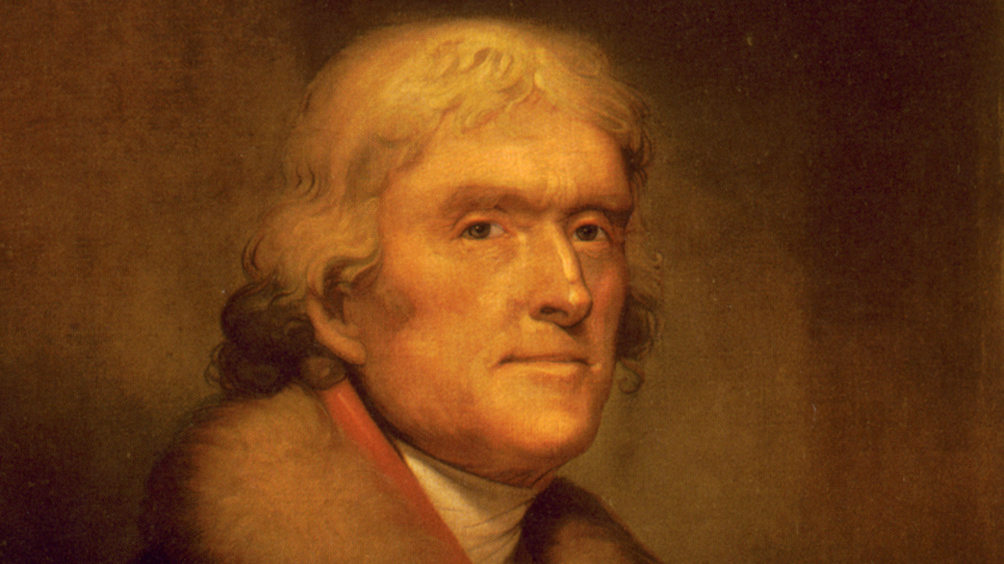

“I am of a sect by myself,” wrote Thomas Jefferson when he was 76 years old and almost finished with what today is called the “Jefferson Bible.”

This year marks the bicentennial of its completion, presenting an occasion to take a fresh look at a unique American artifact now housed at the Smithsonian Institution. By almost any definition, the “Jefferson Bible” is a heretical document, but also, paradoxically, an unexpected source of potential inspiration.

Think of it as a one-man Jesus seminar. The fellow from Monticello lived long before the now-defunct group of scholars who made headlines in the 1980s for voting on the authenticity of the sayings of Jesus by dropping colored beads into a box. Whereas they craved publicity and concocted a media-savvy stunt, Jefferson worked in private.

He mentioned his project in occasional letters, yet he did not publish the final result. His mission, nevertheless, was similar in its fundamentals. He aimed to study the Gospels and edit them into what he regarded as the truest possible account of history’s greatest figure: a human Jesus rescued by reason from revelation.

Raised in the Anglican tradition, Jefferson turned doubtful “from a very early part of my life,” he once confessed. The idea of the Trinity perplexed him: “I never had enough sense to comprehend” the doctrine. Soon he fell away from orthodoxy.

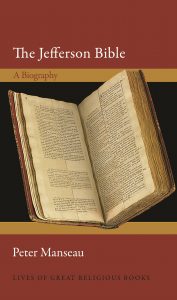

In his excellent new book, “The Jefferson Bible: A Biography” (Princeton University Press, $24.95), Peter Manseau labels this a “quiet rebellion.” A noisy rebellion might have ended Jefferson’s political career before it even had started, of course. Contemporaries who spoke loudly about their skepticism took their chances with an 18th-century version of cancel culture.

Despite his reservations about religion, Jefferson took faith seriously. The Declaration of Independence, which he drafted, includes a deistic reference to “the Law of Nature and Nature’s God.” About a decade later, he wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. It became a forerunner to the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment.

Jefferson was so proud of this law that he had his authorship of it etched onto his gravestone, which doesn’t bother to mention that he was also America’s third president.

Jefferson was a public figure with a secretive streak: We still don’t know with absolute certainty whether he fathered several children with his slave Sally Hemings, though the evidence is circumstantially strong in our era of DNA testing.

While he avoided pronouncements about his personal religious beliefs, he read the Bible and thought deeply about Christianity. In 1804 and 1805, as he transitioned from his first presidential term to his second, he bought six copies of the New Testament in four languages.

“They likely sat for several years on a White House bookshelf in the room Jefferson called his cabinet,” writes Manseau. In time, they became the raw material for a remarkable scrapbook.

