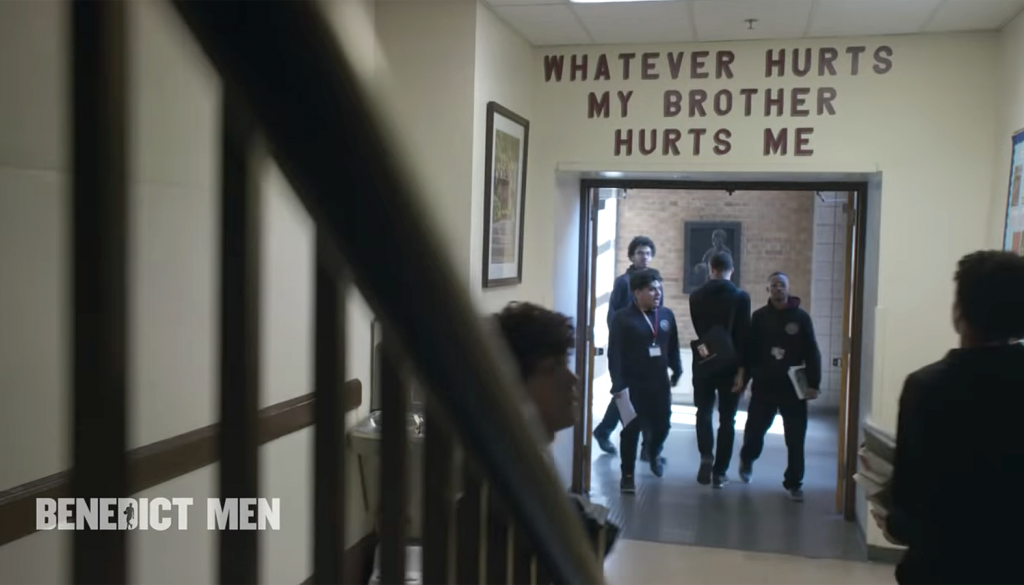

Above the doorway leading out of a high school stairwell, a collection of bold, dark letters spell out the following statement: “Whatever hurts my brother hurts me.” Such is the motto of St. Benedict’s Preparatory School in Newark, New Jersey, the focus of Quibi’s new documentary miniseries, “Benedict Men.”

At this all-boys school, which has a particular commitment to supporting young men of color and from disadvantaged backgrounds, leaders stress the importance of community. Students gather in the gym for a daily convocation, where they throw their arms around one another and sway as they sing a hymn together. In that same gym, one of the state’s top high school basketball teams takes the court every day.

Produced by basketball star Stephen Curry, the docuseries follows St. Benedict’s team through their 2019 season as they strive to take home another state championship.

As Curry explains throughout the film, the goal of “Benedict Men” is to examine how the school’s unique mission influences the team’s response to the pressures of high-ranking high school basketball, a world in which, as Curry puts it, players are told that “your buckets are more important than your brothers.”

Indeed, St. Benedict’s philosophy of brotherhood clashes with the highly competitive culture surrounding the sport. At any game, college recruiters could be eyeing a player, making individual performance a high priority. Moreover, for those lacking the financial means to pay for higher education, the pressure to get an athletic scholarship weighs even more heavily upon them.

Can St. Benedict’s overcome this tension between camaraderie and competition? As the series progresses, we find that the answer, unfortunately, is no.

Despite the school’s inspiring mission, faculty and players send contradictory messages through their words and actions on and off the court.

In one episode, headmaster Father Edwin Leahy, OSB, decries the idolization of basketball. “They have a better chance of being a neurosurgeon than they do of being a professional basketball player,” he states. Later on, other faculty members explain St. Benedict’s high academic standards and stress that student athletics is no excuse for poor grades.

And yet, the players receive hardly any other motivation from their coaches, parents, and even Father Leahy himself, except the power of their athletic performance and scholarship potential. None of them seem to have any future in mind except a spot on a Division I team followed by the NBA, and no one seems to communicate to them the importance of success outside the world of basketball.

When one player who struggles academically has a meeting with faculty and family members, we learn that his only concern is basketball. If given the choice, he would transfer to a school where he could get by with poor grades and just focus on playing. As far as we can see on camera, no one in the meeting objects, and no one advises that he consider the benefits and opportunities that education offers beyond basketball.

Another contrast arises within team members’ relationships with one another. When they huddle up at games, they shout “Family!” together. However, they hardly show concern for one another apart from their role on the court. We never see the players spending time together outside of practice, games, or tournament travels, and they never speak of one another as “my brother” or even as a friend. One player even admits to the camera, “I’m no Benedict man.” Their coaches sometimes mention the character qualities they admire and want to foster in their players, but more often we see them screaming profanities and demanding better results.

In light of these interactions, it’s hardly surprising that many players are perfectly willing to transfer out of St. Benedict’s if it puts them on a better path toward receiving a scholarship.

Finally, although some parents discuss the importance of being a kid and having fun in the game, most conversations prioritize winning above everything else. The satisfaction of victory and a ticket to a Division I school seems to be the only thing driving each teammate and coach.

Sadly, not one of them talks of actually liking to play basketball.

All of these contradictions make clear that practicing what one preaches is anything but easy. Even at a prestigious Catholic school that preaches brotherhood, the lure of individualistic achievement that is notorious in high school sports still looms large.

It could very well be that in telling St. Benedict’s Preparatory School’s story, Curry meant to expose the dichotomy between “me first” and “team first” basketball more than offer a solution. Either way, “Benedict Men” makes clear that the challenge of building a culture of camaraderie remains, and it’s going to take a lot more than a motto to do it.

“Benedict Men” is available for streaming on Quibi.