I am currently, much to the consternation of everyone else in my household, in the throes of an addiction to documentaries. Every streaming service seems to have a documentary category and some defect in my frontal lobe has urged me to explore them all.

Usually, it is to quell my constant fascination with the epic struggle that was World War II. I think I’ve seen just about every World War II documentary there is. If you ask my family, they’re SURE I have seen them all and more than once. I must confess, I’m a sucker for titles like “Hitler’s Secret Weapon,” “Hitler’s Secret Invasion Plan for America,” and “Hitler’s Secret Zombie Army in the Andes.”

But with an ever-expanding documentary universe before me, I have dabbled in such diverse fare as pinball machine culture, baseball card collectors, and the disastrous reign of King Charles I of England. It’s almost as if my synapses were zinging around my brain, as if they themselves were being propelled by pinball flippers.

My brain continued to fire away when I recently stumbled on yet another documentary with the enticing title: “Secret Vatican Archives.” I braced myself for some kind of DaVinci Code journey, replete with albino assassins and enough logic holes to walk Pope Innocent III’s sedan chair through. To my relief, I found instead a sober and straightforward examination of some of the most remarkable documents in the possession of the Holy See.

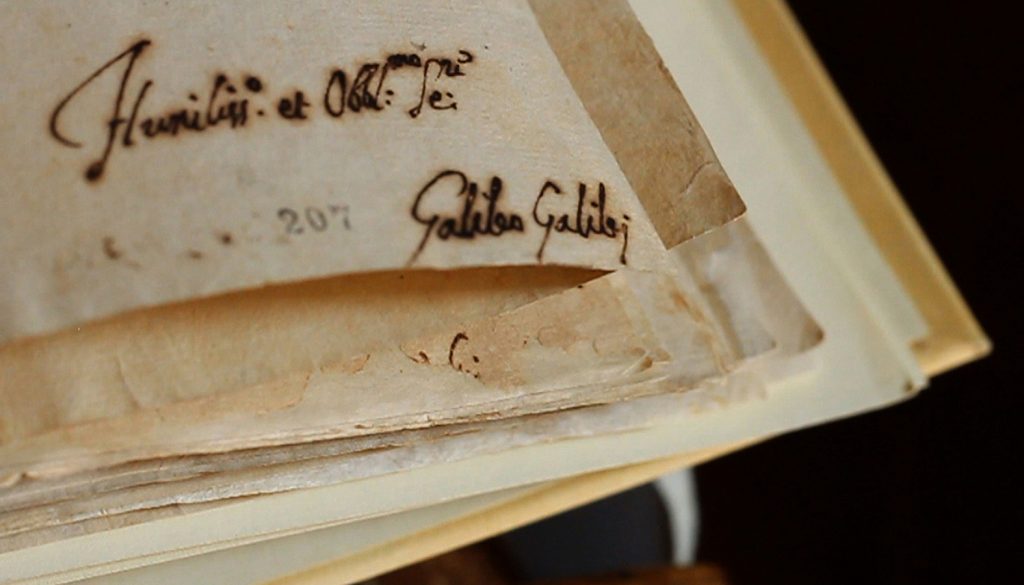

There were transcripts of trials from Galileo to the Knights Templar and even a letter from the nephew of Genghis Khan inviting the then-pope to come for a visit. They had Pope Leo X’s papal bull excommunicating the recalcitrant Martin Luther. Remarkable stuff indeed, and material witnesses to some of the most profound historical moments over the past 2,000 years.

It made me feel good to be Catholic, to be part of something that, despite scandal, sin, tragedy, and triumph, still stands just like Jesus promised.

The closest this documentary came to a paperback thriller was when an archivist showed an old wooden chair. It was not ornate or unusual in any obvious sense, other than the fact it had been used by several popes. But when it was scheduled to receive some restorative treatment from the archivists, they noticed the chair made a strange sound when it was moved. Further investigation revealed that the back of the chair, under the seat, contained a secret compartment.

When the compartment was opened, they found one of the Church’s most remarkable pieces of history. It was a document with the seals of English archbishops, English bishops, and dozens of English abbots, sent to Pope Clement VII, pleading with him to grant Henry VIII an annulment from his wife, Catherine of Aragon.

The document looks like it was produced yesterday — and you can easily imagine the shaking hands of the bishops who squished their signet rings into the wax as some of Henry VIII’s henchmen supervised approvingly.

But what will the Vatican archivist archive from 2020? Future documentary addicts may not see ancient manuscripts written in incredibly precise and orderly script, showing English bishops pressuring a pontiff to act according to the dictates of their monarch, but they may indeed see electronic versions of similar political and ecclesiastical positioning.

What became so clear to me as I watched this documentary was how similar things have always been. Whether it was English prelates, under threat of imprisonment or worse, doing the bidding of their secular master, or the nephew of the great Mongol emperor inviting the pope to visit, the emphasis remains the same. People want answers here and now, and they want the Church’s response to coincide with their own worldly agendas.

The Church was never meant to be the “English Church,” designed to meet the wants and desires of Henry Tudor, try as he did to make it so. And the “American Church” likewise does not belong to one political party or another.

I have little doubt some Vatican archivist 200 years from now will be explaining to his or her documentary-addicted audience that, due to the unbridled availability of instant communication in the early part of the 21st century, combined with ill-informed and agenda-driven individuals, there was much anger and confusion not only in the secular world but within the Church as well. And that it was a source of a lot of heat — but very little light.