If you haven’t heard by now, Hollywood is at it again, offering viewers another serving of one of the staples of ancient Roman society: gladiators.

As Russell Crowe famously asked the crowds in the Coliseum: Are you not entertained?

“Gladiator II” certainly tries, with director Ridley Scott trying to recreate the magic of his award-winning box office hit from 2000. Irish actor Paul Mescal plays Lucius Verus, a young man seeking to continue the legacy of Crowe’s character, Maximus Decimus Meridius.

Although not as entertaining as its predecessor, “Gladiator II” offers a window into one of the most puzzling and outrageous vices of ancient Rome, begging the question: Were the Romans as obsessed with gladiators as Hollywood makes them to be?

The short answer is yes. Gladiators were celebrities, their pictures and names adorning everything from baby’s nursing bottles to dining room mosaics. Most gladiators were slaves, but free people (including women) would enlist, too, attracted by the lure of popularity and the chance of support from powerful patrons.

A slave gladiator could earn his freedom fighting, yet we know of several gladiators who preferred to remain enslaved to keep fighting in the arena. (Like today’s elite athletes, gladiators found it hard to retire after many years in the spotlight.)

Despite their popularity, their status in Rome was controversial. The Christian writer Tertullian writes: “The art they glorify, the artist they debase.” A gladiator used his body to entertain others. The Roman mentality considered this slave-like and demeaning, but it did not stop the emperor Commodus, the villain of the first “Gladiator,” from fighting more than 700 times in gladiatorial contests!

“Gladiator II” takes the spectacle of the arena to the next level, with a gladiator riding a rhino and a naval battle in the flooded Coliseum featuring famished sharks roaming the waters — scenes that are not that far removed from historical reality. While we don’t know of anybody riding a rhino, their presence in the games is well attested. And yes, the Coliseum was flooded to stage naval battles, sometimes featuring marine animals (but not sharks).

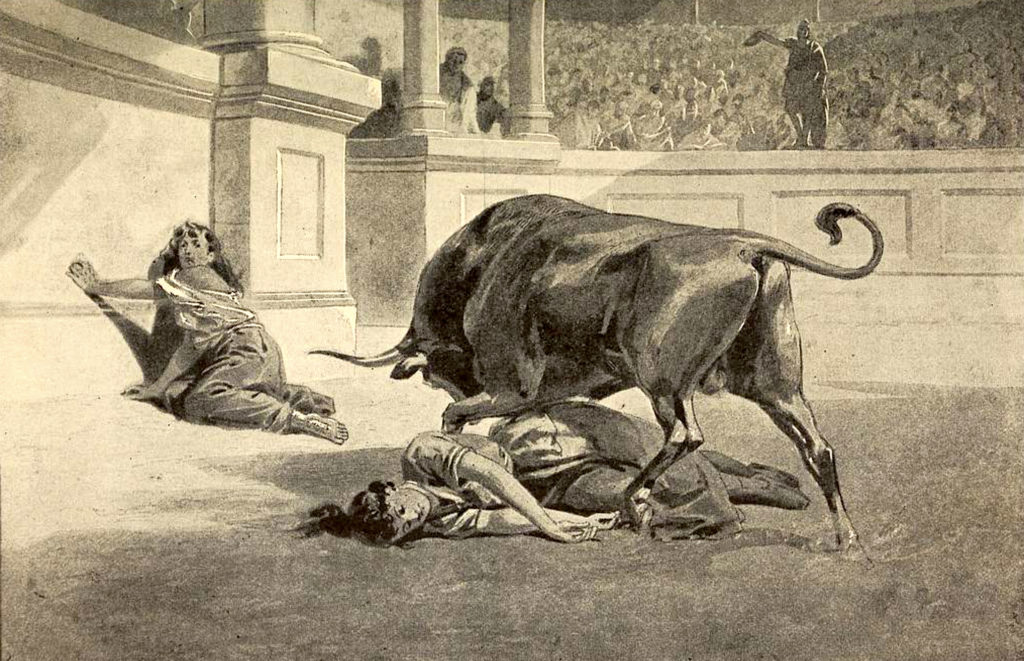

The more serious inaccuracies have to do with the distinctions between the different combat shows. A typical day at the games began in the morning with hunts (venationes), during which trained specialists (bestiarii) fought wild animals. Then came the midday show, mostly featuring the punishment of convicts: criminals (sometimes including Christians) or prisoners of war, who were often executed by being fed to wild animals or forced to fight one another to death in staged battles.

But all of this was the ancient equivalent of tailgating: the real show was the afternoon gladiator fights, fought only one-on-one and with special rules.

Despite their lower status, Romans admired gladiators for their ability to face death fearlessly. A defeated gladiator would kneel, grab his opponent’s leg, and stretch his neck to receive the final blow.

The great Roman orator Cicero writes: “What even mediocre gladiator ever groans, ever alters the expression on his face? And which of them, even when he does succumb, ever contracts his neck when ordered to receive the blow?” Gladiators didn’t flinch.

The public execution and humiliation of convicts was meant to inspire terror in those who opposed the emperor’s power. The spectacle of Christians accepting death for their faith, often displaying the same bravery as gladiators, deeply impressed the Romans. The “Passion of Perpetua and Felicity” from the third century recounts how Perpetua, after being wounded, requested to be taken back to the arena to receive the final blow like a proper gladiator. This might be one of the reasons the persecution of Christians spectacularly failed to dissuade new conversions.

In its soppy Hollywood ending, Lucius waxes about “a home worth fighting for.” As in the first “Gladiator,” the sequel casts its conflict as being between good guys and bad guys, republic vs. empire, tyranny vs. democracy. When it comes to the period of history in which the movies are set (third century), nothing could be further from the truth.

Love for freedom was a key value for Romans (quite the paradox for a slave-owning society), and one they have bequeathed the Western world. But the Roman republic, with its system of elected magistrates, was eminently unsuited to administer an empire the size of Rome.

After about 60 years of almost uninterrupted civil war, Augustus turned Rome into a monarchy. There was an attempt to return to the republican system after the death of Caligula (A.D. 41), but by the time of “Gladiator”-era emperors like Marcus Aurelius and Caracalla, no one would have believed a return to the Republic to be feasible.

Bad emperors like Caracalla and Nero were loathed by the senators, but very popular with the plebeians, or common people. Thanks to their games and donations, the plebeians regarded them as the champions of the oppressed. Challenges to the emperors tended to come from high-ranking generals and members of the senatorial elite, not the plebs.

One thing that sets “Gladiator II” apart from the original is its citations of ancient literature. In Virgil’s famous poem “The Aeneid,” the titular hero begs the sibyl, a prophetess of the god Apollo, to let him descend to the underworld. She replies: “The gates of hell are open night and day; | Smooth the descent, and easy is the way: | But to return, and view the cheerful skies, | In this the task and mighty labor lies.’

Probably the meaning is that, in the world of gladiators, dying is easy, and staying outside of the underworld is the real task. Or maybe the idea is that Lucius Verus is in some way a reincarnation of his father Maximus, returned from the dead to get revenge on a corrupt emperor.