Artificial intelligence (AI) systems are having their moment. AI image generators such as MidJourney have proven capable of creating almost any picture imaginable — even a fake but compelling image of Pope Francis in a chic puffer coat. Meanwhile, advanced “chatbot” systems such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT continue to stun the public by mimicking human speech with almost frightening accuracy.

But one team of researchers is seeking to put AI to use for a different and more noble purpose — the translation of the Bible into extremely rare languages.

Ulf Hermjakob and Joel Mathew are researchers at the University of Southern California’s Information Sciences Institute in Marina Del Rey, California. They recently launched Greek Room, a computer program designed to streamline the process of Bible translation by providing needed quality-control services such as spell checking for translation drafts created by humans.

“We don’t think that AI can replace the human translator. We see it as a support role to help in this very challenging task of translating the Bible into languages where there’s often almost no written records of any kind,” Hermjakob, a native of Germany and a Ph.D. computer scientist, told CNA.

Hermjakob, a lifelong Lutheran, said despite the Bible being the world’s most translated book, it has so far been translated into only about 700 of the world’s 7,000 languages, which excludes many languages that have several thousand speakers — rare, yes, but far from tiny.

“The main target we have is a community of maybe 100,000 speakers. It could be somewhat less, it could be somewhat more, but typically it’s not languages that are going to die out within the next 10 years where there’s like 10 octogenarians left — that’s typically not the target group,” he explained.

Mathew, an engineer who works mainly in the field of natural language processing, was born to Christian parents in India and came to California to obtain his master’s degree. Mathew identifies as a nondenominational Christian and remains active in his church community. He told CNA the importance of having a Bible for speakers of relatively rare languages can’t be overstated, as he has seen it firsthand among Christian communities back home in India.

“It’s life-altering for communities — the joy and tears that it brings to people to have printed book in their ‘heart language,’” he said, referring to the language that people speak at home and most identify with.

“Having the word of God in your own heart language is very meaningful. And unlike in the past, where Bible translation was more of an agenda of a bigger agency, there is the local church now taking the initiative and saying, ‘We want the Bible in our heart language, because we are a bunch of believers here in this small language group, and we are now excited to have the Bible in our language.’ So that’s kind of shifted the model.”

(For Catholics, translations of the Bible must be approved by the Vatican or the appropriate bishops’ conference before they can be published.)

What does the AI do?

Spell checkers for major languages like English have existed for a while, but for languages with only a few thousand speakers, commercial spell-checking software simply doesn’t exist, Hermjakob said.

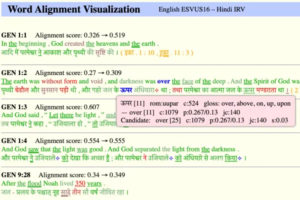

The Greek Room’s software can scan drafts of the translation and look for inconsistencies in spelling, flagging them for the user. It can also scan the text and make sure the alignment of the words appears to be correct, and again can flag inconsistencies for the translator. For a lengthy and technical translation such as the Bible, such tools can save the translator a lot of time and effort. Not everything the AI flags will be actual errors, but it will provide a helpful list of items for the human translators to look at and discuss, Mathew noted.

An example of Greek Room's word ordering tool working on a translation from English to Hindi. (Greek Room via CNA)

The software can also present a “menu” of terms from other translations in an effort to help the translator choose a word for difficult terms. The example Hermjakob gave was for the term “battering ram,” which doesn’t have an equivalent in some languages. In this case, the software’s suggestions can help the translators choose a word in their language that makes sense.

Mathew and Hermjakob both made it clear that their program is not intended to be an all-in-one solution for translating the Bible. The process requires a small team of native speakers of the rare language — ideally Christians — who also know a second, more common language such as English or French. The computer program is designed to “learn” from the native speakers of the rare language and will be able to pick up more words and grammar from the language the more input it is given.

“Generally you would not do this [translation work] in isolation, you would do this as teams and in association with a local body of believers, Christians, so that there is generally quick feedback on what you are drafting. So the human element for all of us is extremely important,” Mathew continued.