‘God’s Hotel’

“God’s Hotel: A Doctor, A Hospital, and a Pilgrimage to the Heart of Medicine” (Riverhead Books, $11.89), is the memoir of physician Victoria Sweet’s tenure at Laguna Honda, a long-term San Francisco hospital that for years was known as “the last almshouse in the country.”

“An elegant, though somber, riff on a 12th-century Romanesque monastery,” Dr. Sweet describes the place, and when she began working there in the early 1990s, patients, nearly always poor, could stay as long as they needed to.

There was a turret for a resident priest. There were open wards with a solarium at the end. There were nooks and crannies where the patients smoked, drank, played cards, and gambled. There was a greenhouse, a barnyard, and even an aviary.

Perhaps nothing captures the spirit of Laguna Honda more colorfully than when the AIDS hospice ward had its own much-beloved hen.

“[Medicine] intrigued me with its possibility of engaging with what Catholics call the last things: death, resurrection, heaven, hell and purgatory,” Sweet realized, and she tells many stories of the “miraculous” transformations, both physical and emotional, she observed in her patients over the years.

During her time at Laguna Honda, she learned Medieval Latin and earned a Ph.D. in the History of Medicine. In the process, she discovered much overlap between Hildegard of Bingen, the 12th-century German nun who wrote a practical medical text, and the mysteries of the body-soul connection she observed in her own contemporary practice.

Laguna Honda eventually became corporatized and is no more.

But “God’s Hotel” is a beacon, lighting new ways in which to think about treating our bodies, hearts, and souls — and reminding us that, in or out of the health care system, Christ is the Great Physician.

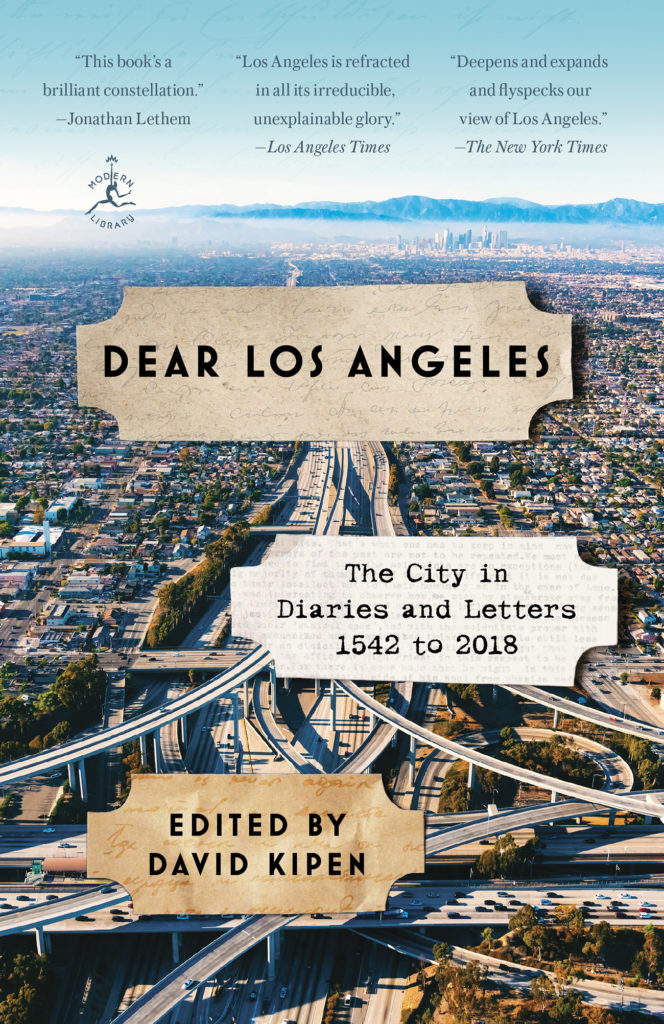

‘Dear Los Angeles’

“Dear Los Angeles: The City In Diaries and Letters, 1542 to 2018” (Modern Library, $23.65) is an unalloyed delight.

Rather than arrange the entries chronologically, author David Kipen, a native Angeleno, decided to start with Jan. 1 and work forward, juxtaposing passages from various time periods.

Thus, for any given day, you might read about a padre roaming on horseback sizing up prospective mission sites, an account of meeting Greta Garbo at a cocktail party and, say, on June 2, 1979, screenwriter Michael Palin’s evocative description of the city: “Low, flat, sprawling and laid-back — like a patient on a psychiatrist’s couch.”

One through-line emerges quickly: The more things change, the more they remain the same.

“[Southern Californians] never walk even the shortest distance.” Mormon soldier Henry Standage, June 24, 1847.

A second through-line is that the way any given person responds to LA has more to do with the person than with LA.

