Award-winning poet Leslie Williams grew up in North Carolina, lived and worked in Washington, D.C., Seattle, and Charlottesville (where she earned a degree in English), got married, moved to Chicago, had a son, moved back to Washington, had another son, and moved to the Boston area, where she and her family have been for 15 years.

She’s been writing and doing community and church work ever since, including teaching poetry and Sunday school.

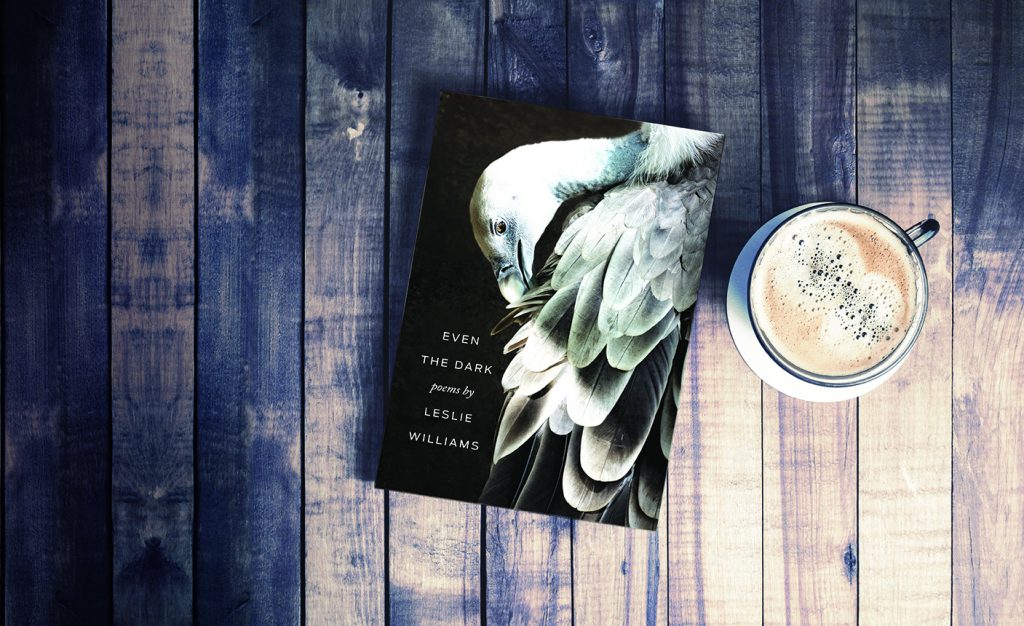

Her first book, “Success of the Seed Plants,” (Bellday Books Inc., $14) came out in 2010 and garnered the Bellday Prize. Her latest collection, “Even the Dark” (Southern Illinois University Press, $13), was co-winner of the Crab Orchard Series in Poetry Open Competition.

She has received several artist fellowships. Her poems appear widely in such magazines as “Poetry,” “Kenyon Review,” “Image,” “America,” and “The Southern Review.”

Most notably, as her website states, “she is always wondering about the divine.”

She also hosts a blog, accessible from her site, that focuses on Scripture and is called “Finding the River.”

Of “Even the Dark,” Williams says, “I worked on many of the poems for probably 15 years and they slowly came together into this book. Poems are a way of thinking through my role in the world and in others’ lives and are for me a kind of prayer and conversation with God. I also really like words and sounds and the music a poem can make.”

Williams’ poems soar, collide with reality, wonder, observe, ache. They are about the seeming paltriness and inefficacy of our love, and the way we offer it anyway, because the alternative — to withhold our love or to yield to despair — would be the one thing blacker than life, with all its suffering.

From “When Walking by Lilacs, a Burning Smell”:

“I’m overwhelmed: the sublime / perfumed featherings of lilac, never knowing what / to do for others but letting swallows make a home / here because I can spare the eaves.”/

Moments that might bypass a less keen observer crystallize as quicksilver shafts of light: shorthand messages from the world beyond. “Forgetful Green” enshrines a stab of transcendence while gathering tomatoes toward dusk from the garden: each dinner with family, in its way, a “last supper.” “In Which the Bread Crumbs Were Eaten by Birds” reflects on the memory of a childhood friend lost to suicide.

“Even the Gladioli,” “Prayer that Starts in the Eye of a Bird,” “Exile from the Kingdom of Ordinary Sight”: these are poems that grope for transcendence in the missed chance, the offer to help rebuffed, our inability to reconcile the human condition.

“Create in Me A Clean Heart, O God” includes the lines:

“When my mother was sick / I didn’t go / I rolled over in my own bed / I thought she wanted // to be alone, / alone how I like to be / to keep my misery.”/

The title is borrowed from Psalm 51, which runs in part, “O see, in guilt I was born, a sinner was I conceived.” The compact lines of Williams’ own “psalm” evoke our cognizance of original sin; our knowledge that original sin alone doesn’t absolve us; and the way our mothers both shape and wound us, sometimes forming us to be unable to show up for them just as they may have been unable to show up for us.

Our absolution, the poem nonetheless manages to suggest, consists in our longing to be better, to love more deeply, to be less afraid.

These are poems, one senses, whose seeds were sown while sitting in the bleachers at a soccer game, or standing in line at the grocery store, or nursing a child.

“If American women earned minimum wage for the unpaid work they do around the house and caring for relatives, they would have made $1.5 trillion last year,” ran a recent headline in The New York Times.

Maybe, but how do you assign a price to poems of such rare beauty, that germinated in snatched moments of silence and solitude when the poet’s husband was perhaps away at work and the kids at school?

How do you cost-benefit analyze such precious works of art that might not have come to be but for the paradox of motherhood in which the insistent desire to bring life into the world requires us in some sense to die?

From her window one morning, Williams sees a young girl in pajamas — “The parents, their only child, the apple, the amen” — pad down the driveway.

This might be the start of an idyll, except that the child is en route to another chemo treatment:

“Thinking of God’s Goodness While the Ten-Year-Old Neighbor is Suffering” reminds us that religion has no answers. Religion — our religion — patiently endures. It plods. It drags its heavy cross, broken and bleeding. It praises when there seems nothing left to praise, when we seem to be howling into the abyss.

Against the existential uncertainty that at times seems more than human beings can bear, the world has assault weapons, nuclear bombs, closed borders, surveillance.

We have St. Michael the Archangel.

The poem ends like this:

“I do / believe a sickness can be rebuked, vanish with all the darkest / days; that they could return to singing. That one day this / devastation could be shadow only, a conquering. Where even / the dark is not dark to see. My God can do this but my God / might not.”