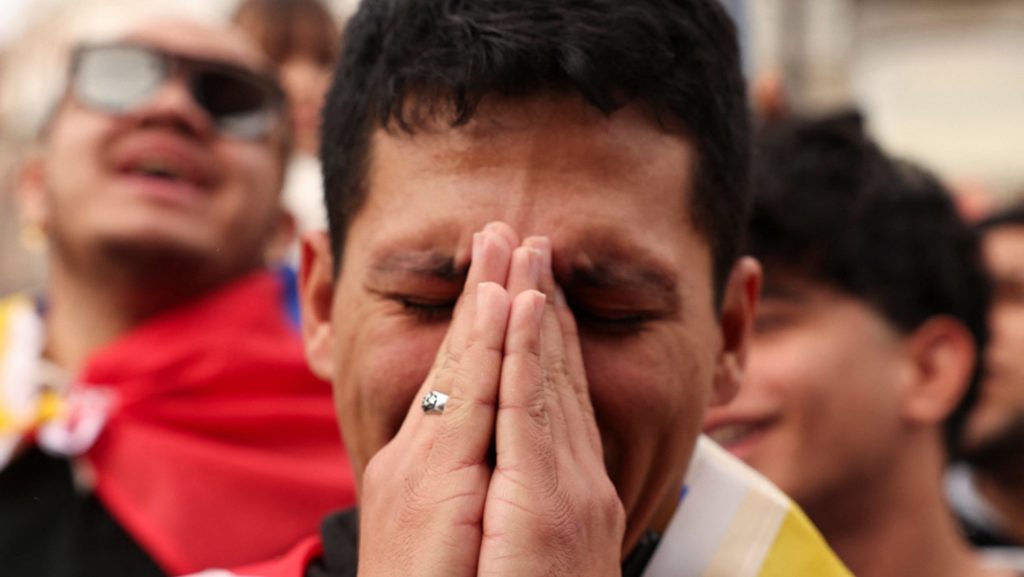

As of Jan. 3, nearly 8 million Venezuelans forced to live outside their country were joined by Nicolás Maduro, the man whose policies and crimes led them to diaspora. The news of his seizure by U.S. military forces and that of his wife, Cilia Flores, to face drug-related charges in New York may be the biggest event in Latin America in decades.

Venezuela has spent the better part of the last decade in an informal state of collapse, with “elections” that settle almost nothing, armed actors and foreign patrons operating in the shadows; and a humanitarian emergency so vast it has reshaped an entire continent.

To some, the cautious response so far from Catholic leadership in Venezuela and Pope Leo XIV may come across as weak. But in reality, it reflects a hard-learned understanding that words are not cost-free in a country where power is enforced not through law, but through fear, surveillance, and unlawful imprisonment.

With that in mind, here are a few thoughts.

The restraint from Leo XIV and the Venezuelan bishops isn’t a bug — it’s the point

The day after Maduro’s capture, Leo in his Sunday Angelus address framed the crisis in moral and juridical terms, calling for the good of the Venezuelan people, the rule of law, human and civil rights, and respect for the country’s sovereignty to be considered.

The statement showed Leo understands that what comes next will determine whether Venezuela moves toward justice or continues its long-running nightmare with a different cast of characters.

The Vatican’s caution is consistent with what Leo told reporters on his return from Turkey and Lebanon a month earlier. He warned of the dangers of a military invasion of Venezuela, urged dialogue with alternative forms of pressure, and noted that the Church’s priority was to calm tensions and keep the focus on ordinary people.

In other words, this is not a pope who is indifferent, nor a Vatican that is absent. It is a Holy See attempting to avoid endorsing any maximalist narrative before the facts — and the consequences — are fully visible.

The same logic applies to Venezuela’s Catholic bishops. Even in less volatile times, they’ve had to walk a tightrope, being critical enough of Maduro to remain credible in the eyes of a suffering population but measured enough to preserve the Church’s ability to operate, especially through humanitarian channels.

The regional comparison is instructive. In Nicaragua, bishops have been jailed, exiled, and stripped of nationality. Venezuela’s repression has been more selective, but no less real. A month before Maduro’s capture, the retired cardinal archbishop of Caracas was blocked from traveling to Spain.

For those who think the Catholic Church needs to be the loudest voice in Venezuela right now, the current tone will disappoint. Her leaders are more focused on parishes staying open, allowing priests to keep preaching, making sure Catholic charity groups can keep feeding a population that has endured extreme hunger, and keeping channels for mediation alive.

Seen from that angle, the Church’s restraint begins to look less like timidity and more like strategy.

“Maduro removed” is not the same as “the crisis solved” — and the next 30 days may be more dangerous than the last 10 years

The fact that Maduro was removed but his power structure was left intact was a disappointment to those expecting a U.S.-sponsored transition to democracy.

But it confirms that Venezuela is still laden with ingredients for institutional failure: competing armed actors, entrenched patronage networks, foreign intelligence ties, and criminal economies that do not politely retire because a head of state has been flown to a courtroom.

That is why any serious Catholic reading of this moment keeps circling back to a prudential question: What protects people on the ground tomorrow morning? Not debates on social media, nor even the hopes of an enormous and influential diaspora, but the realities in Caracas, Maracaibo, Valencia, and the border regions where the line between politics and organized crime has long been perilously thin.

Complicating any transition further are long-standing concerns, raised by U.S. officials and independent analysts, about the operational space enjoyed in Venezuela by networks tied to Iran and Hezbollah, and criminal organizations of Chinese and Russian origins.

The Vatican is proceeding with memory, not naïveté

One reason Leo’s posture appears so calibrated is that the Vatican is not approaching Venezuela as an abstraction. Its diplomatic memory runs deep.

Pope Francis had a complicated, often controversial relationship with the Maduro government. He received Maduro at the Vatican months after his election in 2013, and again in 2016, during a period the Vatican itself described as a “worrying” political, economic, and social crisis for the Venezuelan people. Those encounters reflected Francis’ preference for dialogue, even with leaders widely criticized for human rights abuses.

But Francis still spoke frequently of Venezuela’s suffering, calling for prayer, urging restraint in moments of political escalation, and emphasizing reconciliation and dialogue.

Francis was sometimes criticized as being too indulgent with Maduro’s regime. His allies argued that his overriding concern was to avoid foreign military intervention and further harm to civilians.

Leo’s approach reflects both continuity and change. Shortly before Maduro was seized, Leo warned of the grave risks posed by military intervention and urged that all nonviolent avenues be exhausted. That concern now shapes his public language: sovereignty, the rule of law, and the primacy of the Venezuelan people’s welfare.

There’s no love lost for the Vatican in the fall of Maduro, but the scale of grays has so many grays that it’s hard to tell where black and white are.

The diplomats advising Leo on the situation have extensive experience with Venezuela. Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin was the papal nuncio there during some of its most turbulent times, including the death of Hugo Chávez. His second-in-command, Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, is himself Venezuelan. Few diplomatic institutions understand Venezuela’s political and criminal ecosystems better.

Vatican officials also have long memories, having multiple U.S.-led interventions whose stated moral or legal justifications did not always align with perceived strategic motives, and whose consequences were often borne by ordinary people.