“The Doctor,” an early short story by Andre Dubus, begins as winter passes into spring. Melting snow runs down slopes, onto roads, and resurrects brooks. Art Castagnetto wakes to crisp Saturday morning sunlight, and goes on a run. This is 1969, the cusp of the American running boom. Art doesn’t take to the track—he runs “on the shoulder of the road, which for the first half mile was bordered by woods, so that he breathed the scent of pines and, he believed, the sunlight in the air.” He is wearing a t-shirt and shorts; his sweat suit was ditched into the laundry basket, unneeded until the fall.

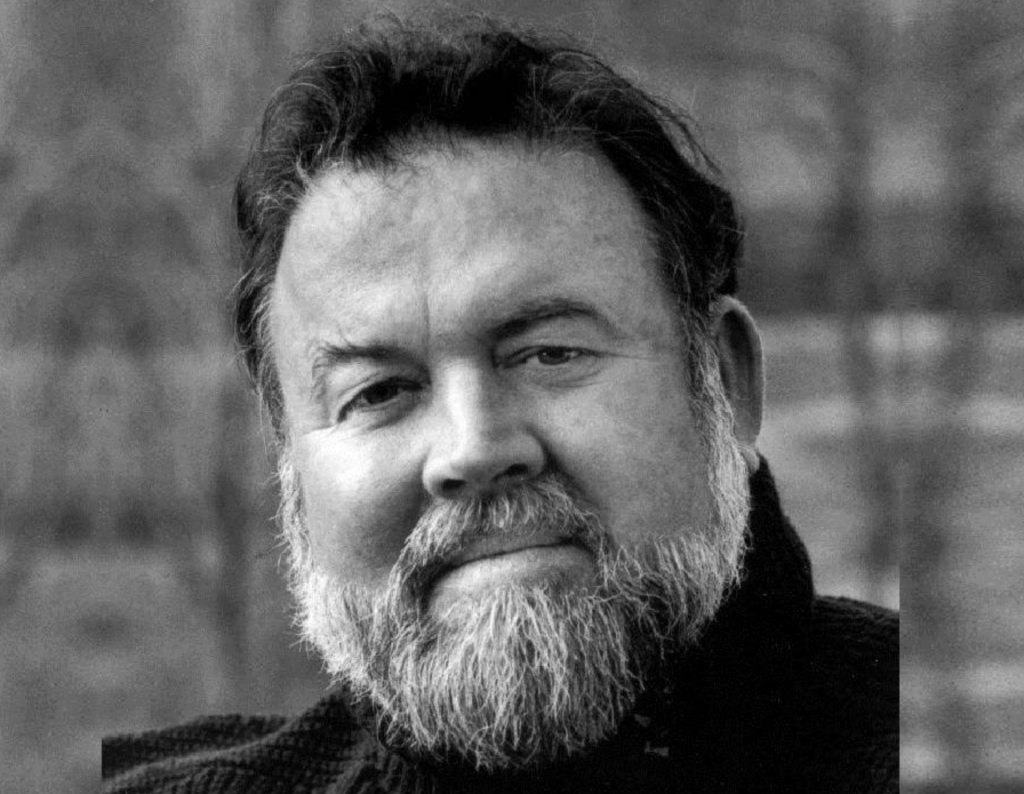

Andre Dubus was a writer of seasons and cycles: both atmospheric and liturgical. Born in 1936, he was trained by the Christian Brothers down in Lafayette, Louisiana, and would carry those cycles to Massachusetts, where he lived and taught for many years. His characters are usually Catholic. Often believers, they are defined by their ethnic, cultural Catholicism. Some are good people; all of them struggle and sin. They are often working people: down on their luck, and getting worse.

David R. Godine, Dubus’s longtime publisher, has recently released three anthologies of his fiction. They are nicely presented and arranged, and span his entire career, except for stories in Dancing After Hours, his final and weakest collection (that book was most notable for republishing “The Intruder,” his first story, which appeared in The Sewanee Review while Dubus was still in the Marine Corps). Godine is bringing back Dubus’s best work.

Dubus is well-known in writing programs. His stories are quite teachable: there is nothing inscrutable here. He was publishing at the same time as William H. Gass, John Barth, and Donald Barthelme, but disdained their literary pyrotechnics. You can see the flesh and skeleton of his stories, but they are never simple. And he only wrote one novel—The Lieutenant, his first book—so his work can be read, discussed, and appreciated in a single sitting. His stories are methodical, but never empty. Plot, precise language, ambiguity, complex characterization: it’s all there.

Short story writers already know and respect Dubus. Why, then, do we need a re-issue of his stories in 2018? One reason is practical. His Selected Stories, published in 1995, included classic stories like “The Pretty Girl” and “A Father’s Story,” but missed “The Doctor,” “Bless Me, Father,” “Separate Flights,” and other short but unique stories that help round out Dubus’s canon. These new volumes offer the most comprehensive look yet at his fiction. They also offer the opportunity for fine introductions from Ann Beattie, Richard Russo, and Tobias Wolff—long essays that consider Dubus with care.

