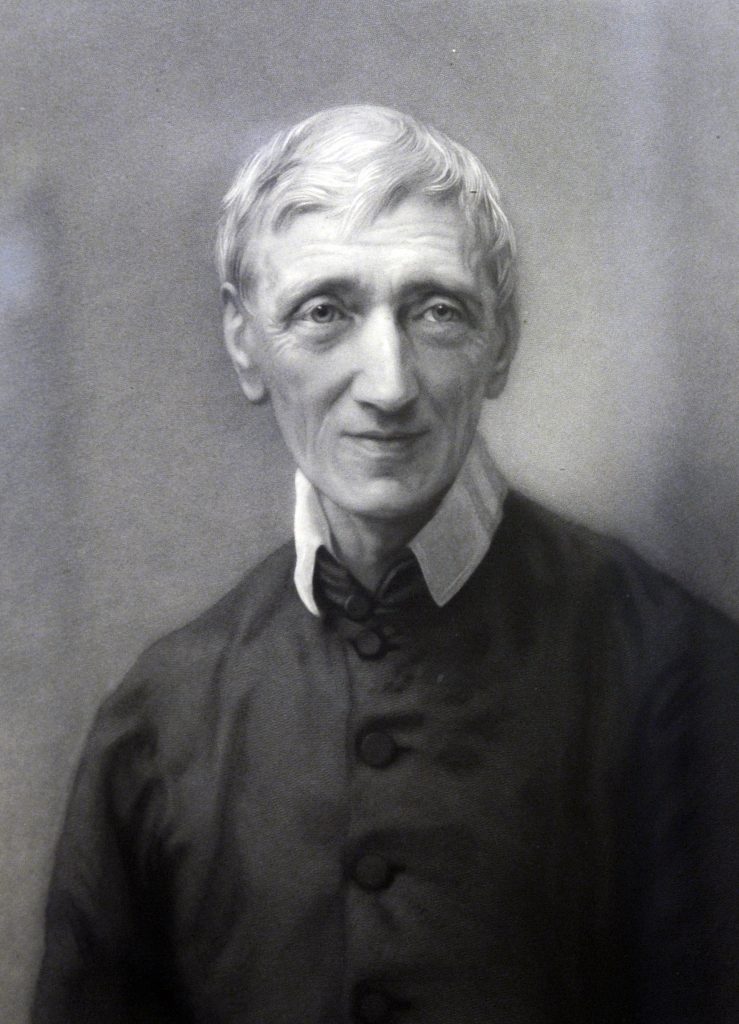

ROME — Theologically speaking, all saints are equal. In terms of star power, however, some are more equal than others — and on Feb. 13, the Vatican announced that two of the most celebrated, and also controversial, Catholic figures of the 19th and 20th centuries have moved a step closer to a halo.

A decree from the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints approved by Pope Francis recognized a miracle attributed to the intercession of Blessed John Henry Newman, which clears the way for the canonization of the19th-century theologian, essayist, and convert from Anglicanism.

Newman was arguably the most influential Catholic writer in the English language of his day.

In the same decree, “heroic virtue” was attributed to Cardinal József Mindszenty of Hungary, who died in 1975 after spending eight years in a Communist prison and then 15 long years living as a refugee in the American embassy in Budapest.

Mindszenty became a global icon of Catholic resistance to communism, and embodied the suffering of the “Church of silence” behind the Iron Curtain.

A finding that a person exhibited heroic virtue is the first of three hurdles that must be cleared before sainthood, and it entitles Mindszenty to be referred to as “venerable.” The wait is now on for one miracle for beatification and another for canonization, the formal act of declaring someone a saint.

In terms of the Catholic understanding of sainthood, canonization is a recognition that someone is already in the afterlife enjoying the beatific vision of God. In other words, it does nothing for the saint — instead it’s for the rest of us, lifting a particular person up as a role model of holiness and a new friend in heaven.

So, what do the examples of Newman and Mindszenty have to teach?

In Newman’s case, one compelling aspect of his life is how he incarnated what Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI refers to as the symbiosis between reason and faith — that reason without faith ends in skepticism and nihilism, while faith without reason becomes fundamentalism and extremism.

Newman’s theological output was prolific, including works such as “Apologia Pro Vita Sua” (1864) and “Grammar of Assent” (1870). Among other things, he’s known for his concept of the development of doctrine, meaning that the Church’s understanding of a given doctrine can gradually develop over time.

Cardinal József Mindszenty in 1962. (WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

With Mindszenty, the lesson may well be fidelity. He was absolutely unyielding on matters of principle, inspiring countless believers and dissidents in the Soviet sphere.

During his trial and imprisonment, Mindszenty was subjected to torture and humiliation, drugged and forced to listen to obscenities, all calculated to elicit a confession. Eventually Mindszenty signed a statement of his crimes, but he had the presence of mind to add the Latin initials “c.f.” for “coactus feci,” or “I was forced.”

Breaking Mindszenty turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory for the Hungarian authorities, as his story had a huge impact on public opinion around the world and revealed the repressive nature of the Communist state.

However, there’s another lesson to be gleaned from both Newman and Mindszenty, one which is less about spirituality than ecclesiastical politics. In a nutshell, it’s this: How someone is seen by Church authorities in his or her lifetime isn’t necessarily the last word about how history will judge them.

In Newman’s case, he was kept at arm’s length during the papacy of Pope Pius IX, in part because of his reservations about the dogma of papal infallibility proclaimed at the First Vatican Council (1869-1870) — not over the content of the dogma but the fashion in which it was declared.

He later advocated minimizing the scope of the dogma, restricting its application to just a handful of papal pronouncements.

Legendarily, Cardinal Henry Manning, a strong proponent of the infallibility dogma, saw Newman as suspect.

The two men also differed over the role of the laity, with Manning upholding a staunchly clericalist view of Church life while Newman anticipated the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) by promoting independent lay action. Manning actually tried to block Newman’s candidacy as a cardinal under Leo XIII, unsuccessfully.

With Mindszenty, he was allowed to leave Hungary in 1971 as part of a deal negotiated by aides to St. Pope Paul VI with the Communist authorities, in which a 1949 excommunication of everyone involved in his trial imposed by Pope Pius XII was lifted.

Paul VI wanted Mindszenty to resign as the Hungarian primate so that new leadership could be imposed but he refused, and there was no Church law at the time requiring bishops to submit resignations at a certain age. Eventually Paul VI stripped Mindszenty of his title in 1973, though he declined to name a replacement until after Mindszenty died in 1975.

Both men, in other words, were at times seen with suspicion by others in power. With the benefit of time, however, they’re now viewed as exemplars of a holy life and heroes of the Church.

Among other things, that lesson probably ought to inspire a bit of caution about hasty judgments concerning today’s renegades, envelope-pushers and dissidents. The mere fact of being in hot water right now doesn’t necessarily mean that history will produce a vindication, of course — but it certainly doesn’t rule it out, either.

John L. Allen Jr. is one of the world’s most respected Vatican analysts. He is founder and editor of Crux. His articles have appeared in the Boston Globe, the New York Times, CNN, NPR, and elsewhere, and he was a senior Vatican analyst for CNN. Allen contributes an exclusive essay to each print edition of Angelus and, through an exclusive content-sharing arrangement with Crux, provides news and analysis to AngelusNews.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!