Any anthology is a product of its editor’s decisions. In “100 Great Catholic Poems” (Word on Fire, $34.95), editor Sally Read has made some tough ones, and the result is inspiring. The hundred poems that made the final cut are excellent representatives of 2,000 years of glorious Catholic poetry.

Read is an award-winning poet who came to both poetry and Catholicism later in life and has a convert’s enthusiasm for each. “The truths of the faith have always been transmitted through poetry … because some things are too complex for stark prose,” she writes in the introduction.

The poems are arranged chronologically, from Mary’s “Magnificat,” recorded by St. Luke, to George Mackay Brown’s “Lux Perpetua,” published in 1996. (Read did not include any living poets: “Greatness needs to stand some test of time.”)

Between these two markers lies a bountiful collection of well-known, lesser-known, and little-known-but-superb poems by 83 poets. Converts make up more than a third of the poets.

Every Catholic will recognize at least a few of the poems. Some poems are so perfect, and so Catholic, that they’ll appear on every list, every time: Hopkins’ “God’s Grandeur”; Thompson’s “The Hound of Heaven.”

Much of the pleasure of this anthology, however, is in discovering or rediscovering transcendent poems by lesser-known poets, and by personages known for talents or traits other than poetry. Think Michelangelo, who left us more than 300 poems.

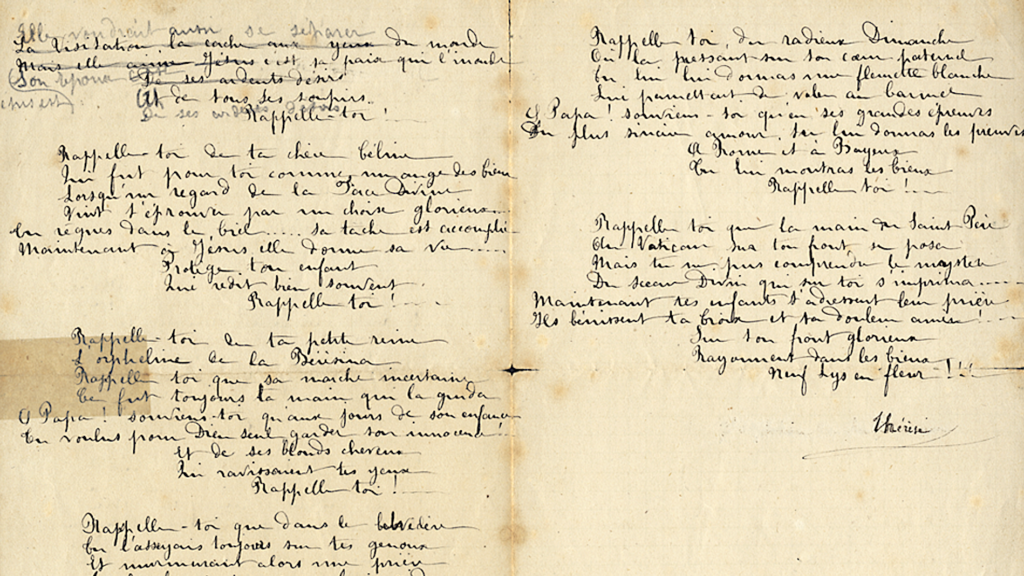

A number of the minor poets whose great poems show up here went on to become saints by one route or another. St. Thérèse of Lisieux, St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, and St. Pope John Paul II are all represented. They didn’t spend their lives writing poetry, but they wrote at least one great poem.

So what is a “great Catholic poem”? It’s complicated. Forget about defining great: in our current millennium, poets can’t even agree on what a poem is. And for a poem to be Catholic does not mean that it must be written by a Catholic or have a Catholic subject. Shakespeare, depending on who you believe he really was, may not have been a Catholic, but his writing is as Catholic as can be. “One Flesh,” by the devoutly Catholic Elizabeth Jennings, is “about” an older married couple sleeping in separate beds — surely not a standard Catholic subject.

It’s complicated. Read’s fun 24-page introduction tells us her thinking as she carved the shape of the anthology. (She had begun to see herself as “a sculptor with a modeling knife.”) A procedure is not a definition, but a roomful of books scrupulously defining those three words would still inevitably disappoint — or enrage — many people.

Read was searching for the essence of “great Catholic poetry.” For her, the essence turned out to be something she calls a “Catholic mindset” or “Catholic heart,” which, she says, “often seemed to hinge on a physicality that could only ever be found in the poetry of a faith that believes that its adherents take God in their mouths.” Now we’re getting somewhere. Catholicism is above all things incarnational.

She also looked for poems that bear witness to the major tenets of the faith — again, not necessarily in their subject, but certainly in their attitude toward or approach to reality on both sides of the veil.

At the end of the introduction, Read asks us to let the 100 poems themselves define great Catholic poetry for us. It’s cheating — but it’s necessary, and it works. This is not math. Poetry is made of gray areas skillfully presented for consideration. After spending time with these poems, we do have a strong sense of that definition — and possibly a more justifiable sense than we would get from that roomful of books.

This anthology offers even more than sublime poetic content, however. Read’s introductions to each poem are several pages long, deep and beautifully wrought. Whether a poem is an old friend or a new discovery, the reader will learn something from her introduction. Here’s just one example: “I Cannot Dance, O Lord,” written by Mechthild of Magdeburg in the 13th century.

I Cannot Dance, O Lord

“I cannot dance, O Lord,

Unless You lead me.

If You wish me to leap joyfully,

Let me see You dance and sing —

Then I will leap into Love —

And from Love into Knowledge,

And from Knowledge into the Harvest,

The sweetest Fruit beyond human sense.

There I will stay with you, whirling.”

This is an excerpt from Read’s introduction of Mechthild’s poem:

“The fact that Mechthild urges God to lead her in such a dance is a sign that she wants him to be joyful too — and in this dynamic she is living the Catholic calling to love God like his bride (2 Corinthians 11:2). Moreover, she wants her exuberance only to be a reflection of his glee. Like Mary, she wants to be a mirror of him. He needs to lead the dance.

“As we read the boldness of her lines, we might imagine how she shocked the medieval establishment. … This is not a poem about a one-off state of rapture, but rather the ceaseless prayer and union with God that Mechthild was striving for, a state that requires steady trust and abandonment. It is about having the bravery to step into those flames of joy.”

Like any good poem, Mechthild’s can stand on its own. A careful reader will come to understand her meaning. Read’s 100 commentaries simply offer a helping hand — perhaps a bit of history, pertinent biography, or context — for interested readers.

There are other Catholic poetry anthologies on the market, each with its own scope and purpose. The scope of “100 Great Catholic Poems” is the 2,000 years of Christendom, and its purpose is to lead readers to greater holiness through the pleasure of great poetry. Sally Read, an excellent Catholic poet herself, has created an anthology that fulfills its purpose.