The small chamber is hidden, precious, cleaving against the solid wall of the church. You might have walked past without realizing you were steps from a window into the eternal. A shiver between your shoulders reveals you are on holy ground.

What was once a small window on the side of the church is now cemented shut. In front of it, a sign reads: “Site of the cell of Christine Carpenter Anchoress of Shere 1329.” You are standing before the remnant of a medieval anchor-hold.

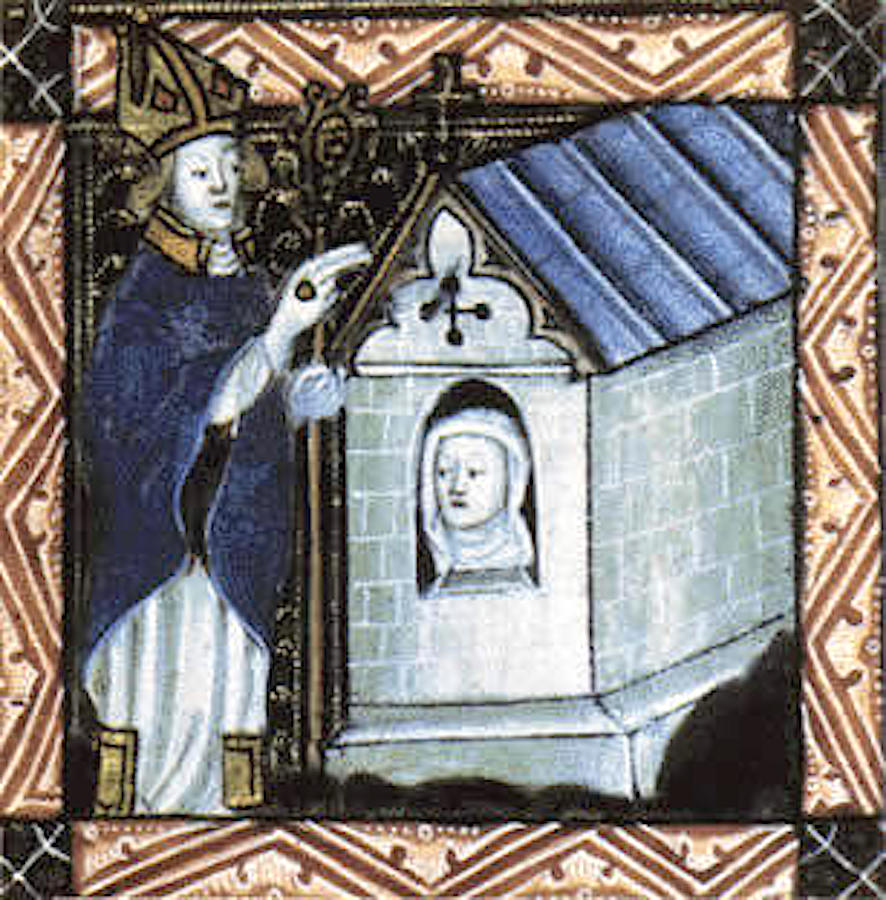

In medieval England, a small select group of upper-class women voluntarily devoted themselves to God by walling themselves in an anchor-hold. There was no entrance or exit, only two windows from which to interact.

The window on the outside of the church, the larger of the two, was for receiving food and water, discarding waste and receiving visitors, parishioners or even pilgrims petitioning prayer and making confession to a priest. Inside, a smaller window called a squint, held the anchoress’ vision, both literally and spiritually; it was from this window that she could see the altar and receive the Eucharist.

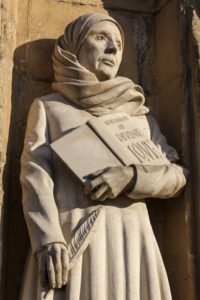

The most renowned of medieval anchoresses was Julian of Norwich. Notoriety was completely contrary to the vocation of an anchoress — her goal was to be hidden, humble, and completely dependent on Christ. Yet it was Julian who was the first woman writer of English. A contemporary of Chaucer, her “Revelations of Divine Love” describes her visions of Christ’s appearance to her when she was gravely ill and has survived the centuries.

