Through March 1, the Palm Springs Museum is featuring “A Designer’s Universe,” an exhibit based on the multitalented 20th-century artist Alexander Girard (1907-1993).

As the museum points out: “Alexander Girard ... was one of the most important and prolific designers of the 20th century. He created stunning interiors for restaurants, private homes, corporate offices, and even airplanes! He created textiles, typography, and tableware. He designed exhibitions, toys, and a whole city street in Columbus, Indiana. Inspired by folk art and pop art, Girard created a bold, colorful, charismatic universe. He warmed up modernism with his whimsical, optimistic patterns and designs.”

That optimism and whimsy are on full display. The exhibition, organized by Germany’s Vitra Design Museum and accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, includes more than 400 objects: from board games and flags Girard created as a child for the imaginary Republic of Fife, to textiles, drawings, carpets, radios, restaurant ware, and folk art, much of which he collected and some of which he made himself.

Girard worked closely with the iconic mid-century design firm Herman Miller. One of his most well-known interiors, the 1957 Miller House in Columbus, Indiana, appears here in the form of a full-scale replica of its famous “conversation pit,” featuring a tomato red wrap-around-the-room sofa strewn with vividly patterned pillows.

Born in 1907 to an American mother and a French-Italian father in New York, Girard grew up in Florence, and from 1917 to 1924 attended a private boarding school in England. He earned a degree from the Architectural Association in London and there developed a lifelong attraction to the theater.

The Italian Renaissance, an influence since childhood, would also continue to inform his work.

He earned a second architectural degree in Rome, then from 1932 to 1937 lived in New York City, establishing himself as an interior designer and creating spaces and furnishings for high-end clients, including restaurants and shops. His own apartment — the exhibit includes several photos and a stunning Girard-designed clock — served for a time as his showcase.

In 1936 he married Susan Needham. The couple moved to Detroit, where Girard worked for design company Thomas A. Esling.

He met internationally known design stars Charles and Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen during that period, and in 1948 the Girards moved into a house in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, that he’d designed himself. The minimalist decor, daring for its time, to me seems sterile but would be right at home in today’s world of high-end interiors.

By 1952, the family included Marshall, a son, and daughter, Sansi.

Also that year, Girard was employed by Herman Miller to head its fabric and textile division. He teamed with George Nelson and Charles and Ray Eames to form a team whose influence is felt in design circles the world over to this day.

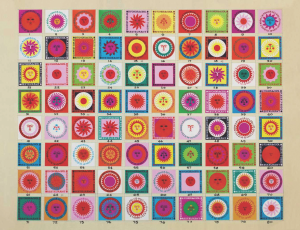

He started with geometric upholstery and drapery prints — circles, lines, triangles — and moved on to incorporate flowers, folk art and, after a trip to Mexico, colorful elements he dubbed “mexidots” and “mexistripes.” Examples of these luscious textiles abound.

Girard came to believe that design should far transcend mere function, and saw his work as a way to inject beauty, pleasure, and fun into daily activities and tasks. His attraction to folk art — especially after moving to Santa Fe later in the 1950s, when he became an inveterate collector — was based on the kinship he felt, based on those same principles, to the whimsical dolls, carved wooden figures of Christ, and handmade figures of saints emblematic of New Mexican culture.

His “Design for Matchboxes of the Restaurant La Fonda del Sol” (1960), all parrot-green, hot-pink, and saturated-turquoise suns and stars, raises the viewer’s mood a good three notches.

In 1971 he developed screen-printed graphics on fabrics for Robert Propst, inventor of the cubicle system known as Action Office, effectively adding color and warmth to an otherwise cold environment.

Well worth watching is the Braniff International video clip — “The End of the Plain Plane” was the rebranding tagline — featuring Girard-designed color scheme, airport lounges, and typeface. The flight attendant uniforms, by Emilio Pucci, included go-go boots, A-line coats, and something “a little more comfortable” in shades of apricot, almond, and pistachio.

But perhaps Girard’s most personally meaningful project consisted in his displays for the International Museum of Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he and Susan lived for decades. Through the Girard Foundation, established by the couple in 1962, the museum houses his collection of more than 100,000 pieces of toys, folk art, and textiles.

In 2015, Girard’s granddaughter Aleishall Girard Maxon, herself a designer, observed that when she was growing up, his influence was subtle. “This is something my brother and I have discussed a lot … it was a lot of subconscious infiltration, living with folk art, design, and color always surrounding us.”

In one way, Girard was to the manor born, hobnobbing with the crème de la crème of international designers, and preferring to be driven about, for example, European-style.

But at the same time, “My grandfather was very humble. He moved to Santa Fe, the middle of nowhere in the ’50s; it was a lot of dirt roads and nobody else around in terms of design. He wasn’t about notoriety, he just wanted to be close to Latin America, one of his biggest inspirations.”