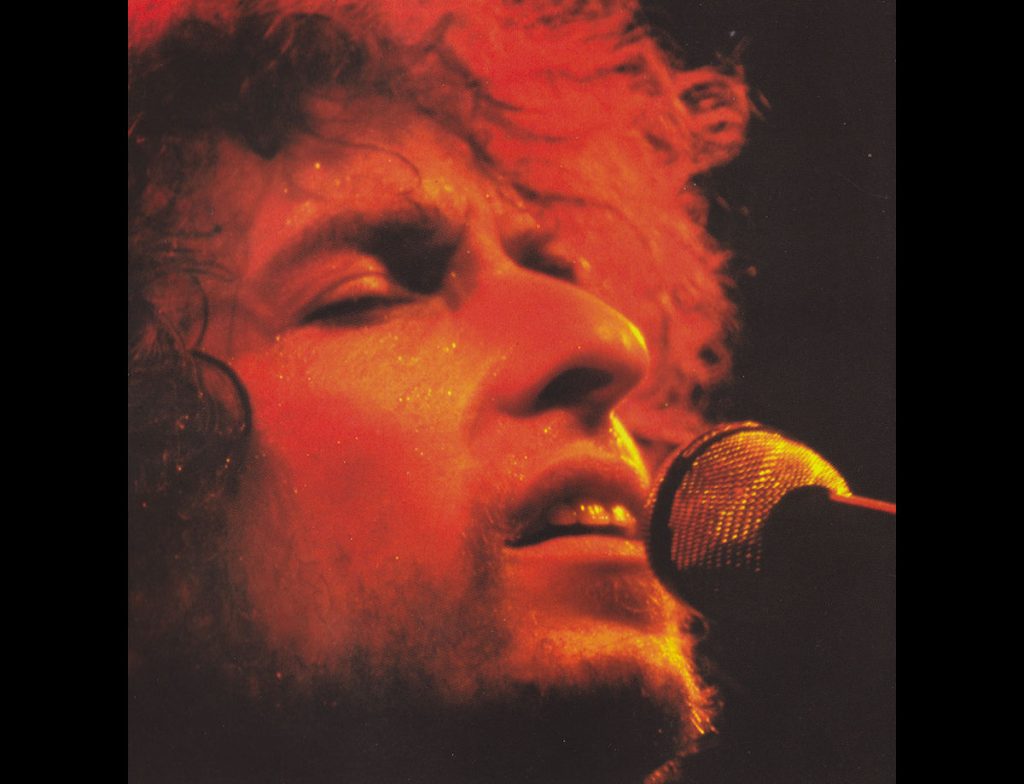

A new collection shines a light on when Bob Dylan found Jesus — and why it still matters.

To understand the cultural moment that is preserved in the new boxed set of collected live performances and outtakes from Bob Dylan’s gospel years, “Trouble No More: The Bootleg Series, Volume 13, 1979-1981,” it is helpful to recall a comment by the folksinger Phil Ochs, who was close to Dylan early in his career.

Ochs said in 1970, “If there’s any hope for America, it lies in a revolution, and if there’s any hope for a revolution in America, it lies in getting Elvis Presley to become Che Guevara.” That was his way of telling his audience of Baby Boomers — the hipster elite known as Woodstock Nation — that they could not succeed in molding the culture to their image unless they first won over the hearts of Middle America.

The context of Ochs’ observation had to do with the fact that many Baby Boomers, despite being part of the largest generation in America’s history, identified themselves as the “underground”: a cultural elite answerable to no one but themselves. They saw themselves as the cutting edge of a spiritual sword that would cut through the older generation’s hypocrisy and bring in the Age of Aquarius, a time of global peace and harmony.

Presley, although only in his thirties, symbolized to Woodstock Nation an older generation that was spiritually complacent, intellectually backward and culturally impoverished. They could not imagine the former truck driver, whose appropriation of black music styles had helped usher in the age of desegregation, as a champion of the rights of the underprivileged.

But if the idea of Presley becoming Guevara was unthinkable to the self-styled counterculture, even more so was that of Guevara becoming Presley.

