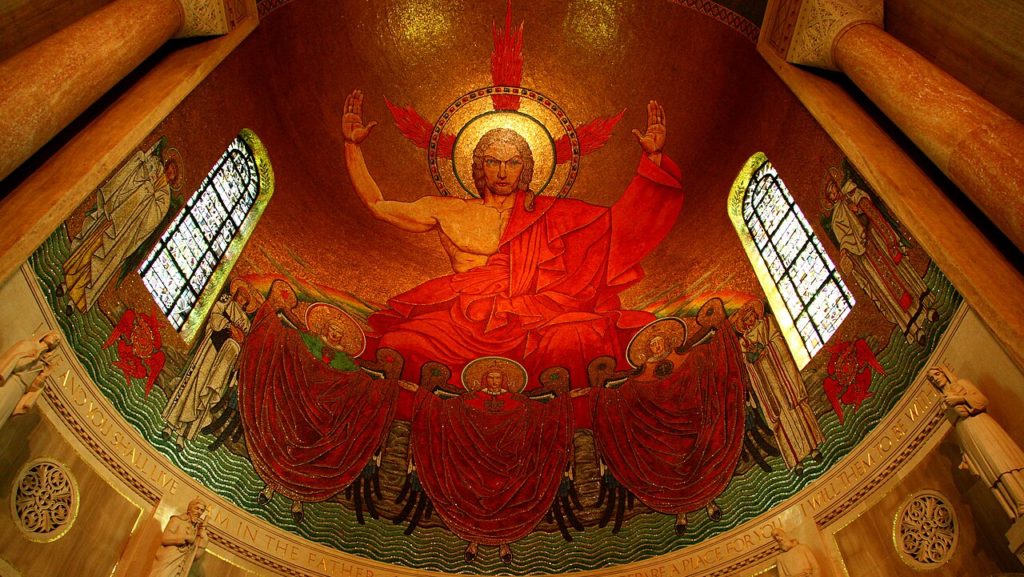

A colossal mosaic, “Christ in Majesty,” dominates the upper church at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. It’s a fierce portrayal of Jesus, his passion restrained only by the fixity of the Byzantine style.

The image resonates with me on many levels. Through my earliest years as a Christian, my formation was Calvinist, a Protestant tradition that emphasizes God’s sovereignty and judgment. “For the Lord is our judge, the Lord is our ruler, the Lord is our king,” said the Prophet Isaiah (33:22). And that’s how Jesus appears in the basilica.

The irony is that my Calvinist background prepared me to think of Christ that way, but not to see him that way — at least not in this life. The reformer John Calvin was a forceful opponent of devotional images, favoring bare church walls and bare crosses. He held that images, even images of Christ, presented a temptation to idolatry.

I am now four decades a Catholic. Yet every time I kneel beneath that overpowering image, I wonder whether it is my vestigial inner Calvinist that thrills at what I see — thrilling, nevertheless, as only a Catholic can thrill before a sacred image.

Some years ago, an essayist nicknamed this icon “Scary Jesus.” And it does seem to violate the canons of the Christian greeting-card industry.

Still, there is a more disquieting paradox at work in “Christ in Majesty.” The mosaic portrays Christ in judgment, as we might encounter him in the Book of Revelation. But doesn’t the same book portray Christ as a Lamb, so gentle that he can pass for dead (Revelation 5:6)? Didn’t the Word become flesh as a man who blessed the meek and didn’t fight back?

The icon forces us to confront a seeming contradiction: Our Lord as a just judge whose wrath is capable of consigning mortal sinners to hell; yet Our Lord is merciful and as meek as a barnyard animal in its infancy.

Some people have tried to reconcile these images by making them sequential. Jesus was soft and tender in his first coming, they say, but with the second coming, it’s “no more Mr. Nice Guy.” Well, this doesn’t work. First, because the Gospels show us that Jesus did indeed vent wrath on wicked men during his earthly life (e.g., Matthew 15:3–9, 21:12–13, 23:13–16), but also because the Book of Revelation shows Our Lord to be a Lamb to the very end, at the consummation of all human history (Revelation 21:22, 22:3).

So, which shall we worship? Which shall we contemplate? The Judge or the Lamb? Scary Jesus or Mr. Nice Guy?

The mystery of the Incarnation demands that we accept the perfect union of seemingly incompatible things: the finite contains the infinite; the eternal enters time; the sacrificial lamb presides on the Day of Wrath.

This is not a subtlety reserved for theologians. Dock workers and seamstresses have known it since the birthday of the Church. Even those who could not read knew the truth of Christ because of icons like “Christ in Majesty.”

What is scandalous about an icon is simply the scandal of the Incarnation, with all its paradoxes.