Despite the suffering and strife in the Middle Ages, Dante Alighieri believed that beauty could save the world, and he used his pen to prove it.

As the world marks 700 years since the death of Italy’s most celebrated poet, it is sobering to reflect that in our present language-obsessed culture, few share Dante’s belief in the beauty of words. Dante dreamed of forming a language to unify and inspire. What would he make of our weaponized words and their constantly changing meanings?

“Dante,” as history has remembered him, was born in Florence, then a republic, around 1265. The son of a wealthy family, he lived as the increasing number of well-to-do young men did in the affluent mercantile cities: military service, guild enrollment, formal education, marriage, and politics.

His status allowed him to pursue his passion for philosophy and poetry, so he continued his studies at the University of Bologna. where he joined the poets of the “sweet new style,” a term coined by Dante to describe the courtly love poems written in new types of verse, spiced with lofty allegories and symbols.

The idyllic existence of these young artists, absorbed in love and letters, was set against a backdrop of violence and uncertainty. Italy, a political patchwork of republics, dukedoms, and turf claimed by the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was in a constant state of armed conflict.

Pope Celestine V, the spiritual glue of Europe, had shocked Christendom by resigning after only a few months, followed by his death under suspicious circumstances. His successor, Pope Boniface VIII, appeared more interested in influencing temporal affairs than shepherding souls.

The lack of unity was exacerbated by the chaos of language, with differing dialects evolving according to each region’s geopolitical reality and with Latin increasingly reserved for the learned and the clergy.

All the while, Dante and his band of erudite troubadours sang of love in their catchy rhythms. Dante hit a sour note, however, when his diplomatic activities brought him into conflict with the opposing political faction in Florence. Once his enemies rose to power through a violent takeover of the city, they turned on the poet in absentia, sentencing him to exile for life.

The banished bard responded to the injustice, humiliation, and penury by creating a masterpiece designed to transcend politics. Written during his exile, Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” was an epic tale to unite Italy under a common language, to bring together Christendom’s classical roots with its contemporary saints, and so to join souls, past and present, on their common journey to the Lord.

Words were the bricks and mortar of his opus. The fragmented Latin-derived dialects reflected the factions and tribes that sprang up after the fall of the Roman Empire. Tainted with Arabic in Sicily and with Greek in Venice, dialects formed verbal fences limiting communication. Thanks to his wide-ranging experience of poetry throughout the Italian peninsula, Dante could select the perfect words to craft his verses.

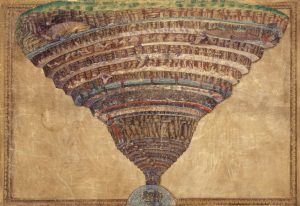

His poetry painted pictures and stimulated the senses. One can almost hear the sighing of the unbaptized in limbo or feel the cold of the frozen Lake Cocytus where traitors are imprisoned. Anticipating St. Ignatius’ composition of place in the spiritual exercises, Dante awakens the senses during his extraordinary voyage through hell, purgatory, and heaven.

His literary images are knit together by Dante’s invention of “terza rima” (“third rhyme”), an interlocking rhyme system that propels the story stanza by stanza. Dante’s epic took words, and instead of using them to divide and wound, he employed them as a means to unify a divided people. The poem offered readers the chance to revel in the pleasure of speech, an anomaly for today’s world where communicating can seem more like stepping into a minefield.

“The Divine Comedy” deftly melded pagan references with the most recent Christian theology, creating a blend of the finest Mediterranean vintages. Mythological creatures populate the “Inferno,” while Emperor Trajan exemplifies humility in the “Purgatorio.” Virgil, Augustan poet par excellence, serves as Dante’s guide, though the final steps in the “Paradiso” are led by St. Bernard.

Dante knew well the murderous persecutions inflicted on Christians by the Ancient Romans, yet instead of “canceling” the past, he transformed it. “The Divine Comedy” is an illustration of St. Paul’s exhortation to the Philippians, “whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable — if anything is excellent or praiseworthy — think about such things.”

It took the best of antiquity, emptied it of error, and converted its beauty to promote the true and good. While readers enjoy “The Divine Comedy” and its vignettes of retribution, it is also a story of redemption, including a reconciliation between Christendom and its pagan ancestors.

In the present age, so quick to sacrifice European philosophy, history, and literature on the altar of political correctness, it grows increasingly difficult for people to comprehend and appreciate Dante’s art, steeped in a Christian thought.

“The Divine Comedy” is an intensely personal quest, where Dante reveals his own sins and weaknesses. It is simultaneously a metaphor for humanity’s universal journey toward its Creator, described in the last line of the comedy as “the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.” Love is the guiding force of the work, personified in the beautiful Beatrice whom Dante admired from afar. It is she who sends Virgil to rescue Dante lost in sin, she who guides him through paradise.

Dante’s epic is laden with love. The “Inferno” is populated by lovers — lovers of power, of money, of self — the author even feels a twinge of pity for the adulterous love that damned Paolo and Francesca to windswept torment in hell.

Purgatory articulates the poet’s theology of love, divided into “bad love,” “too little love,” and “immoderate love,” all of which must be transformed into a pure love directed at the Lord.

The greatest modern challenge to understanding “The Divine Comedy” may be in the loss of the understanding of the word “to love.” Contemporary culture invokes love at every turn, whether for the superficial, the disordered or as a weapon against “haters,” generally described as those with differing beliefs. The divergent paths of these many “meanings” of love foment division, leaving many in the same situation as Dante at the beginning of the epic, “lost in a dark wood.”

Living in an age with awesome capabilities of communication brings responsibilities. The Year of Dante offers a remarkable opportunity to think about the privilege of literacy, the power of language for good or ill, and how to bring beauty back into our daily discourse.