G.K. Chesterton, critiquing the intellectual elitism of his day, had an anarchist in his 1908 novel “The Man Who Was Thursday” argue confidently that “an artist disregards all governments, abolishes all conventions.” Bohemian prejudices were much the same in 1978; it was assumed that no revolutionary who had experienced the ecstasies of experimentalism could possibly lower himself to pander to popular notions of the good, the true and the beautiful.

Yet Dylan, in the eyes of many of his counterculture fans, made such a shocking de-evolution — not once, not twice, but three times between his debut album in 1961 and the recordings captured on “Trouble in Mind.”

As Rob Bowman observes in the introduction of his excellent track-by-track annotations for the boxed set, Dylan’s move to gospel in 1978 is of a piece with two earlier artistic moves that upended audience expectations: his debut electric performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 and his album of violin-laden standards, “Self Portrait,” in 1970. On each of those occasions, although some fans greeted the move with enthusiasm, many accused the iconic singer-songwriter of betraying his muse.

The comparison between Dylan’s gospel era and his previous shifts fails, however, on the level of motivation. When Dylan began writing and performing songs like “Gonna Change My Way of Thinking,” he wasn’t merely adopting a new musical style. He was writing in the light of a newfound and, by all accounts, genu ine faith, the fruit of an experience he had in a Tucson, Arizona, hotel room one night in November 1978, when he called upon the Lord and suddenly felt Jesus’ presence.

Following his conversion, Dylan went through a brief but intense discipleship period in which he was tutored by Evangelical ministers from the Tarzana, California-based Vineyard Christian Fellowship. He emerged from it consumed with the desire to share the insights that flooded his consciousness as he discovered the truth and love of Jesus Christ.

Not everyone who heard the Christian Dylan felt the love, least of all critics. San Francisco Chronicle critic Joel Selvin exemplified the feelings of the most virulent naysayers in his 1979 concert review, “Bob Dylan’s God-Awful Gospel.” He castigated Dylan for “no longer asking the hard questions,” and, as if resentful that the artist had forsaken the drug culture, derided him further for partaking of what Karl Marx called “the opiate of the people.”

Other critics who took Dylan to task were concerned more about the direction of his music than the direction of his beliefs. One of the more insightful reviews of his first gospel album, “Slow Train Coming,” came from New West writer Greil Marcus, who faulted the artist not so much for what he said about his faith as for what he omitted about it.

“What [Dylan] does not understand,” Marcus wrote in a review titled “Amazing Chutzpah,” “is that by accepting Christ, one does not achieve grace, but instead accepts a terrible, lifelong struggle to be worthy of grace, a struggle to live in a way that contradicts one’s natural impulses, one’s innately depraved soul.”

From Marcus’ standpoint, the songs on “Slow Train Coming” lacked any tension between life in this world and in the next. That tension, the critic argued, was key to the effectiveness of great gospel music such as Presley’s recording of the classic “Peace in the Valley.”

Many of the songs on “Trouble No More” that date from the first year of Dylan’s conversion (when “Slow Train Coming” was recorded) bear out Marcus’ criticism. In tracks like “Gonna Change My Way of Thinking” and “When You Gonna Wake Up?” (which appear on “Trouble No More” as live performances), the artist presents the Christian way in language reminiscent of the “two paths” tradition of biblical wisdom literature. It is a binary approach that focuses upon the objective aspect of salvation, in which one is either saved or not, rather than the subjective aspect, in which one undergoes the ongoing purgation that comprises co-crucifixion with Christ (as in Galatian 2:19-20).

In other words — and this is, I believe, what Marcus was getting at — Dylan as a new convert had a concept of salvation that was severely lopsided in the direction of the “once saved, always saved” Evangelical mentality he had absorbed through his Vineyard mentors. Some of his lyrics from that period present an image of faith that is almost semi-Pelagian, interpreting failure to live up to the Gospel as though it were a weakness of will. In “Gonna Change My Way of Thinking,” he sings of Jesus, “He said, ‘He who is not for Me is against Me’ / Just so you know where He’s coming from.”