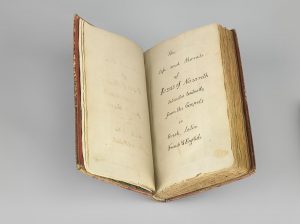

The “Jefferson Bible” was his great retirement project, but he called it something different: “The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.” The handwritten title page added that the work had been “Extracted textually from the Gospels in Greek, Latin, French, & English.”

That’s a good description of what Jefferson did. He sliced up those copies of the New Testament that he had moved from Washington to Monticello and rearranged their contents by gluing strips of text into an 84-page, multilingual volume that retold the story of Jesus in a single narrative.

Mostly it involved deletion: Jefferson removed all the parts that he found implausible. His goal was to scrape away the barnacles of supernaturalism that had attached themselves to the account of a real historical person whom he regarded as a great moral teacher but also a mere mortal.

The “Jefferson Bible” wipes out all claims of divinity and eliminates every miracle. Adoring shepherds at the Nativity? Gone. Loaves and fishes? Scratched. Walking on water? Left on the cutting-room floor. Jefferson took a special interest in what Jesus said. In a letter to John Adams, he boasted that distinguishing between the true and phony statements was “as easy … as to pick out diamonds from dunghills.”

The “Jefferson Bible” concludes with a death, a death by crucifixion, but otherwise a plain and ordinary human death. Its mashed-up final line is a good example of Jefferson’s method, as it yokes together parts of John 19:42 and Matthew 27:60 to produce a single sentence: “There laid they Jesus, and rolled a great stone to the door of the sepulchre, and departed.” There is no resurrection. The end.

This bowdlerized tale is a heresy, a deviation from the standards of Christian faith. Critics have condemned what Jefferson did, and it’s hard to deny their central point, which is that the Gospels are a package deal. Christians may enjoy favorite verses, but they are not free to pick and choose the parts they believe and those they disbelieve. Conventional biblical interpretation permits creativity, debate, and mystery. It doesn’t allow redaction and reassembly.

What the most bitter critics sometimes have missed, however, is the fact that much of the fascination that surrounds the “Jefferson Bible” has nothing to do with its theology and everything to do with the man who compiled it. If there were such a thing as a Millard Fillmore Bible, we probably wouldn’t bother with it.

We certainly wouldn’t have an affordable full-color facsimile edition published by the Smithsonian, following a careful and costly conservation effort. (The “Smithsonian Edition” is the best way to read the “Jefferson Bible,” and the new book by Manseau is the perfect companion volume for understanding its context.)

The text of the “Jefferson Bible” is, in fact, boring. Without an empty tomb, it’s an empty tale, and it’s hard to imagine that Jefferson’s Jesus could have inspired a Faith that has lasted for two millennia. The “Jefferson Bible” turns the Gospels into “Monty Python’s Life of Brian,” except that it’s not funny.

So it may be tempting for a Christian to dismiss the work as the misbegotten product of an unserious mind, tossing it onto one of Jefferson’s dunghills. Yet there’s another approach. It just requires a willingness to look on the bright side.

Around the globe, Christians face many threats, including violence. A greater menace, at least in the United States and much of the developed world, may be indifference, a pervasive dispassion that comes not from an honest rejection of the faith but from a failure ever to grapple with it.

Nobody can remain utterly indifferent to faith for long, though in the absence of a commitment to a traditional religion, people will turn to the idols of ideology, which can feed the hostility that Christians sometimes face from secular culture. A partial answer to this problem is a commitment to the principles of religious freedom that Jefferson himself pioneered. A more complete solution is to read the Bible.

Ever since Cyrus Adler of the Smithsonian Institution discovered the Jefferson Bible in the 1890s and Congress funded its first publication in 1904, the work has generated every possible reaction, from curiosity and admiration to disgust and denunciation.

As Manseau observes in his book, the ways in which Americans have received the “Jefferson Bible” may be more interesting than the ways by which Jefferson conceived it. The one thing that can’t be said about the “Jefferson Bible,” however, is that it is a product of indifference.

Jefferson knew the Gospels better than many of his detractors. “I never go to bed without an hour, or half an hour’s previous reading of something moral,” he once wrote. Readers don’t have to approve of what he did to recognize and even appreciate his sincere effort. One of America’s greatest minds thought long and hard about the world’s most important words. Shouldn’t we all?

The best response may be a merciful one: to forgive what Jefferson got wrong and to encourage what he did right. This was Paul’s approach on Mars Hill. He didn’t condemn the Athenians for their paganism and unknown god. Instead, he congratulated them for how they perceived the truth of Christianity, however dimly. Then he taught them the truth.