more than time alone to read. After a nuclear explosion, Henry finds himself the last man in existence.

It’s a troubled fate made better for the bookworm by the discovery of a library filled with undamaged books. In a typically bleak “Twilight Zone” plot twist, Henry’s glasses break, rendering him nearly blind and unable to read.

“That's not fair. That's not fair at all,” bemoans Henry. “There was time now. There was all the time I needed.”

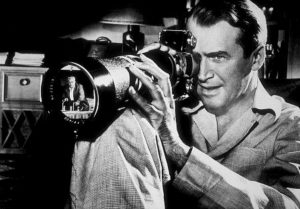

Before “Twilight Zone,” the great American director Alfred Hitchcock made us feel the loneliness of confinement with 1954’s “Rear Window.” The story about an injured, homebound photographer who believes he has witnessed a murder unfolds through the perspective of James Stewart’s character, Jeff.

He gazes out his apartment window at the neighbors he only knows by made-up nicknames. Our view of the narrative is limited to his. The compositional frames of windows and doorways entrap us with each character, making us complicit in Jeff’s voyeuristic compulsions.

Stanley Kubrick looked at the extremes of isolation in his adaptation of Stephen King's “The Shining,” about the breakdown of a family that moves to a remote hotel in the Colorado Rockies to become off-season caretakers.

Kubrick confronts us with our own murky subconscious and the strange, dark places it sometimes leads us. Like the book, the film veers into supernatural territory, and “The Shining’s” labyrinthine centerpiece, the imposing Overlook Hotel, becomes the stage for a battle between ultimate good and evil.

The mystery of human motivation and suffering is also at the heart of a 2019 film by director Robert Eggers, “The Lighthouse,” recently available to stream on Amazon Prime. On a remote New England island chiseled by the fury of the sea, a grizzled lighthouse keeper (Willem Dafoe) and his tight-lipped apprentice (Robert Pattinson) descend into madness as violent storms keep them stranded in isolation atop the rocks.

By night, the sailors become entranced by the lighthouse’s hypnotic beam. Eggers’ claustrophobic tale of seafaring horror revels in its graphic, intrusive masculinity and scatalogical humor, but it’s one of several intentional choices that become agents for exploring identity.

The black-and-white format and boxy 1.19:1 aspect ratio limits what the viewer can see, confining us to the characters’ miserable existence fraught with memories and fantasies they can’t escape, perhaps the greatest torment of isolation. Both men are named Thomas, which comes from Aramaic origin, meaning “twin.”

“How long have we been on this rock? ... Where are we? Help me to recollect. Who are you again, Tommy?” asks Dafoe’s character. They are at once trapped by their grotesque humanity and closer than ever to touching the gods through the lighthouse, their Mount Olympus, the “heavenly threshold” of Homer’s “Iliad.”

“Ghost stories appeal to our craving for immortality,” Kubrick once said. “If you can be afraid of a ghost, then you have to believe that a ghost may exist. And if a ghost exists, then oblivion might not be the end.”

While Julio Quintana’s 2016 Terrence Malick-produced film “The Vessel” doesn’t portray phantoms in a traditional sense, grief still haunts the hearts and minds of its protagonists. Set years after a deadly tsunami took the lives of a Puerto Rican village’s schoolchildren, the townspeople have yet to be consoled despite the efforts of a tenacious priest, Father Douglas (Martin Sheen).

One young man, Leo, struggles with loss, tending to his distraught mother, who seems to favor his deceased brother, and a love interest who clings to the memory of her late husband. The villagers are transformed when Leo has an accident but appears to return from the dead, like Lazarus. He decides to build a boat from scraps of the old schoolhouse, reigniting hope and faith within the community.

Unlike many movies that explore similar themes, “The Vessel” proposes although there are seasons of life that bring us pain, suffering, and loss, these are burdens we don’t carry alone.

In his 1984 apostolic letter “Salvifici Doloris” (“Redemptive Suffering”), St. Pope John Paul II asserted that suffering is “a universal theme that accompanies man at every point on earth: in a certain sense it co-exists with him in the world, and thus demands to be constantly reconsidered.”

Suffering is not fully reconciled by the end of “The Vessel.” Leo still questions if he will ever fully reach a place of interconnectedness through his pain, but his healing has begun. Suffering, in this way, is a sacred mystery.

Perhaps he could have used the words of the late saint in “Salvifici Doloris”: “This is the meaning of suffering, which is truly supernatural and at the same time human. It is supernatural because it is rooted in the divine mystery of the Redemption of the world, and it is likewise deeply human, because in it the person discovers himself, his own humanity, his own dignity, his own mission.”