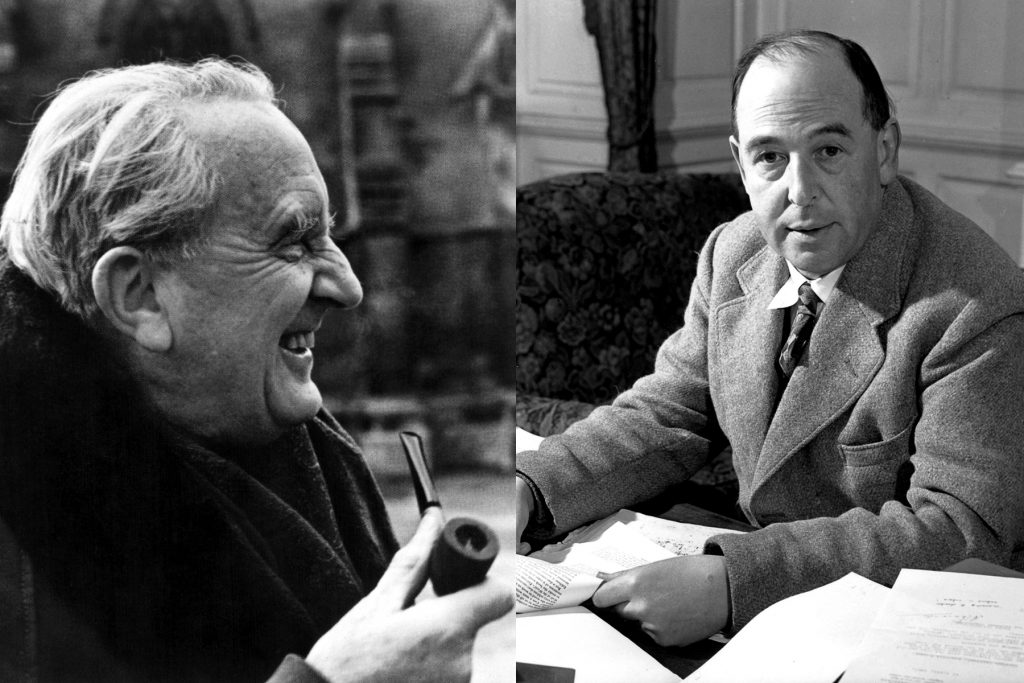

In his autobiography, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life, C.S. Lewis said his friendship with J.R.R. Tolkien “marked the breakdown of two old prejudices. At my first coming into the world I had been (implicitly) warned never to trust a Papist, and at my first coming into the English Faculty (explicitly) never to trust a philologist. Tolkien was both.”

Colin Duriez, writing in his book Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship, explains that their literary friendship was not incidental: “Without the persistent encouragement of his friend, Tolkien acknowledged, he would never have completed The Lord of the Rings.” In turn, Lewis’s journey toward Christianity was guided, and perhaps largely inspired, by Tolkien’s own Catholic faith.

They’d met at Oxford on May 11, 1926, having both joined the faculty the year before. Their first meeting was a bit contentious, according to Duriez. Tolkien admitted that he didn’t care for Edmund Spenser, a favorite of Lewis. Tolkien thought the study of language—his discipline—to be superior to the study of literature. Literature, Tolkien joked, “is written for the amusement of men between thirty and forty.” That night, writing in his diary, Lewis concluded of Tolkien: “No harm in him: only needs a smack or two.”

Their friendship would soon blossom. They met on Monday mornings for drinks. Lewis wrote in his letters: “This is one of the pleasantest spots in the week. Sometimes we talk English school politics: sometimes we criticize one another’s poems: other days we drift into theology or the state of the nation; rarely we fly no higher than bawdy and puns.” Their friendship expanded into a group of writers, known as the Inklings, who would share their work. Lewis wondered: ““Is any pleasure on earth as great as a circle of Christian friends by a good fire?” During their meetings, he read from The Screwtape Letters, and Tolkien read from The Lord of the Rings, among other works-in-progress. Colin Duriez notes that “Tolkien found in Lewis an appreciative listener for his burgeoning stories and poems of Middle-earth . . . Lewis equally had to appreciate Tolkien, whose views on myth, story, and imagination helped him eventually to believe in God’s existence.” For Tolkien and Lewis, Christian belief was generative rather than restrictive.

Lewis’s journey toward God, though, was not simple. He was initially a curious unbeliever, who had read G.K. Chesterton’s Everlasting Man and “for the first time saw the whole Christian outline of history set out in a form that seemed to me to make sense.” Soon after that, a month before first meeting Tolkien, the “hardest boiled of all the atheists I ever knew” sat across the room from him at Oxford and “remarked that the evidence for the historicity of the Gospels was really surprisingly good.” Lewis concluded: “If he, the cynic of cynics, the toughest of the toughs, were not—as I would still have put it—“safe,” where could I turn? Was there then no escape?”

Escape soon became journey. In the years following the start of his friendship with Tolkien, Lewis would be sitting “alone in that room in Magdalen (Oxford), night after night, feeling, whenever my mind lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.”

Tolkien’s influence and inspiration for Lewis, we might imagine, came from the former’s breadth of experience and intellect, coupled with his religious devotion. Tolkien, a devout Catholic his entire life, especially felt the emotional and nostalgic pull of Latin. “If you have these by heart,” he said of Latin prayers, “you never need for words of joy.” Despite his criticisms of the liturgical changes during the Second Vatican Council, Tolkien told his son “there is nothing to do but to pray, for the Church, the Vicar of Christ, and for ourselves; and meanwhile to exercise the virtue of loyalty, which indeed only becomes a virtue when one is under pressure to desert it.” When Lewis said Tolkien was one of the “immediate human causes of my conversion,” we should not doubt it. Faith, it seems, is infectious.

Nick Ripatrazone has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is a Contributing Editor for The Millions. He is writing a book on Catholic culture and literature in America for Fortress Press.

Start your day with Always Forward, our award-winning e-newsletter. Get this smart, handpicked selection of the day’s top news, analysis and opinion, delivered to your inbox. Sign up absolutely free today!