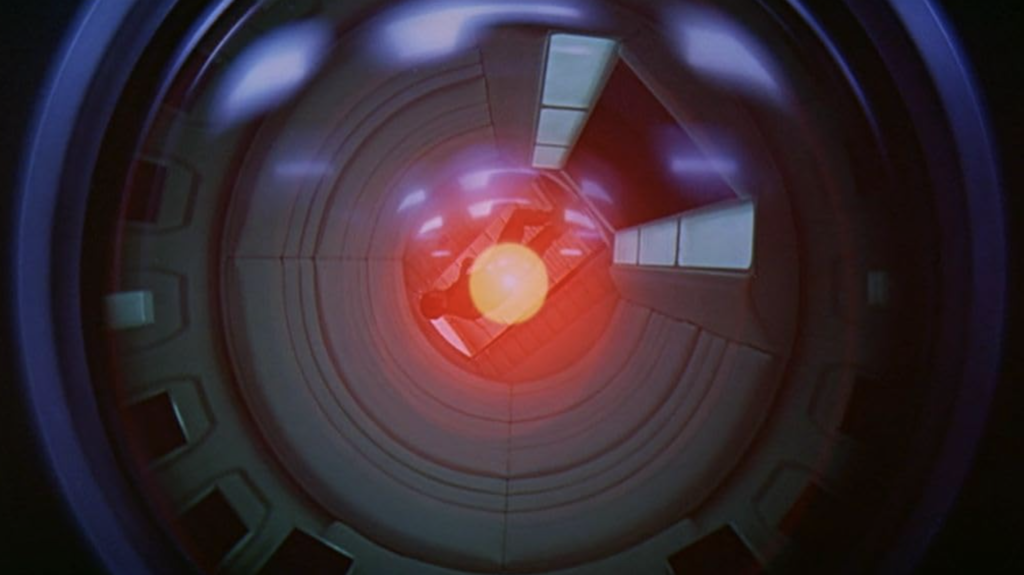

Remember HAL? For those whose memories may not go back that far, HAL (Heuristically Programmed Algorithmic Computer) was the murderous artificial intelligence (AI) machine in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Based on stories by Arthur C. Clarke, the movie contains a segment in which HAL deliberately causes the deaths of several astronauts in outer space.

HAL’s villainy was fictitious, but 56 years later it’s a different story. Artificial intelligence has moved ahead by leaps and bounds, so that now, although no such machine is known to be exhibiting homicidal tendencies, the potential dangers of artificial intelligence are causing serious people to sound warning bells.

Pope Francis is one. Addressing an artificial intelligence session of G7, an international body involving the U.S. and six other highly developed liberal democracies, the pope called AI an “extremely powerful tool” that “generates excitement for the possibilities it offers” but also “gives rise to fear for the consequences it foreshadows.”

You can’t say we haven’t been warned. The G7 session itself was a sign of growing concern about AI. And threats posed to human well-being by science and technology run amuck has been a literary theme for more than two centuries.

One of the first to address the topic was Mary Shelley’s 1818 “Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus,” about a scientist who assembles a humanoid monster and then must deal with the dilemma of what to do with it. (Shelley’s story bears little resemblance to all those Frankenstein movies.) Later came H.G. Wells’s 1896 “The Island of Doctor Moreau,” about a mad scientist who creates human-animal hybrids.

Fiction focused on the harmful potential of science and technology thrived in the 20th century. Notable examples include Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel “Brave New World,” with its nightmare vision of test-tube babies mass produced in laboratory factories — something now happening via in vitro fertilization — and Karel Capek’s 1936 “War With the Newts,” about the bad things that will come from training newts to be as rapacious and bloodthirsty as human beings. And technology-enforced totalitarianism famously provides the setting for George Orwell’s “1984,” which marked its 75th anniversary last year.

The dangers associated with technology are not fiction. Back in 1947, with Nazi death camps, the firebombing of Dresden, and the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki fresh in mind, theologian Romano Guardini delivered lectures that became a book called “The End of the Modern World.”

The heart of it was that at a time when human beings were acquiring ever more power over the world, “man is removing himself farther and farther from the norms which spring from the truth of being and from the demands of goodness and holiness. … He must regain his right relation to the truth of things, to the demands of his own deepest self and finally to God. Otherwise he becomes the victim of his own power.”

In his 1979 encyclical Redemptor Hominis (“The Redeemer of Man”), St. Pope John Paul II warned that human beings themselves are “subject to manipulation” by the products of our own technology. And in his address to the G7, Francis spoke of a diminishing appreciation of human dignity, declaring it to be what is “most at risk in the implementation and development of these [AI] systems.”

More and more people seem to be waking up to the problem that unconstrained development of AI could pose. European governments have been taking appropriate action to control AI, but the U.S. has dragged its feet. Let’s hope we catch on before HAL does.