Linda Dakin-Grimm grew up Catholic, first in Riverside, then in Portland, Oregon. In college, she moved away from the Catholic faith, then became an attorney, and for decades worked as a trial lawyer in high-stakes business litigation. She was a partner in a prestigious firm, with offices in LA, where she makes her home, and New York.

She was at the top of her game. She could look forward to 10 more lucrative years before retirement.

It was then that the call came. Without much understanding why, she found herself drawn back to Mass and prayer.

“Wake up!” she heard. “I took more seriously my obligation to listen. What was the Lord asking me to do at this point in my life?” She started “reading like crazy — all the Thomas Merton books. Philosophy, theology, social justice.”

The news at the time reported on the “surge” of unaccompanied minors at the southern border. She happened to be on the pastoral council at her parish.

“A guy came into our monthly meeting and said they were trying to figure out how to help these kids. And none of us knew anything. We had no idea how to help. So he just left. That made me feel uncomfortable. We’re sitting in this kind of rich white people’s parish by the beach and we don’t know a single thing about how to help these kids. That bothered me.”

Soon after, then-Msgr. (now Bishop) David O’Connell invited Dakin-Grimm to an immigration-related church event. A call went out for a cadre of pro bono lawyers to help with a program aimed at granting rights to undocumented parents of U.S. citizen children.

She started looking around and stumbled upon an organization called KIND — Kids In Need of Defense.

While still doing big trials — one in New York and another in LA — she took on a couple of pro bono kids’ cases.

“I just fell in love with the work,” she said simply. “I saw the face of Jesus in them.”

She began to educate herself in immigration law, a notoriously byzantine niche. “It was a learning curve,” she shrugs, “but that’s what lawyers do: they learn stuff.”

To Dakin-Grimm, caring for the child and the stranger seemed straight Christ-of-the-Gospels Catholicism. She was flummoxed by the fact that not all Catholics felt the same way. So while still working full time, in 2014 she enrolled in LMU and began working toward a master’s degree in theology.

The experience was invaluable. “I was learning about the real tenets of the Faith, reading Aquinas and Augustine and struggling with the question: ‘I’m Catholic. We’re a big-tent Church but what does it mean? Is Catholicism a mere social label? Is it just a cultural identity?’ ”

That question, and the children with whom she was working, became her passion.

At the end of 2015, she made a simple decision: She no longer wanted to work for money. She only wanted to do pro bono work for kids.

“I’ve never missed a meal or a vacation, so I’m no saint in that respect,” she said briskly. “I just wanted to spend what time I have left for the common good.”

Dakin-Grimm tends to galvanize those in her orbit. Her firm stuck by her, so that she’s able to continue to use their resources and their young lawyers. Marge Graf, general counsel for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, helped put out a call for translators and mentors.

Last year she did a fellowship at Harvard, enrolled in a Spanish language class with “a bunch of freshmen” on the side, and is now an Advanced Leadership Initiative Fellow, a position that allows her both to give back to the community and to continue broadening her education in the history and literature of immigration.

That original couple of cases has grown to 75. Over time, Dakin-Grimm’s work has led to working with separated families and filing class-action suits.

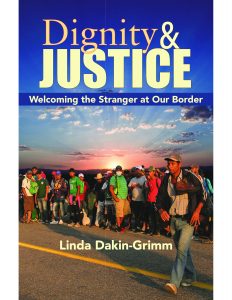

This week, her book, “Dignity and Justice: Welcoming the Stranger at Our Border,” will be published by Orbis ($24).

In it, she renders the intricacies of immigration law accessible to laypeople. She brings the situation alive with faces, names, and harrowing, gut-wrenching stories.

Dakin-Grimm is itching to spread the word about her book. “Nobody is talking about this stuff. True Catholic teaching, based on the best theologians and philosophers that the Church has yet produced.

“Augustine and after him Aquinas both said that if a human law is contrary to God’s law, we Catholics follow God’s law. We don’t say God put so-and-so in place as the president, or God put such-and-such in the U.S. Constitution so it’s OK — that is not Catholic.”

She’s especially eager to talk to Catholics as peers, from a place of respect, who are not feeling particularly welcoming to migrants but in good faith want to wrestle with these questions.

“The history of the world reveals that people have always migrated. The whole Bible is a series of migrations. If you listen to certain Catholic speakers you’d think as long as there have been humans, there’s been a border across the southern part of the U.S. But borders are a function of human law.”

The highest papal teaching document on migration, “Exsul Familia Nazarethana” (“The Family of Nazareth in Exile”), is a 1952 apostolic constitution from Pope Pius XII. In it, the pope condemned excessive nationalism: Yes, in this modern age we respect borders, to the extent that we live in the era of nation-states. But borders never trump human life.

“I would never ever have predicted that I would be a Bible-thumping fire-and-brimstone person. But read Matthew 25. ‘Did you welcome me when I was a stranger?’ The least of our brothers and sisters is Christ himself. The stakes here are life and death. This is bedrock. We’re called to ask ourselves: Do I believe in Jesus or not? Or am I just in some kind of club?”