Though the week between Christmas and New Year’s is traditionally a fairly slow period on the Vatican beat, this is the Pope Francis era, when tradition and a Euro will buy you a cup of cappuccino in a Roman café.

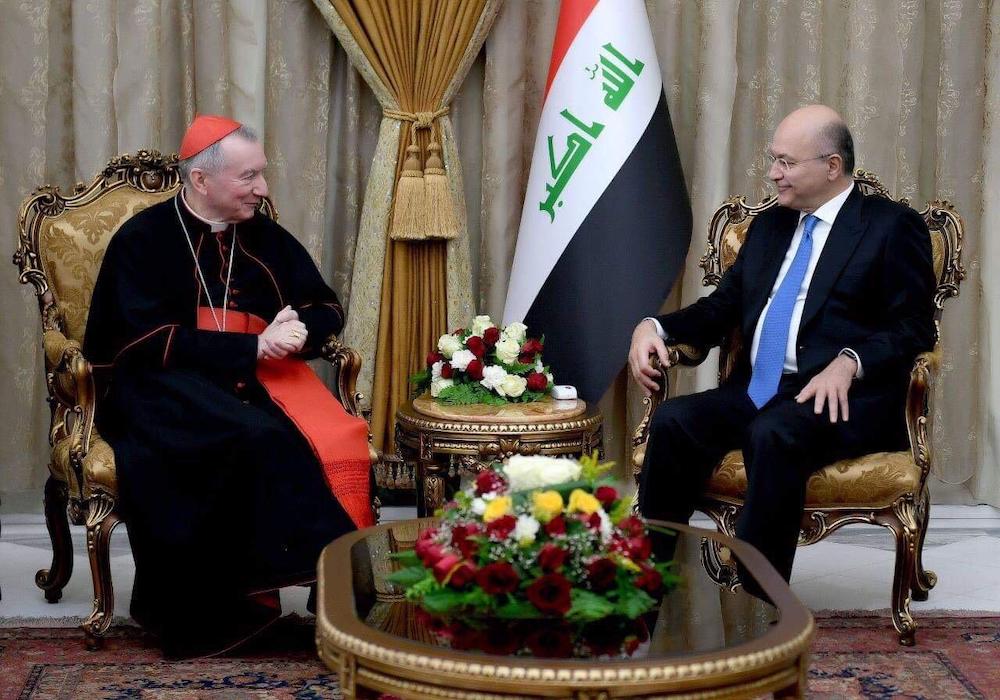

Thus it’s entirely fitting that arguably one of the Vatican’s most important diplomatic encounters of 2018 came the day after Christmas, when Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Secretary of State, met Iraqi President Barham Salih in Baghdad.

During the meeting, Salih extended an invitation to Pope Francis to visit the Iraqi city of Ur, the Biblical city of Abraham, for an interreligious summit. It’s a trip that St. John Paul II desperately wanted to make in 2000, during a jubilee year pilgrimage to sites associated with salvation history, but the security situation at the time made such a trip impossible.

There was no immediate word from the Vatican whether Francis intends to accept the invitation, although there has been some media buzz about an outing coming as early as February. Doing so would be entirely consistent with his penchant for visiting both the peripheries of the world and also conflict zones.

Parolin was accompanied in the Dec. 26 meeting by the Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church in Iraq, the largest of the Eastern churches in communion with Rome in the country, Cardinal Louis Raphael Sako. That was an important signal, in part underlining that the Vatican isn’t interested in pursuing a parallel diplomatic track with Baghdad that doesn’t prioritize the concerns of the local church.

(That’s a real concern, given the fact that critics insist the Vatican has done precisely the opposite in some other parts of the world, including China and Russia.)

According to a statement afterwards from the Iraqi president’s office, Salih and Parolin discussed the importance of different religions working together to combat extremist ideology “that does not reflect the beliefs and values of our divine messages and social norms.”

The statement also said the two leaders discussed the situation facing Christians in Iraq, talking “a great deal” about how to maintain their presence in the country and to assist in rebuilding their homes, businesses and places of worship in the wake of devastation caused by ISIS and other extremist Islamic forces.

As is well known, the Christian presence in Iraq has been declining since the first Gulf War in 1991. From a high estimated at 1.5 million people, today the best guess for the size of the Christian population in Iraq is around 350,000, and many observers say that number would be even lower if visas to travel to the West were easier to obtain.

Father Gabriel K. Tooma, pastor of a church in another of the region’s Christian villages, in June offered Crux the gloomy forecast that “if somebody flung open the doors tomorrow, everyone would leave.”

The meeting between Parolin and Salih, and the possible follow-up that might result, is a potential turning point for at least three reasons.

First, it could have an impact on Iraq’s internal politics. Salih, who took office in October, is a secular Kurd. When he was elected, many members of the country’s hardline Muslim factions objected on the grounds that he wouldn’t be tough enough about enforcing the country’s Islamic identity. He’s pursued a largely tolerant line towards religious minorities, symbolized by the fact that the Iraqi government recently declared Christmas a public holiday.

Salih attended Christmas Mass at St. Joseph’s Cathedral in Baghdad, and afterwards tweeted out: “Christians [have been] assaulted by extremists not only in Iraq but throughout Middle East, in Syria, Egypt, etc. They persevered with dignity and courage and maintained [their] commitment to this land, [to] peace.”

“We are united in our humanity, rejecting discrimination,” the Iraqi leader said.

If Salih is able to arrange a successful papal visit to the country, it could boost his stock, and, by extension, the prospects for moderate secular rule in one of the Middle East’s cornerstone societies. Of course, things could break in precisely the opposite direction, with rolling out the red carpet for a pope enraging the extremists and deepening tensions. Either way, however, the point is that the visit would be consequential.

Second, there’s geopolitical significance to Vatican/Iraqi relations.

Virtually every serious expert on international affairs agrees that, whatever else it may be, religious freedom and tolerance are vital global security issues. Extremism leads to conflict; tolerance fosters peace, development and prosperity across the board.

Without using that vocabulary, every recent pope has aspired to a role we might call “chairman of the board” for religious moderates around the world. Popes have the biggest bully pulpit on the global stage, and they also have a unique power to convene - it’s a rare soul, to put the point differently, who would turn down an invitation for some face time with a pontiff.

If the Vatican and Francis decide to invest a greater share of that political and social capital in the Middle East in 2019, depending on how artfully they do it, the result could be a leavening effect all across the region - emboldening and boosting the stock of moderate leaders, while marginalizing extremist voices.

Third, the Rome/Baghdad summit is also critically important for the future of the local Christian community.

Although of late financial and logistical assistance to Iraqi Christians has begun to flow into the country at the initiative of the Trump administration, Archbishop Bashar Warda of Erbi told Crux the needs remain “immense” and help from the rest of the international community is desperately needed.

Moreover, it’s not just the neglect of foreign actors that has sometimes left Iraqi Christians feeling abandoned. They also routinely complain that they don’t get much support from Baghdad either, both in terms of money and security, in part because the central government lacks effective control over some regions of the country, and in part because it simply lacks the resources.

Tighter relations between the Vatican and the Iraqi government might change that calculus, giving Rome the chance to exercise a bit of diplomatic pressure on behalf of its flock in the country.

At the moment, of course, it’s impossible to know whether any of this will actually happen. However, the prospects for it seem greater after Dec. 26 than before, and for that reason alone, Iraqi Christians will probably remember the 2018 edition of St. Stephen’s Day - by coincidence, the first martyr in the history of the Church - as a pretty good day.