I’d been looking forward to “Outliers and American Vanguard Art at LACMA” (through March 17) for weeks.

And let me say up front that if you’re really interested in outliers, I’d suggest “Raw Creation: Outsider Art and Beyond” (available at the Los Angeles Public Library).

Author John Maizels has a heart for the artists, and an ear and eye for the strangeness of their vocations.

As British art historian Roger Cardinal points out in the Introduction, “Maizels writes with equal zest about drawings, paintings, sculptures, assemblages and performances. … However, what matters is not any material variability of scale but the central fact of the omnipresence of the maker within any true artwork. …

“Maizels is quick to show that there is no discovery without context, no context without complexity, and no complexity without the need for empathetic understanding.”

Context, understanding, and empathy are in large part what the LACMA exhibit lacks. For starters, there is little to no information, personal or otherwise, about the bulk of the artists. For that, apparently, the guard informed me, you have to take a tour. But if you have to take a tour, and sign up in advance, why not put that up on the website rather than spring it on the visitor who, like me, likely has a two-hour window?

As it was, I blundered through, overwhelmed by the size and underwhelmed by the fact that the exhibit’s focus on the way outsider art has come to be appropriated and marketed by the avant-garde consistently overshadows the oddness, mysterious apartness and genius of the artists themselves.

The first galleries focus on the period between World Wars I and II — “focus” meaning the approach of critics, art institutions, and commercial galleries to outliers, rather than on the artists themselves.

I warmed to Florine Stettheimer’s “naive” oil painting “Father Hoff,” but I had to research later to discover that she was a wealthy socialite, known for her innovative use of cellophane in set designs, and, along with her sister Carrie, created the Stettheimer Dollhouse, which is now housed in the Museum of the City of New York.

“Subsequent galleries examine the effects of the civil rights, feminist, gay liberation and countercultural of the postwar era, especially during what might be termed the ‘long’ ’70s.”

But don’t outsider artists, by definition, operate pretty much independently of social, political, and cultural movements? Isn’t that precisely their glory?

I am second to none, for example, in my admiration of Sam Doyle (1906-1985). But I somehow doubt that, in his dilapidated shack on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, painting Gullah voodoo doctors, fishermen, barbers, and midwives with house paint on scraps of discarded sheet metal, Doyle was terribly influenced one way or the other by, say, “gay liberation.”

Moreover, in trying to shoehorn outliers into the commercial mainstream, and vice versa, the exhibit inexplicably classes as “outliers” such well-known artists as Henri Rousseau, Marsden Hartley, and Cindy Sherman, the latter of whose photographs sell for millions of dollars.

We get an obligatory gallery, purporting bravely to defy the “restrictive values underpinning conventional roles assigned to women,” which features grotesque mutilations, caricatures, and violence against women. OK, then!

Most to the point, the exhibit skirts what really makes outliers outliers: namely, that they’re often somewhat if not fully crazy.

Take Forrest Bess (1911-1977). Bess lived in an isolated fishing camp on the Gulf Coast of Texas and is remembered mainly for cutting off his own penis. The section was accompanied by 10 not terribly compelling paintings, and I couldn’t shake the sorrowful sense that, like all of us, maybe Forrest just needed a friend.

In fact, what struck me way more than any purported effect of political and social upheaval on these “eccentric visionaries” was how many of them were obsessed with God, the Bible, Mary, and Christ.

Recluse Henry Darger (1892-1973), for example, worked as a janitor in a Chicago women’s hospital. He also spent decades painting his simultaneously enchanting and disturbing murals of the sexually ambiguous Vivian Girls, pinafore-wearing soldiers who fight to end child slavery and oppression.

“Shadowing the girls’ travails are references to martyrdom, an inescapable part of the author’s Catholic faith, along with memories of his traumatic youth.” Now we’re talking!