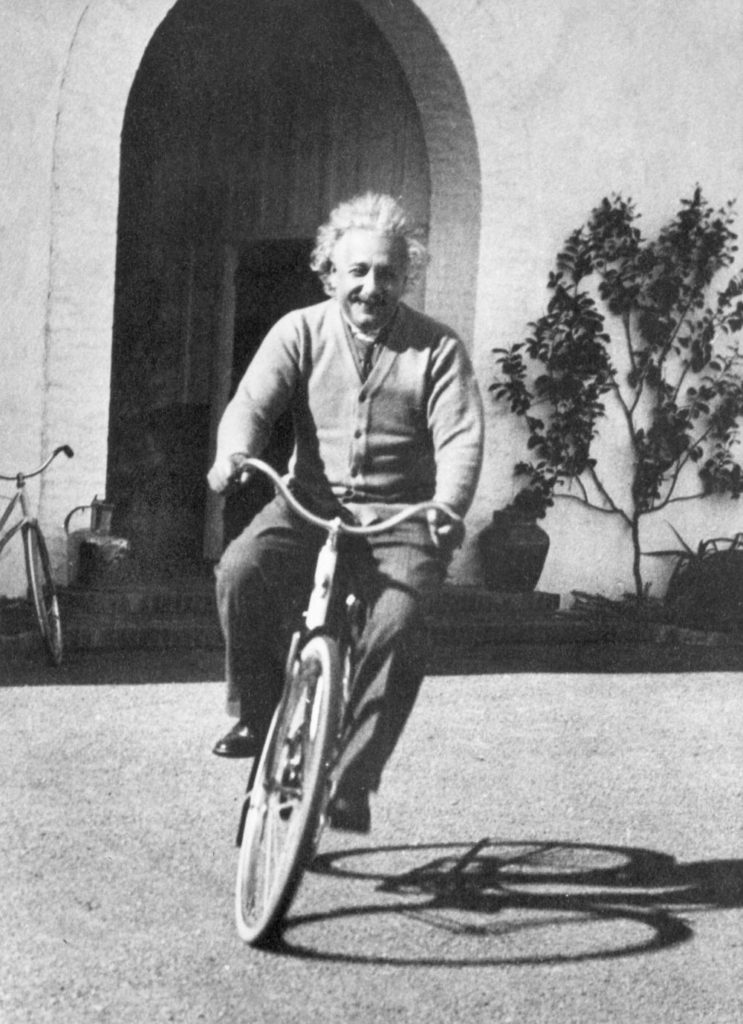

Albert Einstein, on Jan. 6, 1931: “Here in Pasadena, it is like Paradise. Always sunshine and clear air, gardens with palms and pepper trees and friendly people who smile at one [another] and ask for autographs.”

British composer Benjamin Britten on Aug. 19, 1942: “[Hollywood] is an extraordinary place — absolutely mad, and really horrible.”

The good, the bad, and the ugly in our beloved City of Angels: it’s all here.

Eric Knight, originator of “Lassie,” may have summed up LA best: “You wouldn’t believe that a place could be like this. The sham and the indescribable beauty.”

‘Where I Was From’

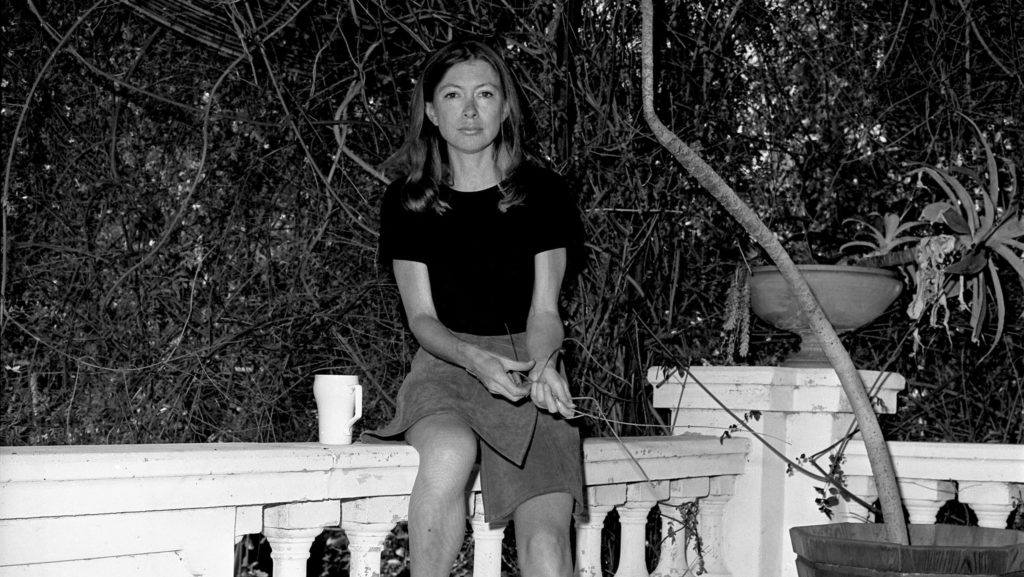

Joan Didion’s book “Where I Was From” (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, $13.92) is about leaving the place you’re from; learning as an adult that a lot of the family and local myths you were fed as a kid were highly varnished; and loving the place, to your bones, anyway.

Didion was heir to the “radical clarity” of her ancestors and the pioneer myths of California. Her people believed in getting through the Sierra before the snow fell, so as to avoid perishing in Donner Pass. They believed in getting things done, and bright futures, and passing on the heirloom silver flatware. If while driving her grandfather saw a rattlesnake, as part of “the Code of the West,” would stop, go into the brush, and kill it.

California is eternally golden and green. It’s camellia groves, “red Christmas-tree balls glittering in the firelight,” “the way the rivers crested and the way the tule fog obscured the levees.” It’s also Lakewood’s Spur Posse, the elite Bohemian Club of San Francisco, and the vapid paintings of Thomas Kinkade.

Didion eventually leaves Sacramento, where she was mostly raised, for New York City, then returns to a life in Malibu and Hollywood.

Over time she realizes that the “new people” at whom her family shudders had always been moving in. The new people had always sold “the future of the place we lived in to the highest bidder.” Even the Didions eventually let go of the family cemetery.

She ends with the death of her mother, who was so outwardly unsentimental that she often broke off phone conversations by hanging up mid-sentence.

Didion, usually likewise dry-eyed, allows herself this: “Who will look out for me now, who will remember me as I was, who will know what happens to me now, who will know where I was from.”