In that brief intermezzo over the summer between what turned out to be the first and second great surges of the COVID-19 pandemic, Pope Francis held a series of appropriately socially distanced, “virtual” conversations with his premier English-language explicator about what he believes needs to be done for the world to be better than it was before the crisis.

Through conversations held on the phone, through voice recordings and via email, Francis answered questions posed to him by British biographer Austen Ivereigh on a wide range of issues, including the death of George Floyd; clerical sexual abuse; the toppling of statues in an effort to reshape perceptions of history; protests against government coronavirus restrictions; persecuted minorities such as Christians, Yazidi, Rohingya and Uighurs; migrants and refugees; and, though the book notes “many will be irritated to hear a pope return to the topic,” Francis discussed abortion at length too.

“I cannot stay silent over 30 to 40 million unborn lives cast aside every year through abortion,” the pope said. “It is painful to behold how in many regions that see themselves as developed the practice is often urged because the children to come are disabled, or unplanned. Human life is never a burden.”

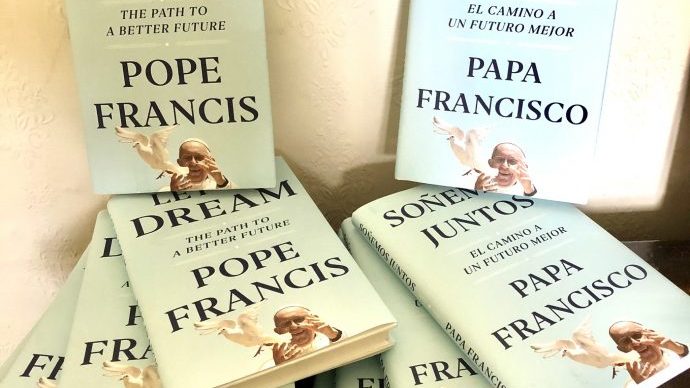

The pope’s comments are included in an interview book he authored with Ivereigh, titled Let us Dream, which will hit bookstores and online shops Dec. 1. Crux, along with other news outlets, received an advance copy.

On abuse, both sexual and abuses of power, Francis noted that social distancing has made some potential victims more susceptible to online grooming and other abuses which, as a community, “we should be watching out for and reporting.”

“In these past years, thank God, we have seen a particular awareness of these issues,” he said. “The culture of abuse, whether sexual or of power and conscience, began to be dismantled first by victims and their families, who in spite of their pain, were able to carry through their struggle for justice and help alert and heal society of this perversity.”

Francis added he “will not tire of saying with sorrow and shame, these abuses were also committed by some members of the Church.”

“In these past years we have taken important steps to stamp out abuse and to engender a culture of care to respond swiftly to accusations,” the pope said. “Creating that culture will take time, but it is an unavoidable commitment which we must make every effort to insist on.”

Society too, Francis argued, has awaken against abuse, either through the #MeToo movement, or the many scandals “around powerful politicians, media moguls and businessmen.”

“A mindset has been exposed: if they can have all they want, when they want it, why not take advantage sexually of vulnerable young women? The sins of the powerful are almost always sins of entitlement, committed by people whose lack of shame and brazen arrogance are stunning.”

The pope argued that the root of the sin of abuse is “failing to respect the value of a person.” Here, Francis connects the dots to “another abuse of power” that took place this summer, “the horrendous police killing of George Floyd” that triggered protests against racism around the world.

After underlining the need to uproot all kinds of abuse, the pontiff warned that such awakenings of consciousness, “like all good things,” can be manipulated and commercialized. This is not, he said, an attempt to cast doubt on the many brave attempts to uncover corruption and give victims a voice, but as a warning that amidst good, there can be bad.

“I find it sad that there are lawyers who take advantage of abuse victims, not wanting to help and defend them but to profit from them,” he said.

A crisp 150 pages long, the book presents Francis’s overview of the world’s situation. It’s structured in terms of the “See/Judge/Act” method pioneered by the late Belgian Cardinal Joseph-Léon Cardijn, who died in 1967.

Ivereigh’s own voice is largely absent from the book except for a postscript, where he shares some insights on how the book came to be. He says it took shape in his mind during Francis’ historic Urbi et Orbi blessing in late March, when the first wave of the pandemic had forced most of Europe into lockdown.