Julian’s language is intimate and tender. She uses words like “littleness,” “Loveth,” and yearning,” that may seem antiquated to the modern reader, yet she is giving language to that which is difficult to describe, a mystical experience. She refers to these experiences as “shewings.” She notes a difference between visceral or “bodily sights” and the more ethereal experience of a “ghostly sight.”

This is the language of a person whose entire life had been devoted to Christ.

I had always wanted to see an anchor-hold. Although nearly 800 holds were recorded during medieval times, not many survived King Henry VIII’s destruction of monasteries. Last summer, my friend Colleen took me out to dinner in the Surrey village of Shere, a darling village with buildings from the 15th century (and where the 2006 film “The Holiday” was filmed).

I spied the anchor-hold from the cemetery surrounding the church and cried out, “Is that what I think it is?!” I began running like a child toward the remnants of the hold, now sealed shut. Colleen was a bit chuffed watching my delight. “I thought you’d like that.”

There was a simple sign, verifying my suspicion, “Site of the cell of Christine Carpenter Anchoress of Shere 1329.” I run my hands over the frame of the hold and the cement filling up the window. It was a surprisingly moving moment for me. I shifted from absolute delight to tears on standing at this holy place.

I find it interesting that common scholarship, especially from those outside of the church, regards anchoresses as prisoners, so distraught by the limits of womanhood in a patriarchal society that they were willing to confine or imprison themselves in the walls of a church. They equate it with some sort of madness.

I suppose in a world dedicated to immediate gratification, egoism, and self-interest, one would find it mad to seek only what is eternal. But these women gained freedom in their vocation. It was a refuge from the demands and expectations of society and family to marry and have children. There was massive status associated with becoming an anchoress. You would have been viewed as a saint in the making.

It is curious that only upper-class women were allowed to give their lives in this manner, as one needed a benefactor, usually the anchoress’ well-off family but often a wealthy patron who provided support in exchange for prayers.

Christine Carpenter was not of the upper class. As her surname attests, she was the daughter of a carpenter and had to petition the local bishop to be “enclosed.” Parishioners attested to her character and virginity and the bishop approved her enclosure. It is unknown who provided patronage for her enclosure.

Because Shere was on a pilgrimage route from Winchester to Canterbury, pilgrims would have stopped to seek Christine’s prayers and advice. Christine of Shere, Julian of Norwich, and other anchoresses like them lived in a world much larger than our own. With their eyes fully focused on Christ, in a manner that those of us outside those walls could never attain, they lived beyond time. Seeking what was eternal, they became part of it, seeing what in the Creed is referred to as the unseen.

Few words from anchoresses survive, but Julian gives us a glimpse into this tender space in which they lived. Julian described Christ as “our clothing, that for love wrappeth us and windeth us, halseth us and all becloseth us, hangeth about us for tender love, that he may never leeve us” (139). St. Paul writes in his letter to the Galatians that when we are baptized, we are clothed in Christ. We become a new creation, connected to him.

This sensory metaphor reminds us that Christ should be as close as our own skin. Christ was real to these women. He held them, cared for them, and was as close as their own skin. Christ’s love was available, present, and accessible to these women.

In 1332, three years after her enclosure, Christine left her anchor-hold. There is no documentation as to the reasons she left, but within months, she petitioned the pope to be granted permission to again be walled.

I imagine that the world was too loud, too distracting. I imagine Christine found the loss of intimacy with Christ frightening. This world was too ordinary when his love could be had. I believe not wanting to lose that intimate presence of Jesus is why she returned. Like the Psalmist, Christine prayed: “He is my refuge and my fortress; My God, in Him I will trust.”

There is a word Julian of Norwich used more than others in her “Revelations”: “becloseth.” The word meant to be closed in, to be confined, to shut out what is open, to “becloseth” in Christ.

It was when these women confined themselves in Christ, surrendered themselves to him for every need, that they found they were truly free.