As we ricochet between tragedy and farce in this time of pandemic, perhaps we need a bit of the gothic as well.

Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, “The Masque of the Red Death,” seems appropriate. It tells the tale of Prince Prospero, whose country is being ravaged by a hideous plague called the “Red Death.” Prospero rounds up his posse of “hale and light-hearted friends” and retreats to a remote palace to “part-ay” and “chillax” as we might explain it today.

The prince orders the doors welded shut so no one can enter or leave. Poe tells us: “With such precautions the courtiers might bid defiance to contagion. The external world could take care of itself.” As one might expect with Poe, all does not end well.

I thought of Poe’s story when reading of a recent study reporting that wealthy New Yorkers got out of town once the coronavirus (COVID-19) hit. Between March 1 and May 1, 5% of New Yorkers left the city, but 40 percent of those living in wealthy neighborhoods like the upper west and east sides fled.

While the city was ravaged by the coronavirus, those with means vamoosed to the Hamptons, letting “the external world take care of itself.”

Unlike the partygoers in Poe’s tale, the New York elite may come out of all this just fine, with both their health and their portfolios relatively unscathed. But all around them, the land of Prince Prospero has suffered a grievous wound.

The pandemic has exposed a host of our weaknesses.

It exposed our educational divide. While wealthy school districts were able to transition to remote learning with relative ease, poor schools already suffering from scarce resources were incapable of adequately teaching children whose families literally and figuratively do not have the bandwidth needed.

An estimated 42 million Americans still have little or no access to the internet. One of my daughters, who teaches English as a Second Language, estimates she is reaching only 10% of her students during this time of remote learning. Families cannot provide what they do not have, and those without fall further behind.

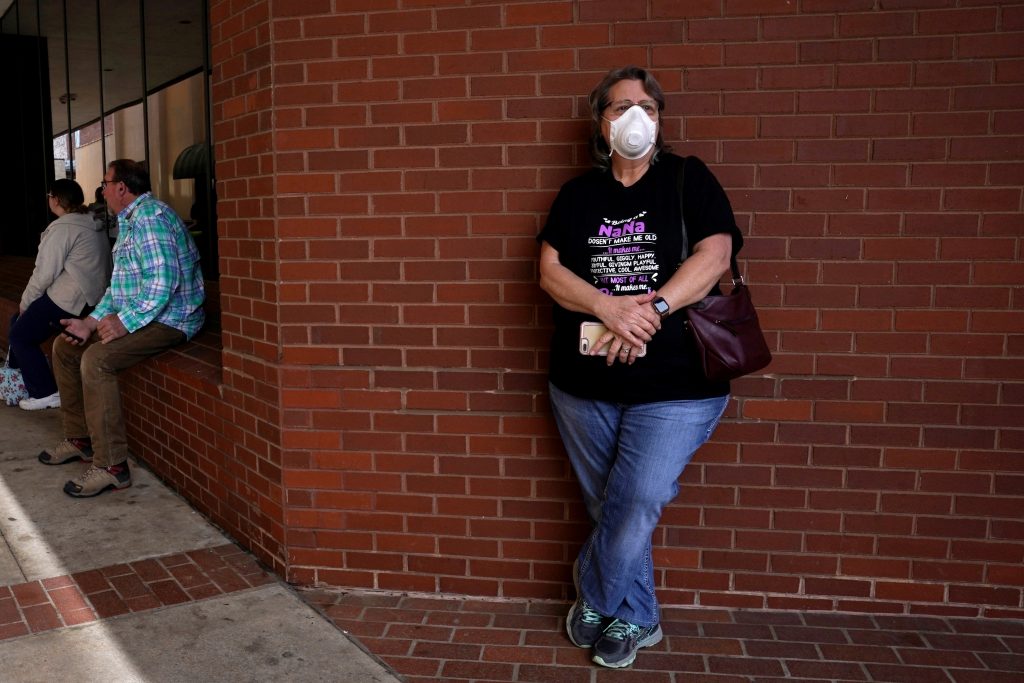

It exposed our health care divide, where millions who lost their jobs also lost their health insurance. Now rural communities, which have been suffering from a scarcity of health care resources for decades, are in the path of the pandemic. The courage of our health care workers and the prowess of our research community are being offset by a system in which our most vulnerable are left exposed outside our gates, incentivized or threatened to work even when sick.

Likewise, the pandemic has exposed our racial and age divides, with African Americans, Native Americans and Hispanics suffering disproportionately from the ravages of the virus. Our elderly citizens also have paid a higher price, as well as the often poorly paid workers who care for them.

We shall see how this all plays out, but as with other crises, those already blessed may flourish, while those with less will suffer more and the divide between them will grow. If the jobs and the tax dollars are slow to come back, the next temptation will be to “tighten belts,” code for cutting benefits and social services to further hurt those communities already most hurt by the disease.

A gloomy March 15 New York Times article predicted that the pandemic was likely to “widen the socioeconomic divides that are thought to be major drivers of right-wing populism, racial animosity and deaths of despair — those resulting from alcoholism, suicide, or drug overdoses.”

It’s a driver of left-wing populism as well. As one Italian factory worker was quoted as saying, “Who cares about the workers’ health while the rich run away?”

All of this sad chronicle is reason to hope that we do not run away from the lessons to be learned from this crisis, that we do not too quickly return to a socially dysfunctional “normal.”

What is needed instead is a new national commitment to the common good, and a rejection of the “every man for himself” ethos that has pitted states against states and communities against communities during this crisis.

Pope Francis in “The Joy of the Gospel” wrote that a commitment to the common good means “acting as committed and responsible citizens, not as a mob swayed by the powers that be.” And Catholics are called to support those programs that “best respond to the dignity of each person and the common good.”

For the pope, there is an opportunity in this tragedy: “May the difficulties of this time make us discover communion among us, the unity that is always superior to every division,” he prayed recently.

In Poe’s ending, “Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.” Our tale can have a different conclusion, but that will be an ending only we can write.