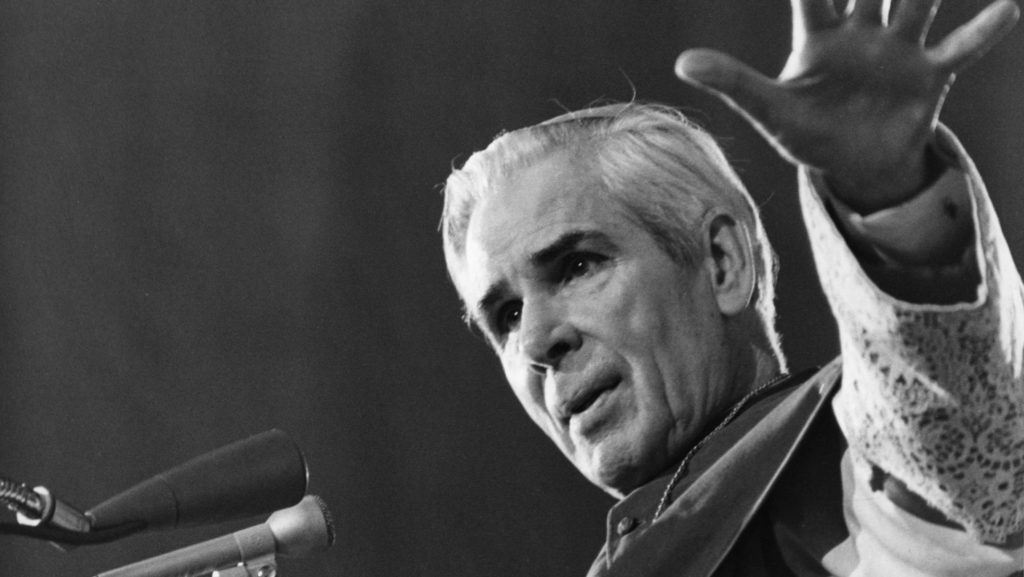

I have been hearing a lot from Venerable Fulton Sheen lately. On Sunday mornings, I drive my wife to work at the hospital and on my ride home the national Catholic radio station plays “reruns” of Sheen’s famous radio/television show, “Life is Worth Living.”

The rhetorical flourish Sheen had, his command of the English language, and an actor’s sense of timing make these programs, after decades of airings, still compelling. Rediscovering Sheen led me to do a little dip into his biography and another name from an even more distant past jumped out at me: Father Ronald Knox.

The name was familiar, but as I read this footnote in the Sheen bio, I realized this remarkable priest had been a precursor to the “pop culture” commentator priest that Sheen became. Like Sheen, Knox engaged in the popular culture of his own time, in early 20th-century England, and left behind a wealth of intellectual, theological, and popular cultural literature.

With so much clutter in our lives, it is easy to assume that not many people know who Sheen was, let alone that he had met a man who I am sure is even more obscure by American popular culture, and probably in most Catholic circles as well. But if people do not know who Knox was, they should.

He might have been one of the first popular culture priests. A man who used modern technology (radio) to evangelize, much like Sheen would later do, with deep thoughts, simple language and heavy doses of wry wit and humor.

Knox was Sheen before Sheen. Now, being a Catholic priest, a satirical essayist, a detective novel author, and a much-in-demand orator and homilist is a résumé that would give ChatGPT a run for its money. But Knox was so much more than that. In his “spare” time, he also translated the Latin Vulgate Bible.

Unlike Sheen, who was born into a devout Catholic family, Knox was born into Church of England royalty. His father was an Anglican priest when Knox entered this world in 1888 and later became the bishop of Manchester. His maternal grandfather was the bishop of Lahore when the British Empire was at its zenith in the subcontinent of India.

Imagine the seismic activity in his family when he converted to Catholicism and was ordained a priest in 1918. Knox’s ensuing years were filled with creative vigor that makes me feel puny when I look at my own output — and I do not have the excuse of most of my time being preoccupied with priestly duties. Like Sheen, Knox embraced the culture in which he lived and insisted on using even its potentially vulgar new inventions — TV for Sheen, radio for Knox — for a greater good.

In 1928, Knox produced a radio play called “Broadcasting the Barricades,” a fictional presentation of a full-blown revolution happening in the streets of London, which caused a bit of panic. A decade later, Orson Welles would be inspired by that event to create his own American version of mock documentary radio with his “War of the Worlds” broadcast, which resulted in people believing a Martian invasion was taking place. Knox’s purpose was not to frighten people or make a name for himself in radio, as was Welles’ intention, but rather to make some scathing commentary on British culture and society as it related to its variance from Catholic social teaching.

Knox also wrote detective novels, where he most certainly must have influenced his other main Catholic culture touchpoint, G.K. Chesterton, another Catholic pop culture-watcher who knew Knox, and who went on to some success with his own Father Brown mystery books. Knox had a “Ten Commandments” for detective fiction writers, with many of the tenets still holding true, like “not more than one secret room or passage is allowable” and “twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.”

The high motor in all of Knox’s work is to lead logically — whether through one of his detective novels or presentations on the radio — to God and his Church. This is what Sheen did, and it is what all good Catholic communicators do in our 21st century. There are many who try their hand at it, but few are as good as Sheen and Knox. Any priest or layperson who does try to emulate would be served well by Knox’s words: “The prime purpose of the Christian revelation was not to show men what they ought to do, but to give them the inspiration (if you dislike the word grace) to do it.”