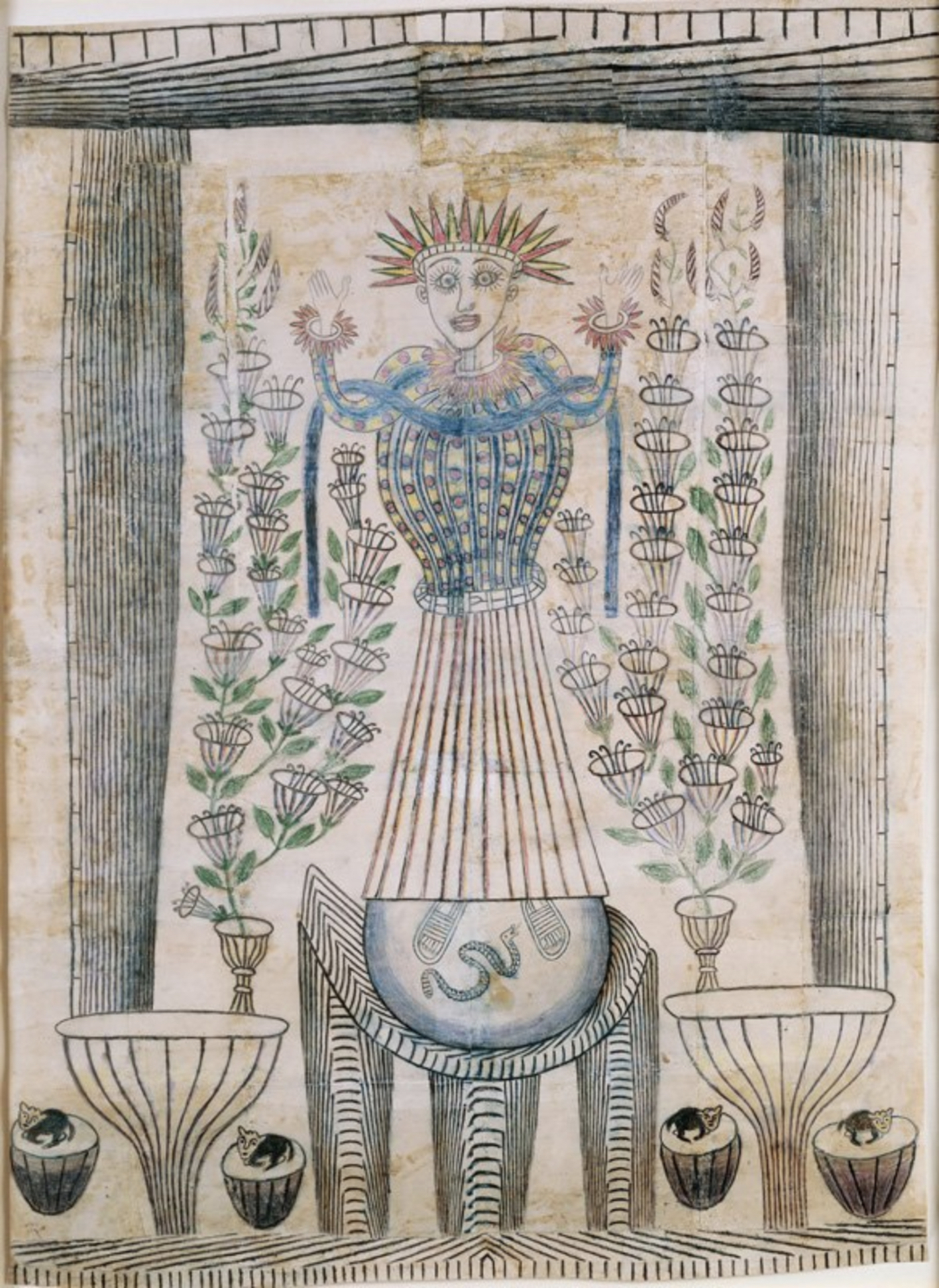

Martin Ramirez (1895-1963), a former peasant rancher, was institutionalized for years at the DeWitt State Hospital near Sacramento. His hallucinatory drawings include a splendidly detailed Madonna with a big crown and teeny hands, done entirely in pencil and blue crayon.

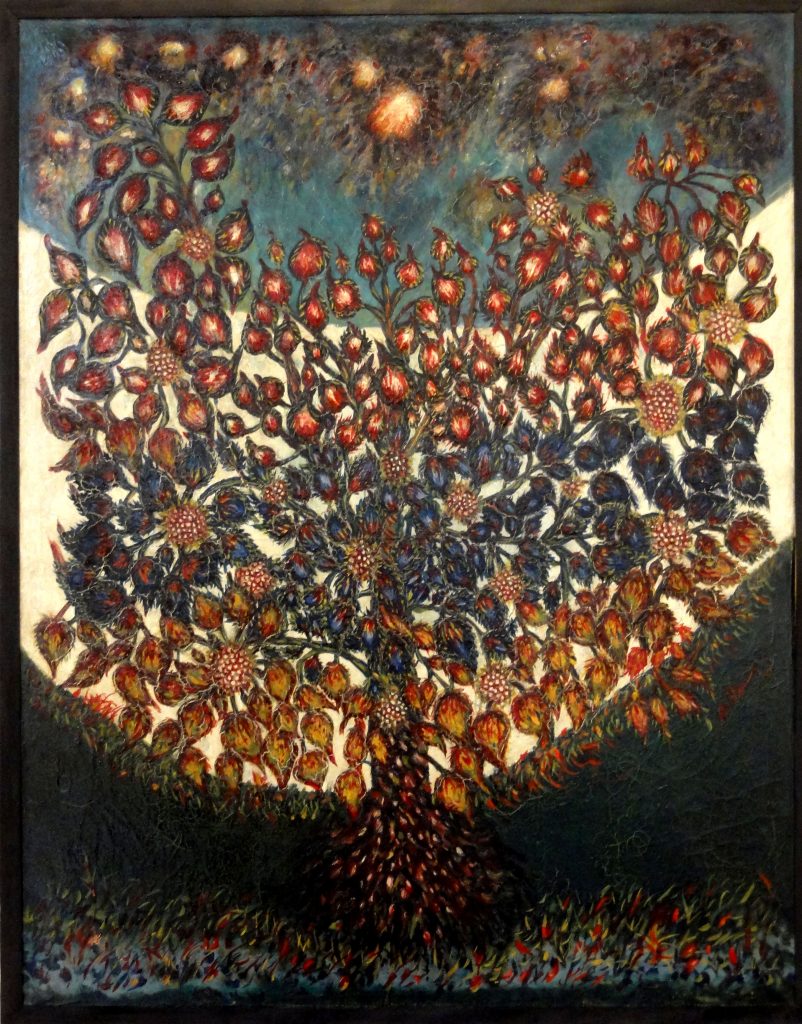

Séraphine Louis (1864-1942) worked as a cleaning lady in a Catholic convent, painted “ecstatic visions of fruit, flowers, and foliage,” made her own pigments from altar candle wax and possibly blood, and died in a mental institution.

The exhibit is worth visiting if for no other reason than her two sublime oils, both of which manage simultaneously to explode with exuberance and a hint of darkness.

“Healthy people don’t need a doctor; sick people do.” The intersection of artistic creativity and mental and emotional suffering: now that would make an interesting exhibit.

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books. For more, visit heather-king.com.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!