Likewise, Dylan’s lone reference to “spiritual warfare” carries a tone of macho triumphalism that St. Paul, who originated the expression, was careful to avoid. “Now there’s spiritual warfare and flesh and blood breaking down,” he sings in “Precious Angel.” “Ya either got faith or ya got unbelief and there ain’t no neutral ground.” True enough, but where is the sense of God’s grace present even in the breakdown of flesh and blood, as Paul describes so beautifully when speaking of his weakness and sufferings (2 Cor 12:7-10, Col 1:24)?

Yet, even in the recordings from his first flush of faith, Dylan offers hints that, as Leonard Cohen would say, the cracks in our spiritual armor can ultimately serve as points of entrance for the light of Christ. In the various renditions of the “Slow Train Coming” track “When He Returns” that appear on “Trouble No More,” (particularly the live version on the accompanying video documentary) he puts forth a sense of sacred vulnerability, creating an intimate space as only a great artist can. He sings of Jesus, “It is only He who can reduce me to tears,” and the listener cannot doubt for a moment that he means it.

In fact, “Trouble No More,” in giving a detailed overview of Dylan’s entire gospel period, shows that Dylan, consciously or not, ultimately not only addressed the flaws that Marcus observed but did so in a magisterial manner. Less than a year after conveying a veneer of divinely bestowed indomitability in “Precious Angel,” he could admit in “Covenant Woman,” “I’ve been broken, shattered like an empty cup / I’m just waiting on the Lord to rebuild and fill me up.”

“Covenant Woman” also reveals an additional level of maturity in Dylan’s spiritual outlook: a sophisticated ecclesial sense. Its lyrics suggest he was reading Book 18 of St. Augustine’s “City of God,” with its discussion of the Church as a woman who is a “stranger” and “pilgrim,” and with its account of the Erythraean Sybil, who perceives the Church as knowing the “secrets of every man’s heart God shall reveal in the light.” The song also brings to mind chapters 8 and 9 of the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, “Lumen gentium,” particularly the Council’s quotation from that same section of “City of God” concerning how “the Church, like a stranger in a foreign land, presses forward amid the persecutions of the world and the consolations of God.”

By the time of Dylan’s final gospel album, 1981’s “Shot of Love,” he had no fear whatsoever of admitting to what St. Paul would call the “agon” (“agonizing struggle”) of being caught between the present moment and the Second Coming.

It is a long way from the almost pugilistic attitude of the opening track of “Slow Train Coming,” in which he announces in his best Bobby Zimmerman sneer, “You’re gonna have to serve somebody,” to the heart-wrenching introspection of the final track of “Shot of Love,” “Every Grain of Sand”: “There’s a dyin’ voice within me reaching out somewhere / Toiling in the danger and in the morals of despair … I am hanging in the balance of the reality of man / Like every sparrow falling, like every grain of sand.”

“Trouble No More,” in showcasing versions of those songs and dozens more from Dylan’s gospel period, affords a wealth of insights into what took place between those two moments. It is a moving chronicle of the believer’s journey toward the virtue of true Christian hope, in the sense that Aquinas means when he defines hope as desiring an unimpeded union with God in the manner of “a future good, difficult but possible to obtain.”

And so it was that, for a few years at the cusp of the 1980s, Woodstock Nation’s greatest revolutionary rebelled against rebellion itself, against the old enemy whom Saul Alinsky in “Rules for Radicals” admired as “the very first radical.” Although he afterward returned to secular music, he never disavowed it. In fact, in 2015, when receiving the MusiCares Person of the Year Award, he even indicated a desire to record another gospel album.

What was rebellious four decades ago remains rebellious now. Many hipster music fans today would likely shudder if one of their icons announced as Dylan did that he was henceforth dedicating his life and artistry to the spread of the kingdom of Christ. The music of “Trouble No More,” and the story it tells, stands as a reminder that, although “the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, … to us who are being saved it is the power of God” (1 Corinthian 1:18).

Dr. Dawn Eden Goldstein is an assistant professor of dogmatic theology at Holy Apostles College and Seminary and, as Dawn Eden, is the author of several books.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.