Just over 25 years ago, Andrew McCarthy was trying to run away from his reputation.

A member of the infamous ’80s “Brat Pack,” McCarthy was just as well known for his history of partying and drugs as he was for his starring roles in “Pretty in Pink,” “St. Elmo’s Fire,” and “Weekend at Bernie’s.” Attempting to flee public perception and its effect on his own self-image, McCarthy ran to Spain.

More accurately, he walked there — nearly 500 miles on the Camino de Santiago, a pilgrimage dating from the Middle Ages from the French city of St. Jean-Pied-du-Port to the traditional burial site of St. James the Great in northwest Spain.

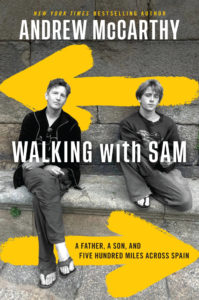

McCarthy’s 2023 book, “Walking with Sam” (Grand Central Publishing, $28) jumps forward 25 years. Still best known for his role in the Brat Pack, McCarthy has grown a larger career which includes acting, directing, and travel writing. He’s also raised a son, the eponymous Sam, who has joined his father’s second trip on the Way of St. James.

What follows is part memoir-part travelogue with a dash of history. But mostly it is a love letter to one of the most enduring pilgrimages in Europe and a glimpse into the raw heart and experience of a pilgrim.

“While we all walk the same route — millions of us over the centuries — no one walks the same Camino. In a very real way, this trip is a private one,” he writes.

The private trip is laid bare for the reader, who follows McCarthy’s wandering mind through a painful relationship with his father and the feelings of insecurity that arise in his own fatherhood. Less explicit yet still consistent throughout the pilgrimage are peaks into McCarthy’s own spiritual journey.

McCarthy is among the nearly 16 million Americans who say they were brought up Catholic but now identify with no religious tradition.

“I long ago walked away from the dogma of my religion,” McCarthy writes, “even as seeds of a spiritual connection to something beyond my comprehension began to grow in me.”

McCarthy never dives much deeper into the structure of his “spiritual connection,” besides referencing his choice not to raise his children — including fellow pilgrim Sam — according to any formal faith tradition.

Instead, McCarthy uses the five-week walk across Spain to simply be present to his son — providing a listening ear as Sam works through his first adult breakup, sharing some of his own personal baggage but very rarely sharing advice.

“Let the Camino do its work, I silently remind myself,” McCarthy said. “Just walk along beside him.”

Some readers might find the elder McCarthy goes too far in his laissez faire approach to his son’s travails and adolescent habits, but it does impart a lesson in listening — especially those committed to the kind of accompaniment called for by Pope Francis.

McCarthy’s challenge is to learn how to treat his son as a fellow adult while still maintaining paternal love and responsibility. Along the Way, his patronizing morphs into respect.

Yet his accompaniment is wanting, not only because of the author’s freely admitted faults, but because the entire exercise is lacking a solid footing. McCarthy’s Camino differs from the medieval one because it is detached from Christian tradition.

Repopularized by books and movies — including the 2010 film “The Way” by fellow Brat Pack alum Emilio Estevez — the Way of St. James has become choked with walkers, new hostels, and even (as McCarthy recounts during a stay at his favorite town of O Cebreiro) a thriving bus-tour trade.

The glut of pilgrims with no connection to faith have also called into question the historical veracity of St. James’ final resting place. And while McCarthy may find mythology of anecdotal interest, past pains with the institutional Church keep him from seeing the Way of St. James as more than a good, long walk.

“What I didn’t understand then was that the institutions … protect themselves first, no matter the platitudes and slogans they boast,” he writes of the school systems that failed his son.

In the book, he references a nun who plays the scrooge, chasing the father-son duo from a hostel with rude demands of payment; historical injustices committed by the Knights Templar and the Franco regime along the Way; and, of course, the decades of clerical sexual abuse that injured so many and poisoned trust of Catholic leadership.

“While I was vehement in my outrage,” McCarthy writes about the abuse crisis, “Sam bypassed my repulsion and left the church to its own devices.”

The line is possibly the most heartbreaking in the book. Throughout the memoir, Sam is depicted almost as a caricature of Gen Z — foul-mouthed, late-rising, gender-inclusive, and constantly spouting the latest slang. And, in this instance, so completely detached from Catholic institutions that he faces scandal with apathy rather than his father’s antipathy.

It’s a painful reminder of the challenge that faces the modern Church: attracting souls either so wounded by failed Catholic leaders or so numbed by them that the Gospel’s foothold in the West seems to be slipping.

Yet even in the face of this apparent uphill battle, a look back on the Camino offers a foundational piece of hope.

“Legend goes on to tell us that after Christ’s crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension, James headed off to the Iberian Peninsula in order to preach the Word,” McCarthy explains. “But he seemed to lack persuasiveness, or at least the oratory skills required to hold a crowd. He attracted just seven disciples for his troubles.”

In 2022, a record 438,182 pilgrims completed the Way of St. James. The Camino is a long journey on foot. The road to faith is also a long journey for some. St. James is still at work.