Following this week’s announcement that the cause for sainthood for celebrated writer Gilbert Keith Chesterton would not go forward in his home diocese, Dale Ahlquist, an expert on the author, said this stall “points to the difficulty of getting a layperson canonized.”

Ahlquist noted one reason given for halting Chesterton’s cause was that the author, considered one of the greatest minds of the 20th century, lacked a discernible personal spirituality.

Speaking to Crux, he said that “now more than ever we need more lay saints, with clergy being under a cloud.” He said it often seems to be “easier” for priests or religious who found orders to be canonized, since the order typically promotes the person’s cause for sainthood.

However, while these individuals might have been unquestionably holy, “they’re not great inspirations for laypeople,” Ahlquist said, adding, “I hate to say it, but they are not models of spirituality for what a layperson has to go through to live the Catholic life.”

Chesterton is a “prime example of what lay spirituality is supposed to look like. I think all the evidence of his spiritual life is there,” he said, saying doubt over Chesterton’s spiritual life is a “weak reason” to halt the cause.

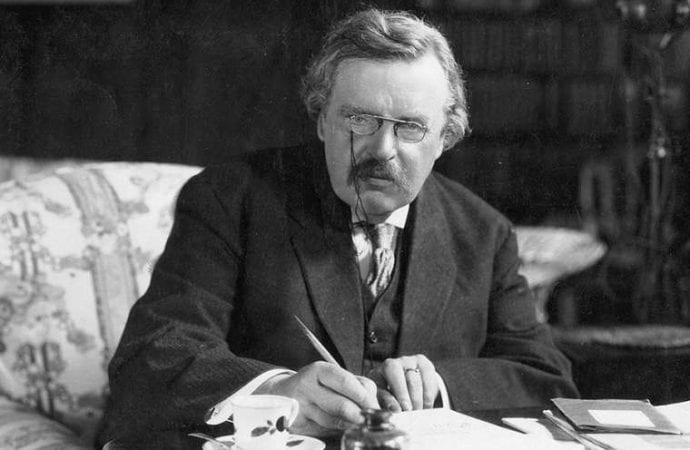

One of the best-known writers in the 20th century, Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born May 9, 1874, and died June 14, 1936. A convert to Catholicism, he was widely considered one of the most influential writers of his time.

While in the United States he is best known for his book Orthodoxy, a groundbreaking defense of Christianity, Chesterton is most famous in his homeland for his Father Brown series, a collection of short stories about a priest detective more dedicated to converting the criminals he catches than incarcerating them.

In 2013, Bishop Peter Doyle of Northampton, Chesterton’s home diocese, ordered that an initial investigation into the possibility of Chesterton’s sainthood be opened, however, he has decided not to pursue the cause, meaning the pipe-loving, cigar-smoking and general booze-enthusiast will not become a saint - at least, not yet.

Reasons given by Doyle for pulling the plug were due to what he said was a lack of “local cult,” or worship, of Chesterton on his home turf, that he could not identify a pattern of personal spirituality for Chesterton, and concerns that some of Chesterton’s writings contained anti-Semitic elements.

Ahlquist, president of the American Chesterton Society and the Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton, made the announcement at the Aug. 2 opening session of the American G.K. Chesterton Society conference happening in Kansas City this week, reading aloud a letter from Doyle.

In his comments to Crux, Ahlquist said he received the letter from Doyle in April informing him of the decision not to pursue Chesterton’s cause. While Doyle said he would not get in the way of efforts to pursue Chesterton’s cause elsewhere, Ahlquist said he took issue with Doyle’s reasons for halting the cause.

Doyle was always “very kind” throughout the process, “but he never had any enthusiasm for Chesterton,” Ahlquist said.

Ahlquist said he felt that he had addressed all of Doyle’s objections during the initial process, “so I guess the most disappointing thing would be that those three objections were made when I had already, I think, very thoroughly addressed each one of them.”

Speaking of Chesterton’s spiritual life, Ahlquist said the author didn’t speak much about his personal spiritual life, but the evidence is in his writings and was seen in his daily actions.

Citing a quote from Chesterton’s former Anglican pastor, who said that “I’m glad Chesterton is becoming Catholic, he was never a very good Anglican,” Ahlquist explained that prior to his conversion, Chesterton never went to church, but he never missed a Mass after becoming Catholic.

Ahlquist said there are also accounts of Chesterton being “emotionally shaken and sweating” before receiving communion. Asked about it, Chesterton replied that “I’m frightened of that tremendous reality,” he said.

“This shows that he had a deep and mystical understanding of the reality of the Real Presence” of Jesus in the Eucharist, Ahlquist said, recalling how Chesterton would make the sign of the cross when entering a room, or with a match as he lit up a cigar.

“It’s these little bits of evidence of his personal holiness that was evident to everyone around him, and his goodness…people were drawn to that aura about him.”

Pointing to Doyle’s criticism that there was no local cult of Chesterton in his home turf, Ahlquist said there is “a worldwide cult” to the author, and he “think(s) it’s unfair to the people who have a devotion to Chesterton all over the world to be told that unless there’s a local cult, you cannot open a cause.”

He also disputed Doyle’s claim that Chesterton’s writings contained anti-Semitic elements, saying the argument has been disproven multiple times, and that Chesterton himself “loved the Jews,” saying at one point that “the world owes God to the Jews.”

In his view, Ahlquist said he believes the concerns about anti-Semitism were not necessarily about Chesterton, but “political correctness” in terms of how certain portions of his writings are interpreted in a hyper-sensitive society.

“Unfortunately that’s the reason…for those of us who are devoted to Chesterton, we’re not only tired of that objection, because we know it’s false, but we’re also saddened by it,” Ahlquist said, noting that Doyle never called Chesterton himself anti-Semitic, but raises anti-Semitism as a sensitive issue.

“That can’t be a reason for not proceeding with the cause, because it’s something sensitive. I think it has to be addressed head on and we have continued to do that,” he said, noting that many Jews have converted to Catholicism because of reading Chesterton, “and they don’t see any whiff of hostility toward the Jews in Chesterton’s writings.”

Going forward, Ahlquist said that the decision not to advance Chesterton’s cause in Northampton is “not the end of the line,” but he plans to approach several other bishops who he believes might be open to pursuing the cause, though he declined to give names.

“There are many bishops around the world who have a devotion to Chesterton, and I think they would be very cooperative and very willing to entertain our petition to open the cause,” he said.