Why did we need the Second Vatican Council? Did we need it at all? Hearing those questions, most Catholics who’ve thought about Vatican II would probably cite renewing and updating of the Church as solid reasons for the ecumenical council.

That answer isn’t wrong. But a half-century after Vatican II (it took place between 1962 and 1965) it’s clear that a much larger purpose was at work, with Church renewal and updating its handmaids.

You start to see that when you consider a common objection to the council:

“Other ecumenical councils were convened to handle particular problems. Early councils dealt with heresies about Christ. In the 16th century Trent had to respond to the Reformation. Vatican I in the 19th century faced the challenge to the authority of the pope and the bishops — but it was interrupted and didn’t say much about bishops.

“By contrast, there was no crisis requiring Vatican II. By the middle of the last century, the Church was strong and united in the faith. So this was a council that wasn’t needed. Wouldn’t it have been better to leave things alone?”

No, it wouldn’t. The Church faced a grave problem then — indeed, it still does — and an ecumenical council was required to address it. What problem? No less than the crisis of modernity itself, especially the comprehensive undermining of humankind’s self-understanding and its disastrous consequences for faith, underway in the West for at least a century or more before the council.

This process had many sources, but three especially stand out:

Darwinism — popularized evolutionary theory reducing the human person to no more than a higher animal; Marxism, whose deterministic account of history eliminated free choice; and Freudianism, no less deterministic, which explained human behavior as the acting out of sublimated impulses from libidinous realms of the psyche.

Capping it off was Friedrich Nietzsche, who boldly announced the death of God — the bourgeois deity of 19th century Christianity, that is — and predicted that a new morality of power vested in a superman (ubermensch) would soon emerge. Hitler apparently took that to heart.

Ordinary people were understandably slow in absorbing all this, but it was gospel for the Western cultural elites of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In due course it filtered down to the masses — a process speeded by the horrors of two world wars. Here, then, was the crisis of modernity that Vatican II needed to confront.

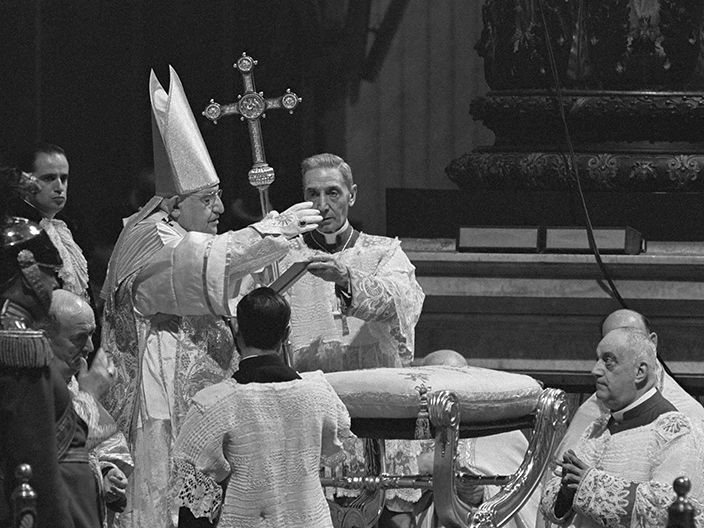

Pope St. John XXIII put it clearly in his opening address to the council on October 11, 1962. The “greatest concern” of Vatican II, he declared, was to guard Christian doctrine and teach it “more efficaciously.” That included the truth about “the whole of man, composed as he is of body and soul” and created by God not only for life on earth but for eternal life in heaven.

The council did its best, and that was pretty good. Central to its teaching was the Christocentric affirmation that it’s Christ who “fully reveals man to himself and makes his supreme calling clear” (Gaudium et Spes, n. 22). The Church has been developing that exalted vision of human dignity ever since, most notably via the personalism of Pope St. John Paul II.

Yes, an enormous amount remains to be done to recapture lost ground. But don’t tell me Vatican II wasn’t needed. It was, urgently. The problem hasn’t been the council but the lack of focus in its implementation— including the constant, distracting bickering about liturgy. And saying Vatican II wasn’t necessary is surely no help.

Russell Shaw is the author of more than 20 books, including volumes on ethics and moral theology, the Catholic laity, clericalism and the abuse of secrecy in the Church. He previously served as communications director for the U.S. Catholic bishops (1967-87) and information director for the Knights of Columbus (1987-97).