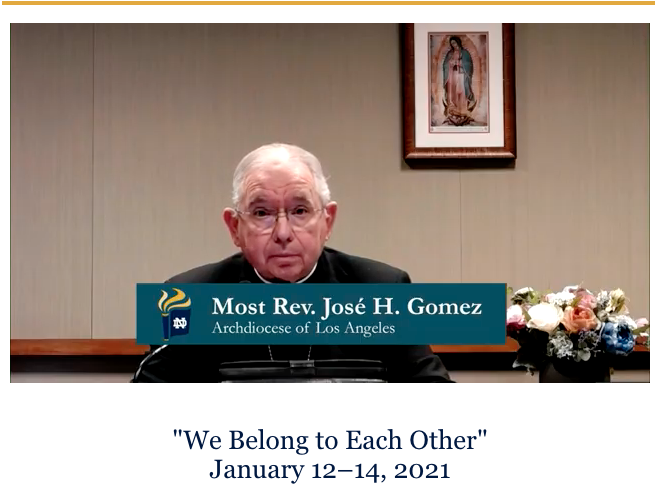

On Jan. 12, Archbishop Gomez delivered the keynote address for the annual conference of the University of Notre Dame’s De Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture on the theme, “We Belong to One Another.”

It is very good to be with all of you tonight, even though unfortunately we are still forced these days to gather “virtually.”

In the spirit of your conference theme, I want to start my talk tonight by telling one of my favorite stories from the life of St. Mother Teresa. It goes like this:

One day, Mother Teresa found an old and very sick woman lying on the streets of Calcutta. The woman was covered in open sores; she was in a lot of pain, and many of her wounds were infected. Mother Teresa took her in and started cleaning her up.

The whole time, this woman was yelling at her, cursing at her. At one point the woman cried out: “Why are you doing this? People don’t do things like this. Who taught you?”

Mother Teresa replied simply, “My God taught me.”

Now, that made the woman calm down a little. So, she asked, “Who is this God?”

And Mother Teresa replied, again very simply: “You know my God. My God is called Love.”

I’m sure some of you have heard this story before. It teaches a beautiful lesson about compassion and respect for human dignity.

But I wanted to share this little story tonight because it gets to the heart of our responsibilities as Christians. This story tells us two important truths. It tells us who God is and it tells us who we are as human beings.

As Christians, we worship a God who has revealed himself as Love. And as Christians, we know that human beings are made in the image of this God, in the image of Love.

We are created out of love. And we are made to love. To love as Jesus loved, and as Mother Teresa and the saints love.

Whenever I hear this story, I am reminded of that beautiful saying from St. Augustine, “If you see love, you see the Trinity.” This is the truth about God, the truth about the human person.

I have been working for immigration reform and advocating for migrants and refugees for at least 20 years now. And I have come to see that questions like “What do we owe to the migrant?” are really part of these deeper questions about God and the human person.

Unless we know these truths, we cannot understand our Christian commitments — for immigrants and refugees, for the poor, the unborn, the imprisoned, the sick, the environment. Unless we know these truths, we cannot understand how to create a society that will be good for human beings.

Right now in the West, nations, corporations, international agencies, and other actors are trying to build a global economic and political order that does not need to rely on beliefs about God or traditional religious values and principles.

But what we are finding is that when we lose this Judeo-Christian idea — of a God who creates the human person in his image — then we lose the basis for all the noble principles and goals that we have in our society.

Without belief in a Creator who establishes values, we have no authority higher than our own politics and procedures. We are left with no solid foundation for our commitments to human dignity, freedom, equality, and fraternity.

To put our challenge in its simplest terms: unless we believe that we have a Father in heaven, there’s no necessary reason for us treat one another as brothers and sisters on earth.

That is one of the underlying concerns in Pope Francis’s latest encyclical, “Fratelli Tutti.”

For me, I read this encyclical as a kind of “missionary” work. The pope is writing to evangelize. He’s writing to explain the moral implications of the Gospel for a world that has become aggressively secularized.

At the heart of the Holy Father’s appeal is that simple, beautiful truth that we have been talking about. That God is Love. That he is our Father and we are his children. That he calls us to form one human family and to live together in love as brothers and sisters.

As we know, the condition of migrants and refugees has been one of the key moral concerns of this pontificate.

And it is true: forced migration, mass movements of populations, is one of the signs of our times. Not since World War II has the world faced this kind of refugee crisis.

The United Nations says that right now there are roughly 80 million people in the world who have been “forcibly displaced.” That’s a polite expression for a violent reality.

These are people who’ve been driven from their homes. By war and persecution, by social chaos and economic distress.

They are living on the run; they are exploited by human smugglers and some of them are being sold into slavery.

About half of these 80 million are children.

And of course, their living conditions have been made even more desperate now, because of the pandemic and the closing of borders.

But the global refugee crisis — like so many of the troubles in the world — is more than a failure of politics or diplomacy. It’s a failure of human fraternity and solidarity. It’s a failure of love.

At Lampedusa in the Mediterranean, where so many Africans have suffered and died trying to get to Europe, Pope Francis said:

“Today no one in our world feels responsible; we have lost a sense of responsibility for our brothers and sisters. … In this globalized world, we have fallen into globalized indifference.”

And that is our challenge and our mission as Christians, as the Church.

A nation’s response to the demands of refugees and migrants requires prudential judgments about such things as national identity and national security, the effects on the economy and the fabric of society. These considerations are spelled out in the Church’s social doctrine.

But there is no question what God expects from each of us, as followers of Jesus Christ. What do we owe to migrants and refugees? We owe them our love.

Love means remembering that they are souls, not statistics. They are men and women and children with dreams and hopes, no different than you.

Every immigrant and refugee is a child of God, made in his image. Every one of them has rights and dignity that can never be denied.

And that’s true whether they are in this country legally or not; and that’s true whether they’re eligible for asylum under our laws or not.

We are all brothers and sisters, and we need to treat others as we want to be treated. As faithful citizens, we need to work to ensure that our nation is welcoming and generous, that we never close our hearts or turn our backs on people in need.

But my friends, in my opinion we have an even more urgent duty in this moment.

As we have been discussing, our society has lost its bearings.

We are living in an aggressively secular society that has forgotten the truth about God and the truth about the human person.

This crisis of truth is the root cause of the pain and hardship that we find in so many of our neighbors’ lives. It is the cause of many injustices in our society.

You and I, as Christians, we know the truth, my friends.

We have an urgent duty in this moment to bear witness to the truth — especially in light of the violence last week at our nation’s Capitol, and the deep polarization and divisions in our country.

We need to tell our neighbors about the God who is love.

We need to tell them the good news that we are all children of God, that there is a greatness to human life. That every one of us is created in God’s image, endowed with God-given rights and responsibilities, and called to a transcendent destiny.

This beautiful truth about God and the human person is the key to healing and reconciliation, it’s the way forward, the way we can come together as one nation under God.

As St. Mother Teresa taught us, our God is called Love. And he calls us to love.

By our love — by how we serve our neighbors, by how we care for one another, especially the weak and vulnerable — we can change our country and we can change the world. We can help our neighbors to know this God, and to know his love.

Thank you for listening, my friends, I look forward to our conversation.