Sister Anne Flanagan is devoted to sharing God’s love online — where she’s better known as @nunblogger of #MediaNuns — and to making spiritual reparation for the harm done through misuse of social media; a harm, the religious sister believes, that poses a serious risk for us all, her fellow Catholics included.

“We’ve lost the general sense that there are human beings on the other side of my words,” said Sister Flanagan. “We aren’t treating people as bearers of the image of God, but as bearers of an opinion that we dislike and even ridicule.

“A sarcastic or belittling response may garner us a bunch of likes, but it can crush a soul.”

Her community, the Daughters of St. Paul, was founded to evangelize through communications media in 1915 by running a village printing press. By 1923, its dual mission included “reparation for error and scandal spread through the world by the misuse of communications media.”

If the need for prayer and good works to counterbalance media-inflicted damage was apparent then, it is urgent now. Many Catholic communications professionals are discussing ethical questions raised in the new hit Netflix documentary “The Social Dilemma.”

It features former executives from companies including Facebook and Google, who warn that social media is engineered to produce addiction, isolation, polarization, and hostility.

Meanwhile, Pope Francis has proven to be a megaforce for the gospel on social media, with more than 26 million followers on Twitter and some 7 million on Instagram.

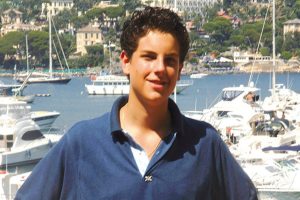

Last month, he beatified the Church’s first potential saint of the digital age. Bl. Carlo Acutis, a 15-year-old computer whiz when he died in 2006, had a Playstation and enjoyed Pokémon. He combined his talents with his devotion to the Eucharist to create a website cataloguing the various eucharistic miracles around the world.

In 2020, the internet — particularly social media such as Facebook Live and YouTube — has been crucial to holding parish communities together during the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdowns.

“In the time of the pandemic, it’s hard not to engage in social media,” said Clarissa Aljentera, an author and pastoral minister in the Archdiocese of Chicago who has run church-related social media accounts.

The challenge is to make parishes more inviting than pages.

When the lockdowns lift, “I think it calls even more so for us as Church to be welcoming and inviting,” Aljentera said. “As much as we invite people to engage online, we also have to remind them to log off and find other ways to restore and connect.”

David Gibson, director of the Center on Religion and Culture at Fordham University, considers social media a blessing.

He finds “people asking for prayer, people educating us. Somebody may put out an incorrect or uncharitable tweet or post, but someone else can go back and correct it. There is a real benefit to social media. We can’t simply run away from it.”

Traditional spiritual disciplines, such as discernment and prudence, are important online, he said.

“Part of the addiction of social media is that it makes us so reactive,” Gibson said. He advises taking time to pray about whether it is wise, helpful, and charitable to share or respond to a disturbing post.

“Take a digital Sabbath,” he said, acknowledging how difficult that is. “I have a teenage daughter and I yell at her all the time about screen time, but I’m the worst offender.”

Research done by Maryanne Wolf, director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at UCLA, has shown that extensive screen time erodes brain circuitry, undermining people’s ability to analyze what they read.

Screen readers can’t keep up with cascading information and are constantly distracted by competing content. That leads to skimming, which misses nuances and hinders the inferences and associations necessary for critical analysis.

“If you skim, you short-circuit,” said Wolf, a lifelong Catholic whom Pope Francis appointed in October to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, roughly the Vatican equivalent of an advisory council.

The ethical implications are enormous, because deep reading is crucial for developing empathy, she said. The capacity for empathy grows as readers imagine what it is like to be someone else.

“In the words of one psychologist, books provide a moral laboratory for our children,” she said.

A faith rooted in “the Word” must take that concern seriously, she said.

“Language itself is the human drive to articulate the ineffable, the impossible to put into words, the concepts that go beyond language. Language is our best vehicle for that . . . and it’s that quality underlying language that goes missing on the screen.”

Erick Marquez, a 24-year-old Catholic missionary to urban youth for the Culture Project in Pittsburgh, said young people often evaluate themselves and others by their social media standing. Teens interrogate Culture Project missionaries about their follower statistics.

“We talk about where we find our worth. Are we placing it in the number of followers we have?” he said.

“When you bring it to their attention, it’s like their first encounter with truth. You can read it on their faces as they start to ask themselves, ‘Is this what I’m doing?’ ”

The missionaries lead conversations about why “likes” make people feel good, “but it’s not enough,” Marquez said. “Because it’s not actual interaction. It’s not human. It’s not communal. It will never replace interpersonal relationships and good conversations with friends and family. It isn’t the space where authentic relationship is found, which is in a relationship with Jesus Christ.”

At the same time, social media serves a good purpose when people use it to support one another or to stay in touch with real friends and family, like “a springboard for the in-person, authentic relationships which we desire,” Marquez said.