“The Doctor” appears in the first volume, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, which collects his first two books, Separate Flights and Adultery & Other Choices. Beattie’s introduction focuses on the importance of loneliness in Dubus’s fiction, and she’s right to consider this theme. “The Doctor” feels claustrophobic because we remain inside Art’s exasperated mind through Dubus’s patient third-person narration. She praises his female characters as “well conceived.” He remains “close” to them, and “lets us watch fairly conventional power struggles between men and women work out unexpectedly, because there is always the inclusion of fate.” Beattie also adds what amounts to a warning: “What Dubus observes, he clearly does not endorse.”

Dubus showed people at their worst, sometimes with only the faintest light of hope moving them forward. A spiritual emptiness plagues many of his characters. His story “In My Life” ends with the main character looking over her boyfriend’s shoulder in the bedroom, and “there was pale light at the window.” Readers of short fiction from the 70s and 80s might recognize that type of line. In 1983, Granta magazine editor Bill Buford coined the term “dirty realism” to describe a new fiction “emerging from America, and it is a fiction of a peculiar and haunting kind.” Buford claims this new fiction is distinctly American, but not in the traditional senses. It is not heroic or grand. It is neither experimental, nor historical. Instead, this fiction is “devoted to the local details, the nuances, the little disturbances in language and gesture.” These were “unadorned, unfurnished, low-rent tragedies about people who watch day-time television, read cheap romances or listen to country and western music.” Stories about waitresses, cashiers, construction workers. Stories about people in trouble. And perhaps most importantly, writers who had mastered the short story form.

Buford devoted an entire issue to these writers: Jayne Anne Phillips, Richard Ford, Raymond Carver, Elizabeth Tallent, Frederick Barthelme, Bobbie Ann Mason, and Tobias Wolff. He says that he wished he had more room to include Mary Robison and Ann Beattie. An impressive lineup of writers, with one glaring omission: Andre Dubus. Dubus’s fiction contained all of the elements that Buford praised in his contemporaries: simple yet precise language, troubled but endearing characters, and a disdain for linguistic pyrotechnics that made writers like John Barth and Thomas Pynchon seem “pretentious in comparison.” He’d already published several story collections. So why not include Dubus?

Buford must have had his reasons for leaving Dubus off the roster—but I do think Dubus’s work existed in a different realm from his contemporaries. He wrote about the same type of character, in the same type of situation, using the same type of language as them—but as an earnest, and often sentimental, Catholic, Dubus placed his characters within a context of theology, sin, and salvation. Although Wolff and Barthelme were both Catholics, their past or present faith was more in the background. In contrast, Dubus’s stories often hinge on theological points His stories were devotional but never doctrinaire; more so than any other Catholic short story writer in the shadow of Vatican II, Dubus captured a rift that Gaudium et Spes lamented: “the dichotomy between the faith which many profess and the practice of their daily lives.” For Dubus, that was just life.

Dubus tried to answer the same questions as fellow Louisiana Catholic Walker Percy in his fiction, but with different results, and a vastly different method. It is tempting to synthesize Dubus, Percy, and Flannery O’Connor in some grand unified theory of Southern Catholic literature, but Dubus breaks the formula. Like O’Connor, he was a cradle Catholic, and he did write about violence—but his characters were often working-class Catholics. Their collars were far bluer than those in Percy’s fictions. Although he could be self-deprecating in essays and interviews, Dubus was often deadly serious in his fiction. Although we might see theological and moral questions pondered in his fiction, they are done at the dinner table or in the bedroom, not within abstractions. His characters are real, his plots are real, and even his syntax is real—there is no artifice in his fiction.

Dubus’s Catholicism is earnest. It is emotional, not intellectual. His characters do bad things, and they often feel guilty about them. O’Connor’s fiction exists in a world of strangeness: river baptisms, bombastic preachers, and comic violence. Her Catholicism, then, is an acceptable Other. Dubus’s Catholicism is domestic, and somehow more perplexing.

When I think of Dubus, I often return to the end of his story “Anna.” Wayne is cooking hamburgers at Wendy’s. Anna listens to the end of a Waylon Jennings record before going to the laundromat. The air’s moist. She’s among the “gurgling rumble and whining spin of washers, resonant clicks and loud hiss of dryers.” Two women smoke, read magazines, and talk. And then there is Anna, alone. She “took a small wooden chair from the table and sat watching the round window of the machine, watched her clothes and Wayne’s tossing past it, like children waving from a ferris wheel.” It is the perfect Dubus sentence: gracefully hypnotic, curiously innocent, and beautifully sad. You’ve got to believe in something to write that way.

Nick Ripatrazone has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is a Contributing Editor for The Millions. He is writing a book on Catholic culture and literature in America for Fortress Press.