At my last parish assignment, I would have a celebration of the Word of God every Monday with the students of the parochial school. Out of 150 students, perhaps there were eight who were baptized Catholics.

When it came to choosing the Gospel reading for one of these Monday gatherings last Lent, I was confronted with two options based on the liturgical year: John 8:1–11 or John 11:1–45. Instead of reading about the woman the USCCB children’s version said was caught “sleeping” with a man not her husband, I went with Lazarus for the kiddos.

There are all sorts of statistics about infidelity in America, both adultery and what is usually called “cheating” between unmarried couples. It is practically impossible to know with certainty to quantify the problem, but it is obvious it is a serious problem. A recent experience of a millionaire’s problem with a jumbotron got a lot of attention.

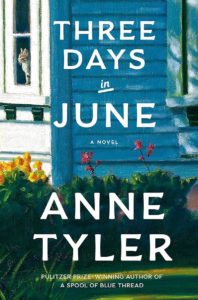

That is why I am impressed with Anne Tyler’s latest novel, which is a kind of lighthearted and heartwarming take on the problem of infidelity.

I know that sounds oxymoronic. But the book, “Three Days in June” (Knopf, $27), deals with the issue admirably while still managing to be, in the words of one of the blurbs on the book jacket, “a warm, witty and wise instant classic about second chances.”

Tyler, who is 83 years old and has won whole walls of literary awards and distinctions, has been called an “American Middle-Class Jane Austen” because of the subtlety and humor of her many novels. She has published numerous short stories and 25 novels, of which six have been given film adaptations. “The Accidental Tourist” (Vintage, $18) is one that is well known.

This is not like most fiction about adultery. In this slender novel that can be read in a matter of a few hours, Tyler shows her ability to draw portraits of her characters that make them seem real and funny and sympathetic at the same time. The plot is set around three days in which a daughter of a divorced couple gets married. Without giving away the plot, there are two instances of infidelity that arise.

The novel inspired me to reread Albert Camus’ famous short fiction, “The Adulterous Woman” (Penguin, $5.05), the title and theme a reference to the Scripture story. The woman, one of the so-called pied noir group of French citizens who were born and lived in colonial Algeria, doesn’t commit adultery physically on a trip with her husband in Algeria. But she is more than just slightly tempted, and her sullen merchant husband is totally unaware of it. At the end of the story, she begins to cry in the hotel room the couple stay in and yet cannot explain why. There are tears in Tyler’s novel, too, but no sentimentalism.

Emotion is not the same as sentimental feeling. Not being able to explain emotion is a hallmark of the people in Tyler’s fiction. We understand her characters very often before they understand themselves. William Faulkner said that the sources of good writing are observation, experience, and imagination, although a writer with two out of the three could do well.

Tyler has a detailed power of observation that makes you see the father of the bride and his wrinkled sports jacket and khaki pants, the dynamics of a group of people feeling awkward at a wedding rehearsal, the tears of her characters. It makes you hear their voices, communicating to us despite the misused words and inane comments.

Her recreation of the book’s setting, Baltimore, is the work of both observation and imagination, but the latter is especially present in the artistry of the dynamics between the characters. We sense the connection between the people in the kaleidoscope of impressions and many flashbacks. The narrator is acerbic and sometimes very funny but reveals much more than she intends about herself. We expect to laugh as a character goes down “the rabbit hole” of recounting a dream he had, and we are gratified when he does.

I don’t know what kind of life experience Tyler has had. But she has a quality of humanity that sounds like wisdom. She holds up a mirror to nature and yet gives us hope about befuddled people who work against their own happiness.

Oscar Wilde said that “nothing looks so like innocence as an indiscretion.” The indiscretions of the characters in this novel are pivots for the plot, but also keys to understanding how complicated human beings can be, how fragile and how challenged they are to change. We are not swept up in dramatic actions of exceptional people but get involved in the lives of what seem to be ordinary people in both ordinary and inevitable situations.

The characters in the novel are not like Gustave Flaubert’s “Madame Bovary” (Fingerprint! Publishing, $5.99) or Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” (Fingerprint! Publishing, $24.99). They are not tortured souls dragged to their destruction by desperate, futile, and destructive attempts at happiness. The people in “Three Days in June” make stupid mistakes and then struggle to see a way out of their disappointment with themselves. We can laugh even as we feel contrary emotions. Tyler’s prose is light, saturated with references to popular American culture, and her wit is understated. The list of the songs at the wedding reception rings so true, it seems like we have crashed the party.

Perhaps it was the juxtaposition in time of reading and preaching about Jesus and the woman caught in adultery days before I read the novel, but I related Tyler’s work, like I did Camus’ short story, to the Gospel incident.

Tyler’s ending of the novel is a new beginning, like Jesus’ saving the woman’s life. Where did the lady go from there? How did she reflect God’s mercy? In “Three Days in June,” the persons involved in infidelity do not explicitly seek forgiveness of God, but they do of their partners, not in the same way, and not so articulated, but we can see what they are striving for without words.

In one of Tyler’s books, some characters go to worship in the Church of Second Chances. This octogenarian writer is inviting us all to the same place in this book, too. I think Jesus would approve of the message.