Asked by Crux if Francis had brought up some of this summer’s events himself, or if Ivereigh had in his questions, the British author of The Great Reformer and the Good Shepherd, said “I asked him about the Black Lives Matters protests and other things, but a lot of what’s in the book he brought up without my prompting.”

Ivereigh said he largely communicated with Francis through letters exchanged via email, as well as voice recordings by the pope answering to Ivereigh’s questions. However, the pope also suggested documents and texts for the British biographer to include in the initial drafts for him to review and correct.

“The object of the book’s first part was for the pope to look at all that was happening in the world with the eyes of the Good Shepherd, so that the reader could see the world through him — with particular attention, of course, to the margins, places of pain and suffering and spiritual movements,” Ivereigh told Crux.

The two never met during the writing process, though Ivereigh presented the pope with the final version headed for print Sept. 1 when he was in Rome for other matters.

The plethora of topics the two discussed in the book, written simultaneously in Spanish and English, includes why Pope Francis thinks women during the COVID-19 crisis have proved better leaders, and why female economists offer a blueprint for the new kind of economy the world needs; why change can only come from the margins of society and a politics centered on fraternity and solidarity; why the Pope favors a universal basic income, and strong curbs on a neo-liberal market economy to enable access to work, greater equality, and ecological recovery; and the need for a new kind of politics beyond managerialism and populism, rooted in service of society and the common good.

Among other points, Francis also reiterates his familiar criticism of movements within the Church that he calls “too rigid.” Through out the history of the Church, Francis said, “groups that have ended up in heresy because of this temptation to a pride that made them feel superior to the Body of Christ.”

“Rigidity is the sign of the bad spirit concealing something,” he says in the book. “What is hidden might not be revealed for a long time, until some scandal erupts.” There have been a fair share of these groups in recent years, “movements almost always marked by their rigidity and authoritarianism,” that presented themselves as restorers of Church doctrine, but “sooner or later there’ll be some shocking revelation involving sex, money, or mind control.”

As he’s said many times since the pandemic began, the pope also argues that in moments of crisis, one gets both the good and the bad, with people revealing themselves as they are: “Some spend themselves in the service of those in need, and some get rich off other people’s need. Some move out to meet others—in new and creative ways, without leaving their houses—while some retreat behind defensive armor. The state of our hearts is exposed.”

Francis also writes that it’s not only individuals who are tested by crisis such as this one, but also entire peoples, including governments that have had to choose in the pandemic.

“What matters more: to take care of people or keep the financial system going? Do we look after people, or sacrifice them for the sake of the stock market? Do we put the machinery of wealth on hold, knowing people will suffer, yet that way we save lives?” he said.

Though he didn’t single out any country, the pope says some governments chose to protect the economy first and thereby “mortgaged their people.”

Yet COVID-19 is far from being the only “sword” humanity faces today: this crisis “may seem special because it affects most of humankind,” yet it’s only special because it’s visible. Thousands of other crises are “just as dire,” but far enough that “we can act as if they don’t exist.”

“Think, for example, of the wars scattered across different parts of the world; of the production and trade in weapons; of the hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing poverty, hunger, and lack of opportunity; of climate change,” he argued. “But like the COVID crisis, they affect the whole of humanity. Just look at the figures, what a nation spends on weapons, and your blood runs cold. Then compare those figures with UNICEF’s statistics on how many children lack schooling and go to bed hungry, and you realize who pays the price for arms spending.”

Francis supports his comparison of COVID-19 with others crises statistically, noting that 3.7 million people died of hunger in the first four months of 2020.

“How will we deal with the hidden pandemics of this world, this world, the pandemics of hunger and violence and climate change?” he asks.

Throughout the book, he gives several possible answers, including this one: “This is a moment to dream big, to rethink our priorities—what we value, what we want, what we seek—and to commit to act in our daily life on what we have dreamed of.”

“Let us dare to dream. God asks us to dare to create something new. We cannot return to the false securities of the political and economic systems we had before the crisis,” he said. “We need to slow down, take stock, and design better ways of living together on this earth.”