This summer one of the biggest names in Catholic media, Auxiliary Bishop Robert E. Barron of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, called out Catholics behaving badly online after self-proclaimed defenders of the faith overwhelmed his Word on Fire pages with foul comments.

“I asked, do you realize how inimical to evangelization this is, when people come to our website out of a sincere curiosity to find out what the Catholic Church is about, and what they see is the most obnoxious vitriol you could imagine? You are actually driving people away from the Church,” he recalled.

Catholics seeking online information about the Catholic faith should consult sites with a variety of perspectives, he said, citing St. Thomas Aquinas’ wide reading and his charity when dismissing unorthodox views.

“What is not helpful is locking myself into one intellectual silo and hurling invective at my enemies,” Bishop Barron said.

Despite those concerns, Bishop Barron believes “the Church would be derelict if it did not use social media.”

Before social media “we’d say, ‘Let’s start a program in our parish and hope people will come.’ Most people we are engaging [through Word on Fire] would never come to our program. It gives us a way to move into their world,” he said.

At least one Christian group eschews social media, with concerns paralleling those raised in “The Social Dilemma.” The Amish engage in community discernment of how any innovation might affect their spiritual, communal, and family life.

They ask, “Is it something that brings us together or pulls us apart?” said Steve Nolt, senior scholar at the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania.

Initially, many Amish favored cellphones for enabling communication with family working construction at sites without landlines. That changed with smartphones.

In 2014, an Amish businessman who had given up his cellphone told a gathering that a smartphone “makes the development of compulsive behaviors and bad habits so, so very much easier and much more likely,” according to Nolt’s account.

“It would be easy now to just say to you, ‘Keep the Lord in your heart and make good choices and all will be well,’ but the issue goes deeper,” he said. He outlined the Amish understanding that community is essential because individuals don’t make good moral decisions on their own.

“One of the marks of America is its individualism. . . . Yet, the Bible was written to communities about communities,” he continued. “It is one of the oldest schemes of . . . Satan to isolate people [because] he knows that isolation will cut us off from the wisdom that multiple perspectives bring.”

Accountability is necessary for Christian use of social media, said Sister Flanagan. She has occasionally deleted her own posts after another sister pointed out a tone unworthy of a follower of Christ.

“We have to be open to fraternal correction,” she said.

Catholics should recall that “rash judgment is a sin against the Eighth Commandment,” she said. “We can sin against truth very easily on the internet. Those sins should be brought to confession. They can be grave sins.”

She is particularly disturbed by the self-contradictory witness of Catholics who denounce Pope Francis as untrustworthy or even heretical.

“Who are you to make that judgment?” she asked, her voice dropping to a whisper. “Excuse me, but he’s the only person on earth who has a divine guarantee that he’s got the keys to the kingdom, and the gates of hell will not prevail against a Church under his authority. So tread lightly.”

In 2012 Bishop Paul Tighe, currently secretary of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Culture, was on the social communications team that helped Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI launch the first papal tweet. Within an hour, @Pontifex had 250,000 followers.

Although the Vatican has issued many documents on communications, the photo of the elderly pope hitting send, “got more attention on the issue than any of the theoretical statements that had ever been made,” Bishop Tighe said.

“Some people would have the Church stay out of the social media arena because it is so dark and negative. I believe that people of goodwill will want to use social media for human unity. If they abandon the field, then it will indeed become something irredeemably negative.”

While his former Vatican assignment explored methods of communication, his current one promotes reflection on the cultural impact of communication. Social media can aid Pope Francis’ call for a “culture of encounter” through its capacity to create conversations, but the essence of encounter is spiritual.

“We can’t be looking for technological fixes in this area,” Bishop Tighe said of digital toxicity. “Ultimately, good communication is a human, not a technological, achievement.”

When the Vatican held a conference for Catholic bloggers, “we deliberately made a choice not to filter people out” ideologically, he said.

As participants talked, hostility faded. After one of the more conservative bloggers revealed an illness, many of her fervent critics “expressed sympathy and hope for her. That’s a human factor we need to create,” Bishop Tighe said.

A culture of encounter is “not just a strategy for communication,” he said. “It comes down to almost an inner conversion.”

When Catholics “find ourselves in the company of people with whom we have a lot of differences, we need to try to speak together and learn from them.”

That’s part of the mission at Georgetown University’s Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, where Kim Daniels is associate director. A member of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Communications, she helps to organize panels of Catholics with diverging viewpoints.

“We work hard to build bridges across ideological divisions,” she said.

She finds many healthy conversations on social media.

“It’s exposed me to the work of scholars and writers and others who would not otherwise have crossed my path,” she said. “It can build some sense of community that may not be deep and personal, but it can connect people across divisions and demographics when used at its best. It gives a real tool to those who are poor and suffering to bring their needs before others.”

But when users seek information only from sites that confirm their own biases, “social media can drive the amplification of crises, erosion of trust and the undermining of authority,” she said.

The bottom line for Catholics on social media is, Daniels said, “Remember to love your neighbor and to bring honesty, charity, and forgiveness to online conversations.”